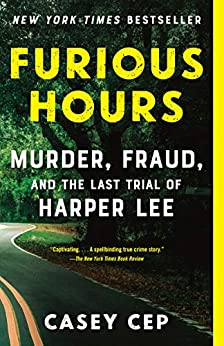

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Casey Cep

Read between

June 5 - July 12, 2020

There were only twelve thousand people in the whole of Coosa County at the time, and enough pine trees that a boy playing Tarzan could practically swing from one end of it to the other without touching the ground. What little crime there was ran to bigamy, bastardy, hoboing, failing to honor the Sabbath, and using vulgar language in front of women.

Shelling was a peaceful, mindless task, good for gossip if you had company and contemplation if you did not.

Most early anthropologists and historians shared the biases of the culture at large, leaving them uninterested in or even antagonistic to African spirituality in general and voodoo in particular.

Mouths don’t empty themselves unless the ears are sympathetic and knowing.”

The healing aspects of voodoo were essential for a population routinely unable to access health care because of their race, socioeconomic standing, or distance from doctors and hospitals;

Plenty of good Christians in Coosa County shook out their pillows at night and scrubbed their steps in the morning to fend off spirits and spells, warned their children that the hoodoo man would get them if they stayed out too late, and told their spouses that they would lay a trick on them if they did not stop drinking or lying or lying about drinking.

Supernatural explanations flourish where law and order fails, which is why, as time passed and more people died, the stories about the Reverend grew stronger, stranger, and, if possible, more sinister.

Racial bias was ubiquitous in the insurance industry. African American policyholders were routinely required to pay more money for less valuable coverage, refused consolidation offers for discounts on multiple policies, forced to pay premiums exceeding the value of the payout, and denied benefits based on capricious claims of lapsed coverage.

Some companies maintained dual rates for white and black clients, based on separate mortality tables that were used to justify charging nonwhites more than whites for the same policies; others maintained dual plans, using one mortality table but offering two levels of insurance, and paying agents the full commission only when minority clients bought substandard policies. Some companies simply refused to insure black lives at all.

As a rule, most southern towns are allergic to authority and resent any federal presence that isn’t a post office.

At one point during the service, a folding chair slid down from where it had been propped against a wall, clanging loudly against the ground and causing all the lawmen to reach for their guns. But no one was shot at the funeral of the man who was shot at a funeral.

But when he added that the Devil couldn’t take the Reverend from God either, the chorus quieted, and when he said that Maxwell would be coming back to judge those who had judged him, people all over the chapel shook their heads in disapproval or alarm, and one man said audibly, “I hope to hell not.”

Between her father and her sister, Nelle had spent years listening to cases in the Monroe County Courthouse. Movies might have cost a dime, but trials were free.

“I am more of a rewriter than a writer,” Lee said, and explained that everything she wrote, she wrote at least three times. She claimed that while there could be “no substitute for the love of language, for the beauty of an English sentence,” there was also “no substitute for struggling, if a struggle is needed.”

It was, you might say, rich: poor, penniless Harper Lee, who had been living without hot water, writing on a makeshift desk, walking to avoid paying bus fare, begging her agents for more money from her advance to cover expenses, flat-sitting for Truman Capote and Jack Dunphy to save on rent, and surviving on peanut butter and whatever meals she could filch from friends—that same Harper Lee was suddenly so wealthy that she couldn’t work.

Years later, she would inscribe a copy of To Kill a Mockingbird to Morris Dees, the co-founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center—who, she wrote, would “be remembered as the one who spoke

when good men remained silent, and the one who acted when good men did nothing.”

“More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones.”

reporters love trials because they “are transfixed by a process in which the person being asked a question actually has to answer it.

Harper Lee returned over and over again to the town where she was born, and Big Tom never really left; both of them were deeply loyal to the South, even when it disappointed them or disapproved of them.

There was the poetry of Blake, Wordsworth, and Thomas Hardy, together with the contemporary American writers she admired—among them, Mary McCarthy, John Updike, Peter De Vries, John Cheever, and Flannery O’Connor—plus histories, crime stories, law books, and her five favorite novels: Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh, Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, Richard Hughes’s High Wind in Jamaica, and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

However good a lawyer he was, she understood right away that no matter whom he was representing, he was first and foremost representing himself.

History isn’t what happened but what gets written down, and the various sources that make up the archival record generally overlooked the lives of poor black southerners.

As Kierkegaard observed, we live forward but comprehend backward;