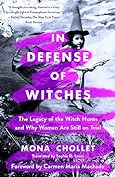

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Mona Chollet

Read between

August 19 - August 19, 2025

There is no “joining” WITCH. If you are a woman and dare to look within yourself, you are a Witch.

Every possible decision modern women make or role they occupy, outside of the most rigorous and regressive, can be tied back to the very symptoms of witchcraft: refusal of motherhood, rejection of marriage, ignoring traditional beauty standards, bodily and sexual autonomy, homosexuality, aging, anger, even a general sense of self-determination.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a more enduring and potent archetype than the witch; she has served as a shorthand for women’s power and potential

By wiping out entire families, by inducing a reign of terror and by pitilessly repressing certain behaviors and practices that had come to be seen as unacceptable, the witch-hunts contributed to shaping the world we live in now.

Executions were still taking place at the end of the eighteenth century—for example, that of Anna Göldi, who was beheaded at Glarus, in Switzerland, in 1782. As Guy Bechtel writes, the witch “was a victim of the Moderns, not the Ancients.”

The secular court judges revealed themselves to be “more cruel and more fanatical than Rome”7 when it came to witchcraft.

The witch-hunts demonstrate, first, the stubborn tendency of all societies to find a scapegoat for their misfortunes and to lock themselves into a spiral of irrationality, cut off from all reasonable challenge, until the accumulation of hate-filled discourse and obsessional hostility justify a turn to physical violence, perceived as the legitimate defense of a beleaguered society.

The demonization of women as witches had much in common with anti-Semitism.

Terms such as witches’ “sabbath” and their “synagogue” were used; like Jews, witches were suspected of conspiring to destroy Christianity and both groups were depicted with hooked noses.

The political enemies of certain high-born figures would occasionally denounce the latter’s daughters or wives as witches; this was easier than attacking their enemies directly.

The men of their families rarely attempted to support them—sometimes even adding their voices to those of the accusers. For some, this reticence can be explained by fear: men accused of witchcraft were for the most part accused due to their intimacy with “witches.”

A woman must have a master, even if he’s the man who kidnapped and assaulted her when she was twelve.