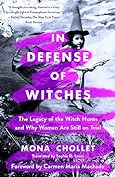

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Mona Chollet

Read between

June 26 - July 5, 2022

Every possible decision modern women make or role they occupy, outside of the most rigorous and regressive, can be tied back to the very symptoms of witchcraft: refusal of motherhood, rejection of marriage, ignoring traditional beauty standards, bodily and sexual autonomy, homosexuality, aging, anger, even a general sense of self-determination.

The work of two inquisitors, Heinrich Kramer (or Henricus Institor) from Alsace and Jakob Sprenger from Basel, the Malleus Maleficarum was published in 1487 and has been compared to Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

men accused of witchcraft were for the most part accused due to their intimacy with “witches.” Others took advantage of the climate of general suspicion “to free themselves from unwanted wives and lovers, or to blunt the revenge of women they had raped or seduced,” as Silvia Federici explains; in her analysis, the “years of propaganda and terror sowed among men the seeds of a deep psychological alienation from women.”

The public staging of the tortures, a powerful source of terror and collective discipline, induced all women to be discreet, docile and submissive—not to make any waves. What’s more, one way or another, they were compelled to assume the conviction that they were the incarnation of evil; they were forcibly persuaded of their own guilt and fundamental wickedness.

The married woman’s social debarment would be formalized in France with the civil law of 1804. The witch-hunts had by then fulfilled their function: there was no further need to burn women alleged to be witches; now, the law “enabled the curtailment of all women’s independence.”

Although occasionally freer in her behavior and her speech, as soon as she turned into a mouth not worth feeding, the post-menopausal woman became a millstone round the neck of her community.

Modern medicine, in particular, was built on this model, and the witch-hunts enabled the official doctors of the period to eliminate competition from female healers—despite their being broadly more competent than the doctors.

when you want to channel someone else’s potency, an encounter with an image or a thought of theirs can be enough to produce spectacular effects.

In contrast, the conjugal apostates have always cultivated a critical distance, sometimes even wholesale defiance in relation to these roles. And they are creative women, who tend to read a lot and lead a rich life of the mind: “They live beyond the range of the male gaze, beyond that of most others, for their solitude is populated with works of art and with people, living and dead, dear as well as unknown, encounters with whom—whether in flesh and blood or in thought, through their oeuvres—form the foundations to the women’s sense of identity.”40 These women consider themselves individuals,

...more

“Life” does not inspire them to action except when it comes to wrecking women’s lives. A pro-birth policy is about wielding power, not about care for humanity.

Resistance to having children may be one way to hold society responsible for its lapses and failures, to refuse to pass the buck,

There is room for every view, it seems to me. I only struggle to understand why the one I subscribe to is so poorly accepted and why an immovable consensus persists around the idea that, for everyone, to succeed in life implies having offspring.

each person’s path through life is a succession of dominoes knocked onward, and each knock leaves its mark,

Adrienne Rich also wrote that “The ‘childless woman’ and the ‘mother’ are a false polarity, which has served the institutions both of motherhood and heterosexuality. There are no such simple categories.”

A man is called “mister” from the age of eighteen or earlier until the end of his life; for a woman, there must always come this moment when, in all innocence, people encountered in her daily life join forces to tell her that she no longer appears young. I remember being upset and even offended by my first “madames.”

“Men don’t age better than women, they’re just allowed to age.”19 The late, great Carrie Fisher retweeted this when, in 2015, viewers of the latest episode in the Star Wars saga were scandalized to see that Leia was no longer the intergalactic, bikini-clad brunette bombshell of forty years ago (some even tried to ask for their money back).

The speculum was invented in the 1840s by James Marion Sims, a doctor from Alabama who carried out numerous experiments on slaves; he forced one of them, called Anarcha, to go through thirty-odd operations without anaesthesia. “Racism and sexism is [sic] baked into the innocuous speculum itself—think of that next time you’re in the stirrups,” suggests Sarah Barmak, the Canadian author of Closer, about the ways women are now reclaiming sex for themselves.

Matilda Joslyn Gage’s analysis (as early as 1893) seems altogether more plausible: During the witchcraft period the minds of people were trained in a single direction. The chief lesson of the church that betrayal of friends was necessary to one’s own salvation created an intense selfishness. All humanitarian feeling was lost in the effort to secure heaven at the expense of others, even those most closely bound by ties of nature and affection. Mercy, tenderness, compassion were all obliterated. Truthfulness escaped from the Christian world; fear, sorrow and cruelty reigned pre-eminent.

In 2017, black artist Harmonia Rosales reinterpreted Michelangelo’s fresco for the Sistine Chapel, The Creation of Adam. She replaced Adam and God, both white men in Michelangelo’s depiction, with two black women, and she called her piece The Creation of God: a way of proclaiming that the emperor has no clothes.