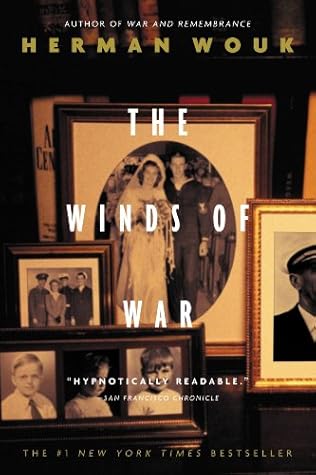

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Herman Wouk

Read between

May 28, 2012 - February 19, 2021

(from WORLD EMPIRE LOST)

The False Legend

A serious military discussion has to start by clearing away the fairy tales.

The whole problem in the summer of 1940 was to force a decision across a sea barrier. In a set-piece invasion campaign, therefore, the British held the crucial advantage.

Germany and England had about a thousand fighter planes when the contest began. Germany’s bomber command was larger than England’s, but the English bombers, at least the newer ones, were heavier, longer-ranged, and more powerfully armed.

British Advantages

Because of our fighter planes’ short range, we could reach only the southeast corner of England. The Luftwaffe was like a tethered falcon, with London at the far end of the tether. The rest of the United Kingdom was fairly safe from air attack, because unescorted bombers ran a high risk of annihilation. The Royal Air Force could retire beyond range at will for rest and repair; and far beyond the firing line could keep fresh reserves and could rush the building of new planes.

Fighter pilot teams should be free to roam the air space, spot the enemy, and strike first. Göring could never grasp this elementary point, though his fighter aces kept urging it on him. As our bomber losses climbed, he insisted more and more violently that the fighters should nursemaid the bombers, almost wingtip to wingtip. This seriously depressed pilot morale, already strained by prolonged combat and the death of many comrades.

Churchill himself—and he is not interested in praising the German effort—states that in September the battle tilted against his fighter command.

The Purpose of “Eagle Attack”

Hitler and England

No world-historical figure, when entering the scene, ever made his aims and his program clearer. By comparison, Alexander, Charles XII, and Napoleon were improvisers, moving where chance took them. In Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote in bombastic street-agitator language what he intended to do upon attaining power; and in the twelve years of his reign he did it. He wrote that the heart of German policy was to seize territory from Russia. That effort was the fulcrum of the Second World War, the sole goal of German arms. He also wrote that before this could be attempted, our traditional enemy France

...more

In discussing England, Hitler in Mein Kampf praises the valor of the race, its historical acumen, and its excellent imperial administration. Germany’s grand aim, he says, must be a Nordic racial alliance in which England maintains its sea empire, while Germany as its equal partner takes first place on the continent and acquires new soil in the east.

The Air Battle

Hermann Göring was a complicated mixture of good and bad qualities. He was clever and decisive, and before he sank into stuporous luxury, he had the brutality to enforce the hardest decisions. All this was to the good. But his vanity shut his mind to reason, and his obstinacy and greed crippled aircraft design and production. Until Speer came into the picture, the Luftwaffe was worse hit by bad management and supply on the ground than by any enemy in the air, including the Royal Air Force in 1940. Göring vetoed excellent designs for heavy bombers, and built a short-range air force as a ground

...more

In fact, from start to finish Hitler soberly and coolly—though with self-defeating amateurish mistakes in combat situations—followed out the political goals laid down in Mein Kampf, step by step. He yearned to come to terms with England. No victorious conqueror ever tried harder to make peace. The failure to achieve this peace through the Eagle attack was of course a disappointment. It meant that our rear remained open to nuisance attack from England while we launched the main war in the east.

The Final Tragedy

He had in any case an unreasonable attitude toward the Jewish people.

A Germany allied with England—even with a benevolently neutral England—would never have drifted into those excesses.

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE:

Roon’s far-fetched thesis that Winston Churchill’s stubbornness caused the murder of the European Jews may be the low point in all this literature of self-extenuation.

Göring tried to get daylight mastery of the air, the two fighter commands slugged it out, and he failed; then he tried to bomb the civilian population into quitting, first by day and then by night, and failed. The British fighter pilots turned the much larger Luftwaffe back, and saved the world from the Germans.

There was no clear-cut moment of victory for the British. They really won when Sea Lion was called off, but this Hitler backdown was a secret. The Luftwaffe kept up heavy night raids on the cities, and this with the U-boat sinkings made the outlook for England darker and darker until Hitler attacked the Soviet Union. But the Luftwaffe never recovered from the Battle of Britain. This was one reason why the Germans failed to take Moscow in 1941. The blitzkrieg ran out of blitz in Russia because it had dropped too much of it on the fields of Kent and Surrey, and in the streets of London.—V.H.

31

This was the end of a tedious week-long journey for Pug via Zurich, Madrid, Lisbon, and Dublin. It had begun with the arrival in Berlin of a wax-sealed envelope in the pouch from Washington, hand-addressed in red ink: Top Secret—Captain Victor Henry only. Inside he had found a sealed letter from the White House.

Dear Pug:

The British are secretly reporting to us a big success in their air battle with something called “RDF.” How about going there now for a look, as we discussed?

FDR

He had not walked the deck of a ship now in the line of duty for more than four years, and this shore-bound status appeared to be hardening.

So far the few English raiders had hugged maximum altitude, but the Germans seemed to think of everything. This gigantic drab iron growth, towering over the playing children and elderly strollers in the pretty Tiergarten, seemed to Victor Henry to epitomize the Nazi regime.

He wrote letters to Rhoda, Warren, and Byron, and went to sleep thinking of his wife, and thinking, too, that in London he would probably see Pamela Tudsbury.

And so he had departed from Berlin.

“We do get some air raid warnings, but so far the Germans haven’t dropped anything on London. You see contrails once in a while, then you know the fighters are mixing it up close by. Otherwise you just listen to the BBC for the knockdown reports. Damn strange war, a sort of airplane numbers game.”

He found Pamela Tudsbury’s number in the telephone book and called her. A different girl answered, with a charming voice that became more charming when Victor Henry identified himself. Pamela was a WAAF now, she told him, working at a headquarters outside London. She gave him another number to call. He tried it, and there Pamela was.

He dined alone in a small restaurant, on good red roast beef such as one could only dream of in Berlin. The apartment was dark and silent when he returned. He went to bed after listening to the news. The claimed box score for the day was now a hundred thirty German planes down, forty-nine British. Could it be true?

“Do you think Hitler’s crazy?” Henry said. Tillet chewed at his pipe, eyes on the road. “He’s a split personality. Half the time he’s a reasonable, astute politician. When he’s beyond his depth he gets mystical, pompous, and silly. He informed me that the English Channel was just another river obstacle, and if he wanted to cross, why, the Luftwaffe would simply operate as artillery, and the navy as engineers. Childish. All in all, I rather like the fellow. There’s an odd pathos about him. He seems sincere, and lonely. Of course, there’s nothing for it now but to finish him off.—Hullo, we

...more

Victor Henry’s first glimpse of British radar scopes at Ventnor, in a small stuffy room lit by one red light and foul with smoke, was a deep shock. He listened intently to the talk of the pale, slender man in gray tweed called Dr. Cantwell, a civilian scientist, as they inspected the scopes. But the sharp green pips were news enough. The British were miles ahead of the United States. They had mastered techniques that American experts had told him were twenty years off. The RAF could measure the range and bearing of a ship down to a hundred yards or less, and read the result off a scope at

...more

Churchill put on half-moon glasses, took up a paper and glanced at it, then peered over the rims at Henry. “Your post is naval attaché in Berlin. Your President has sent you here to have a look at our RDF, a subject in which you have special knowledge. He reposes much confidence in your judgment.” Churchill said this with a faint sarcastic note suggesting that he knew Pug was one more pair of eyes sent by Roosevelt to see how the British were taking the German air onslaught; also, that he did not mind the scrutiny a bit.

“Well, then, I suggest you report to your President that we simple British have somehow got hold of something he can use.” “I’ve done so.” “Good! Now have a look at these.”

The colored curves and columns of the charts showed destroyer and merchant ship losses, the rate of new construction, the increase of Nazi-held European coastline, and the rising graph of U-boat sinkings. It was an alarming picture.

Churchill said that the fifty old destroyers were the only warships that he would ever ask of the President. His own new construction would fill the gap by March. It was a question of holding open the convoy lines and beating off invasion during these next eight months.

“Here’s that bad man’s invasion fleet. Landing craft department,” Churchill went on, scooping up and handing him a sheaf of photographs showing various oddly shaped boats, some viewed in clusters from the air, some photographed close on. “A raggle-taggle he’s still scraping together. Mostly the prahms they use in inland waterways. Such cockleshells will ease the task of drowning Germans, as we devoutly hope to do to the lot of them. I should like you to tell your President that now is the time to get to work on landing craft. We shall have to go back to France and we shall need a lot of these.

Churchill stared back, his broad lower lip thrust out. “Oh, I assure you we shall do it. Bomber Command is growing by leaps and bounds. We shall one day bomb them till the rubble jumps, and invasion will administer the coup de grace. But we shall need those landing craft.”

“Tillet is very good. His views on Gallipoli I regard as slightly unsound, since he makes me out at once a Cyrano, a jackass, and a poltroon.” He held out his hand. “I suppose you’ve seen a bit of Hitler. What do you think of him?” “Very able, unfortunately.” “He is a most wicked man. The German badly wants tradition and authority, or this black face out of the forest appears. Had we restored the Hohenzollerns in 1919, Hitler might still be a ragged tramp, muttering to himself in a squalid Vienna doss house. Now, alas, we must be at considerable trouble to destroy him. And we shall.”

Churchill swept his arms wide, and Victor Henry saw in his mind’s eye thousands of landing craft crawling toward a beach in a gray dawn. “Thank you, Mr. Prime Minister.”

32

The British were beginning to turn out tanks, planes, guns, and ships as never before. They now claimed to be making airplanes faster than the Germans were knocking them down. The problem was getting to be fighter pilots. If the figures given him were true, they had started with somewhat more than a thousand seasoned men. Combat attrition was taking a steep toll, and to send green replacements into the skies was fruitless. They could kill no Germans and the Germans could kill them. England had to sweat out 1940 with the fighter pilots on hand. But how fast was the Luftwaffe losing its own

...more

Pug gathered that almost half the pilots that had started the war were dead.

“Are you sure?” “Yes. He may have parachuted, but his plane dove into the sea. Two of his squadron mates reported it. He’s down.”

It became a settled thing among the Americans that Pug Henry had found himself a young WAAF.