More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

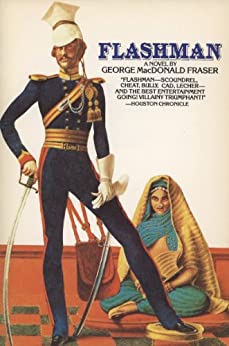

So I can look at the picture above my desk, of the young officer in Cardigan’s Hussars; tall, masterful, and roughly handsome I was in those days (even Hughes allowed that I was big and strong, and had considerable powers of being pleasant), and say that it is the portrait of a scoundrel, a liar, a cheat, a thief, a coward—and, oh yes, a toady.

So I rode to town, puzzling over how my father would take the good news. He was an odd fish, the guv’nor, and he and I had always been wary of each other. He was a nabob’s grandson, you see, old Jack Flashman having made a fortune in America out of slaves and rum, and piracy, too, I shouldn’t wonder, and buying the place in Leicestershire where we have lived ever since.

At this time there was a great unrest throughout Britain, in the industrial areas, which meant very little to me, and indeed I’ve never troubled to read up the particulars of it. The working people were in a state of agitation, and one heard of riots in the mill towns, and of weavers smashing looms, and Chartists7 being arrested, but we younger fellows paid it no heed.

all I gathered was that the poor folk were mutinous and wanted to do less work for more money, and the factory owners were damned if they’d let them. There may have been more to it than this, but I doubt it, and no one has ever convinced me that it was anything but a war between the two.

You may wonder why I took pains to ingratiate myself with these puritan boors, and the answer is that I have always made a point of being civil to anyone who might ever be of use to me.

Let me say that when I talk of disasters I speak with authority. I have served at Balaclava, Cawnpore, and Little Big Horn. Name the biggest born fools who wore uniform in the nineteenth century—Cardigan, Sale, Custer, Raglan, Lucan—I knew them all. Think of all the conceivable misfortunes that can arise from combinations of folly, cowardice, and sheer bad luck, and I’ll give you chapter and verse. But I still state unhesitatingly, that for pure, vacillating stupidity, for superb incompetence to command, for ignorance combined with bad judgement—in short, for the true talent for

...more

I have observed, in the course of a dishonest life, that when a rogue is outlining a treacherous plan, he works harder to convince himself than to move his hearers.

It was a common custom at that time, in the more romantic females, to see their soldier husbands and sweethearts as Greek heroes, instead of the whoremongering, drunken clowns most of them were. However, the Greek heroes were probably no better, so it was not so far off the mark.

Oh, lor’, I thought, if only you knew, you romantic little woman, thinking I’m a modern Horatius. (I made a point of studying Macaulay’s ‘Lays’ later, and she wasn’t too far off, really; only the chap I resembled was False Sextus, a man after my own heart).

Flash Harry!

This myth called bravery, which is half-panic, half-lunacy (in my case, all panic), pays for all; in England you can’t be a hero and bad.

We shook hands, and he drove off. I never spoke to him again. Years later, though, I told the American general, Robert Lee, of the incident, and he said Wellington was right—I had received the highest honour any soldier could hope for. But it wasn’t the medal; for Lee’s money it was Wellington’s hand. Neither, I may point out, had any intrinsic value.

1. Lord Brougham’s speech in May, 1839, “lashed the Queen…with unsparing severity” (Greville) and caused great controversy.