More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Chaos was a TV camera in your face, not enough ambulances, not enough officers, and no plan for how to react when the world as you knew it went to pieces.

Later, he would remember other sights that he didn’t have time to register right away: the heating duct covers that had been pried loose so that students could hide in the crawl space; the shoes left behind by kids who literally ran out of them; the eerie prescience of crime-scene outlines on the floor outside the biology classrooms, where students had been tracing their own bodies on butcher paper for an assignment.

It was why these schools, post-9/11, had teachers wearing ID all the time and doors locked during the day—the enemy was always supposed to be an outsider, not the kid who was sitting right next to you.

There were two ways to be happy: improve your reality, or lower your expectations.

Lacy knew you could be solidly pro-choice but unwilling or unable to make that decision for yourself—that’s exactly where the choice part kicked in.

But then again, maybe bad things happen because it’s the only way we can keep remembering what good is supposed to look like.

when he and his wife, Selena, stood in front of the television set watching CNN’s coverage of the school shooting at Sterling High. “It’s like Columbine,” Selena said. “In our backyard.”

Lacy smiled widely at her son. “One day, Peter, everyone’s going to know your name.”

His new eyeglasses were light as a feather and had special lenses that wouldn’t scratch even if he fell down and they went flying across a sandbox.

If you spent your life concentrating on what everyone else thought of you, would you forget who you really were? What if the face you showed the world turned out to be a mask . . . with nothing beneath it?

A gun was nothing, really, without a person behind it.

If you gave someone your heart and they died, did they take it with them? Did you spend the rest of forever with a hole inside you that couldn’t be filled?

When you died, you did not get to come back and see what you were missing. You didn’t get to apologize. You didn’t get a second chance.

Death wasn’t something you could control. In fact, it would always have the upper hand.

Everyone, Lacy thought, is somebody’s son.

People could argue that monsters weren’t born, they were made.

But true character showed when you could find something to love in a child everyone else hated.

So much of the language of love was like that: you devoured someone with your eyes, you drank in the sight of him, you swallowed him whole. Love was sustenance, broken down and beating through your bloodstream.

She didn’t know how the superintendent and the principal expected everyone to act—and they would all be doing that: acting—because to feel anything real would be devastating.

There were new rules: All the doors except for the main entrance would be locked after school began, even though a shooter who was a student might already be inside. No backpacks were allowed in classrooms anymore, although a gun could be sneaked in under a coat or in a purse or even in a zippered three-ring binder. Everyone—students and staff—would get ID cards to wear around their necks. It was supposed to make everyone accountable, but Josie couldn’t help but wonder if this way, next time, it would be easier to tell who’d been killed.

Had Peter’s anger been born of jealousy or loneliness? Or was his massacre a way to turn attention to himself, finally, instead of Joey? How could he formulate a defense that Peter’s act was one of desperation, not an attempt to one-up his brother’s notoriety?

Selena turned to him. “You know what the problem is here, don’t you?” “What?” “You think he’s guilty.”

“Right. But deep down, you don’t want Peter Houghton to get acquitted.” Jordan frowned. “That’s crap.” “It’s true crap. You’re scared of someone like him.” “He’s a kid—” “—who freaks you out, just a little bit. Because he wasn’t willing to sit down and let the world shit on him anymore, and that’s not supposed to happen.”

“You’ve never gone down the street and had someone cross it just because you’re black. You’ve never had someone look at you with disgust because you’re holding a baby and you forgot to put on your wedding ring. You want to do something about it—take action, scream at them, tell them they’re idiots—but you can’t. Being on the fringe is the most disempowering feeling, Jordan. You get so used to the world being a certain way, there seems to be no escape from it.”

Monsters didn’t grow out of nowhere; a housewife didn’t turn into a murderer unless someone turned her into one.

It was at the hands of his tormentors that Peter learned how to fight back.

Happiness wasn’t just what you reported; it was also how you chose to remember.

“God, I hope not,” Matt muttered from the desk behind Josie. He poked her shoulder and she pushed her paper to the upper left corner of her desk, because she knew he could see the homework answers better there.

Since Josie had started working at the copy shop, they’d been talking again, but—by unwritten rule—only outside of school.

Inside was different: a fishbowl where anything you said and did was being watched by everyone else.

Josie supposed that the flip side of this, the optimistic angle, was that Peter never tried to be like anyone else. She couldn’t lay claim to that herself.

You might find yourself, through no fault of your own, suddenly standing on the wrong side.

“Isn’t that obvious?” he said, and he took her hand, brought it to his lips, and kissed the knuckles so gently that Josie almost forgot all that had happened to get them to that moment.

If everyone else’s opinion is what matters, then do you ever really have one of your own?

although they always turned on Jerry Springer. Peter figured that was because no matter how much you’d screwed up in your life, you liked knowing that there were people out there even more stupid than you.

Ask a random kid today if she wants to be popular and she’ll tell you no, even if the truth is that if she was in a desert dying of thirst and had the choice between a glass of water and instant popularity, she’d probably choose the latter.

When you begin a journey of revenge, start by digging two graves: one for your enemy, and one for yourself.

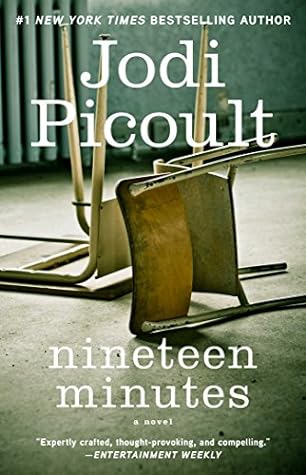

At the top of the display were two words: NINETEEN MINUTES.

“In nineteen minutes, you can mow the front lawn, color your hair, watch a third of a hockey game. You can bake scones or get a tooth filled by a dentist. You can fold laundry for a family of five. Or, as Peter Houghton knows . . . in nineteen minutes, you can bring the world to a screeching halt.”

Josie may not have initiated the teasing that Peter suffered over his middle and high school years, but she didn’t intervene either, and in Lacy’s book, that had made her equally responsible.

“I didn’t want to be treated like him,” Josie said, answering her mother, when what she really meant was, I wasn’t brave enough.

And difference is not always respected—particularly when you’re a teenager.

Adolescence is about fitting in, not standing out.”

“Everyone thinks you make mistakes when you’re young,” the judge said to Lacy. “But I don’t think we make any fewer when we’re grown up.”

once the world was pulled out from beneath your feet, did you ever get to stand on firm ground again?

He wished he’d taken more time to look at Peter when Peter was right in front of his eyes, because now he would be forced to compensate with imperfect memories or—even worse—to find his son in the faces of strangers.

Something still exists as long as there’s someone around to remember it.

Everyone would remember Peter for nineteen minutes of his life, but what about the other nine million?