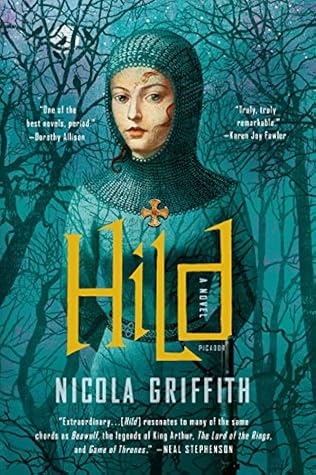

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“You’re forever finding things out.” “I’m the light of the world.”

It had been the principia of the Roman prefect, then the palace of the king of Ebrauc, and was now the feasting hall of Edwin, king of Deira and Bernicia. It was too big, too high, too hard. More stone than wood. Wealh. Really wealh, in a way Ceredig’s smoky great house had not been.

Auguries and sacrifice: crude tools of toothless petitioners. Or so her mother said, even as she’d rehearsed Hild in every variation. But she said, over and over, there was no power like a sharp and subtle mind weaving others’ hopes and fears and hungers into a dream they wanted to hear. Always know what they want to hear—not just what everyone knew they wanted to hear but what they didn’t even dare name to themselves. Show them the pattern. Give them permission to do what they wanted all along.

Edwin said, “You have seen this?” “Waking and sleeping.” Dreams were the most powerful of all prophecies.

In the evenings, with the light good for nothing but spinning and skeining, they joined the other women of the household in their gemæcce pairs, old woman with old, young with young, women who had woven and spun and carded together for years, through first blood and marriage and babies, who had minded each other’s crawling toddlers and bound each other’s scraped youngsters, and wept as each other’s sons and daughters died of the lung wet, or at hunt, or giving birth to their own children—all while they spun, and carded and wove, sheared and scutched and sowed.

Hild did what she always did when she couldn’t influence a thing; she stopped thinking about it.

Ellis and 1 other person liked this

But the life tree didn’t always fruit as expected.

That’s what the redcrests had done; they’d left. They left behind their stone houses in Caer Luel and beautiful white fountains, their red-tile roofs and straight roads, their perfectly round red bowls with pictures of dogs hunting deer around the rim, their exact corners and glass cups. And now the marble statues had lost their paint and stood melancholy white streaked with moss; tiles had blown off in storms and been patched with reed; men built fire stands directly on the cracked and broken remnants of once-brilliant mosaics. But the fountain still worked. It was a series of white stone

...more

Edwin raised his hand and shouted to the nearly three hundred gesiths remaining. “We ride in service to a dream from the gods. If our dreamer’s horse fails, you will give her yours. If her food runs low, you will give your own. She will light our way. And now we ride.”

“Though he would no doubt quote Jerome: Growing girls should avoid wine as poison lest, on account of the fervent heat of their time of life, they drink it and die.” He smiled to himself, as if remembering some sunlit girl and her fervent heat. “Yes. A man’s drink.”

“She should have been.” “But she is not. Remember that. The world is full of should-have would-have. As your poets say, ‘Fate goes ever as it must.’ You must, you must, learn to see the world as it is.”

Hild didn’t know whether to stab her sister or kiss her. But that’s what sisters were for.

“They’re useful to him?” “Very. They read.” They read. The sense of the world shifting was so strong she swayed in the saddle.

The message would cross the island in a day. It wouldn’t be garbled. It couldn’t be intercepted and understood by any but priests. Shave-pated spies. Not just skirt on one side and sword on the other but book balanced against blade.

“A snakestone,” Fursey said. “The local legend is of some harried god turning all the snakes into stone so that he could get some peace from the peasants’ pitiful petitioning.”

So who is to stop me? No one.” “Then I tell you truly, you must learn to stop yourself.”

Once again, Hild was struck with longing to have a home, year-round, where she could watch and learn a wood, a stream, a hillside in snow and fog and sun, in wind and rain, in summer and winter.

Fursey had told her that today would be the feast of Pentecost, which commemorated tiny tongues of flame dancing on saints’ heads. She wanted to see that. No wonder they did this by a river. She hoped Cian wouldn’t get burnt. She had warned him about the flames. He had wetted his head as a precaution. The brothers Berht had followed his lead.

He spoke too fast, and his accent was too strange for Hild to follow every word, but he seemed to be talking to someone called Satan. He sounded like a herald provoking an opposing army, taunting them with their imminent defeat, boasting of his champion’s skills and the worthlessness of his enemy. Paulinus’s cheeks grew mottled. He waved his crook. Hild wondered if it was a good idea to provoke an uncanny enemy when the sun was not quite risen.

She bowed. A king’s bargain. He gave her something worthless to him in return for something from her he wanted very much. But, there again, so did she.

Paulinus focused his black eyes on Hild. “My lord, this is not a conversation for women.” “She’s not a woman,” Edwin said with half-shuttered eyes. “She’s my seer.”

Edwin threw a duck bone at the man’s head. “You don’t like my seer? You’re in good company. My pet bishop doesn’t like her, either. He tells me he half expects her to dissolve and disappear in a shriek of oily smoke when she’s baptised at Easter.”

When she thought at all, she thought in British, the language of the high places, of wild and wary and watchful things. A language of resistance and elliptical thoughts.

The story of the Anglisc, woven with Woden back to the dawn of their songs. Ships. Fire. Bright swords. Kin and kine. Woods and wold. Hearth and home. Where was Christ in this? Christ didn’t fight. Christ didn’t farm.

Hild wondered how it must feel to have someone you didn’t quite trust make prophecies about what mattered most to you in the world.

He looked at her. His chest rose and fell in rhythm with hers, his brows arched like hers, his hair, the same colour as hers, clung to his nape just as hers did. They were the same height. But his eyes were a sharper blue, and the bones of his face heavier. They were the two great timbers of a doorway, massive, matched.

The king put his chin on his fist. “It seems we’ve been here before, Niece. If you’re so in love with your bog, by all means go slog about in it.”