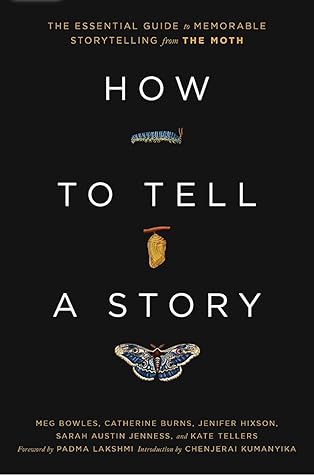

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Meg Bowles

Read between

August 19 - September 2, 2022

Inherent in this sentence are the plot and her arc.

“Well, what do you think the story is about in one sentence?” My heart always sinks, because I know it means what the storyteller is trying to convey is getting lost. I always dread that question, even though finding the answer will always (always!) make the story much better.

Defining what the story is really about early on helps you choose the details and moments to best support the story as you build it.

DIRECTOR’S NOTES Ask yourself: What are the stakes of your story? What did you feel you stood to lose or gain as a result? What did you most want/need/must have/couldn’t live without? Remember, stakes show us why you care, which tells us why we should care. Does your story go beyond anecdote? You might have dramatic details or a string of amusing events, but it must go deeper! Ask yourself why this moment left a lasting effect on you so you can transform your anecdote into a story. What is the arc of your story? Who were you at the beginning and who were you at the end? How were you changed?

...more

As you share the story, it’s as if you, the storyteller, are driving a car, and we, the audience, are in the passenger seat. You know exactly where you’re going, and which turns to take.

sometimes you slow down and stop to tell us about what we’re seeing

You do not need to literally include every step of the journey or every turn you took along the way. Jump cuts are allowed!

You just need to think about the important steps that will take us through your story. What info do we need to know to understand the bigger picture?

You can often jump-cut from one plot point to another without hurting the story. We don’t need to see you measuring flour and mixing the batter, just take the cake out of the oven.

Which parts of your story absolutely must have close-up detail, and which parts can you condense?

In a Moth story, the teller uses three elements to get us from beginning to end: SCENES illustrate parts of the story that are both compelling and critical to the arc. The climax of the story is almost always a scene. SUMMARIES move us through the time line and connect us to the next step (“three weeks later,” “after a lot of trial and error,” “I completed my master’s degree and was finally ready,” “two kids and a mortgage later…”). REFLECTIONS share your feelings and insights about what you learned, concluded, deduced, decided to change, or accepted.

here’s your daughter, and you do the very best you can with her. But no matter how hard you try, you’re going to mess her up.” He said, “We all do. But if you love her and you let her know how much you love her, she’ll forgive you.”

As the storyteller, you are in charge of how you use scenes, summaries, and reflections. You are driving this tour bus through your story, and you choose which scenes your “passengers” see—what we cruise past or where we pull over for a closer look.

The specificity of details brings the scene to life. Instead of it was raining, tell us about the noise of the rain on the roof or the puddles that blocked the path.

You draw these details out from any (or all) of your senses. How did something feel, both emotionally and physically? Was there a sweet smell or an eerie whistling sound? Did someone use a turn of phrase that sticks with you? Was there a thought that ran through your head in the moment?

We often forget the inner dialogue. It is equally if not more important to let us know what you are saying to yourself in the moment as it is to hear what you are saying out loud to everyone else.

When describing other people in your story, try looking for details and choices that will help us understand the character of that person the best.

THE PERILS OF DETAIL OVERLOAD Details can offer useful color, but don’t go overboard! Too many details can be distracting and fatigue a listener. If you go into great detail about something that doesn’t really connect to the rest of the story (e.g., if you digress and tell us about your uncle Al, when he isn’t particularly relevant), it can be confusing. Anytime a detail raises a question or causes a listener’s mind to wander, they’re off trying to figure out the answer to the question in their head while you’ve moved on. You lose your connection.

having too many vases on the mantel—you can’t fully appreciate the beauty of one when there are others competing for your attention.

Choose a few details that really shine and captur...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

We often have complex and conflicting opinions about events as they unfold. It is rare that we feel just one emotion. Multiple truths can exist in tandem, and you can acknowledge two or three (or more!) in a story.

Divulging too much information in social settings can be uncomfortable. Think twice before adding a TMI laundry list of pet peeves, the saga of your bum toe, or a trilogy of pet tragedies.

UNCOMPLICATE THE TRUTH. It is okay to simplify if the simplification feels honest.

EDIT TO MAKE THE TRUTH CLEARER.

OWN IT. Part of the honesty in a story is also taking stock of your part in it.

STAY IN YOUR OWN EXPERIENCE AND FEELINGS.

How do you know what they were thinking? To stay on track, tell us what you knew to be true:

I once had a storyteller tell me something awful that another person thought about him, and I said, They told you that?? and he said, No. So then I asked who told him and he said, No one, I just have a feeling that they think that. So I said, Okay then, just say that. Let it be YOUR feeling, don’t state an assumption as a fact!

harrowing,

Stories invite conversation. They encourage your “plus-one” to ask questions and share stories of their own.

smug

revel

Many of us have been taught that hiding our emotions is a survival skill. We’ve been told, “Hold it in, don’t show your cards. Don’t signal weakness.” However, in storytelling, bringing the full breadth of your feelings to the table is the power move!

If telling a story makes me feel vulnerable, it’s because I’m being real about who I am and what I experienced at a certain point in my life. When I am real, that’s when the audience will connect with me. If I hold anything back, there will be a distance between myself and the audience. If I’m developing a story, and it feels safe and easy to tell, I know I haven’t looked deep enough yet.

Shoehorning

levity.)

romp

vendetta

botched

This isn’t to say that you should default to making yourself the punchline of your story. Owning your flaws or onetime mistakes can be a way to create a connection—to paint a funny, honest picture of who you are and own the whole you.

“Do you understand what self-deprecation means when it comes from somebody who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility, it’s humiliation.”

Your story should create a connection with your audience, and that should never come at your own expense.

how she knows a personal anecdote or story is ready to go into one of her sermons. Nadia answered that she always tries to “preach from her scars and not her wounds.”

You have to control your story; the story can’t control you.

aughts,

scruffy,

gruff.

quirky

And then she just put her arm around my belly and started rubbing, and she said, “Can we go on the highway?” And I thought of all that we’d been through and all the suffering. And I said, “Yeah, we could do that.” So we got on I-95. And I had it up to eighty. And she was just screaming with happiness. Morphine bag was flapping over her head. And that wind—I always imagined the wind on a bike making you feel free, you know? It’s so powerful. And for ten minutes we were normal, and that wind just blew all the death off of us.

the three deaths, as celebrated in the Mexican tradition of Día de los Muertos: The first death is the failure of the body. The second is the burial of the body. The most definitive death is the third death. This occurs when no one is left to remember us.