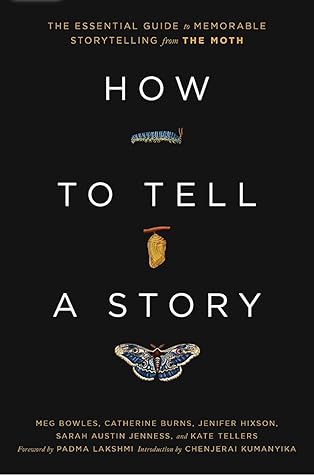

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Meg Bowles

Read between

June 15 - June 29, 2022

There are many forms of storytelling across time and cultures; this book will cover what we call “Moth-style” storytelling: sharing a true personal story, out loud and without any notes.

Moth stories are true and told out loud, in the first person. Moth stories are not read or recited. Moth stories always involve stakes and some sort of transformation. Moth stories are told within a specific time frame.

From the start, the content at the StorySLAMs was unpredictable and unruly. Not every story heard was one we’d want to hear, given a choice. A not-so-fun fact: Across this great land, there are thousands of people willing to take the stage to confess a story of a time they weren’t able to make it to the bathroom. Incontinence stories from Miami to Melbourne. (Technically, this does fall under the category of “vulnerable,” so hats off—pants off?—but we so dearly wish people would keep it above the belly button and bring the vulnerability of their hearts or minds and not their behinds.)

In your head, a story idea is just a theory. Test it by saying it out loud. Often when you say something out loud, it changes shape. When spoken, a story can feel less silly or scary.

Stories happen when expectations meet reality. Sometimes stories take place during an exception, an outlier event.

A beautiful toast gives the subject the gift of being seen.

Moth stories are all about agency—where something happens as a direct result of something you did or did not do.

MIKE BIRBIGLIA, MOTH HOST AND STORYTELLER: What I’ve found over the years is, you know you’re on the right track with finding a story if it makes you very uncomfortable to tell it. If you want to bail out at many stages of it, you know you’re going in the right direction.

Extraordinary accomplishments are a potential setting for your story, but not the story. Telling people about all the big wins in your life is a very easy way to lose your listener. You’re talking at them, you’re not inviting them in.

What it really comes down to is vulnerability. There is something comforting when people are willing to share the not-so-pretty sides of themselves. It’s as if they give the listener permission to relax. This is not a competition or an exercise to impress—I’m not perfect, so it’s okay if you’re not perfect too. When someone makes themselves vulnerable, the listener leans in, and a quiet bond is formed. It’s trust. This person trusts me enough to admit they screwed up or got it wrong. And that trust is the gateway to great empathy and memorable storytelling. It’s almost a cliché to say it now

...more

Remember not to let a trauma or a struggle be the story, but rather the context of the story. Stories always need to go beyond “a bad thing happened.”

A story that lacks stakes has no tension, and will fall flat.

People tend to use the words anecdote and story interchangeably, but actually they are quite different. An anecdote is a short, amusing account of a real incident or person. A story is beyond a string of occurrences; it deals with evolution. If you don’t want or need anything, it’s not a story. A good story builds. By the end, things have intrinsically changed. Something about it has a lasting effect. You can’t go back. You can’t unsee it. You can’t un-be it. You are a different person because of the events that unfolded.

A person who can turn job changes into narrative stepping stones that relate to one another will distinguish themselves.

As you craft your scenes, make sure to stay in the action and describe them from the inside. Be an active participant rather than a passive observer, and avoid telling from hindsight. Allow the moment to unfold the way it happened for you.

Resist the urge to tell a listener what to think or feel, and let them come to their own conclusion.

By following the arc to the conclusion, we do not mean you should say, “And then I realized…” Please avoid this phrase at all costs. Often, people will cue the change in the story by saying “And then I realized” or “In that moment.” As clean and neat as it would be for us as storytellers, very often the big moments of our lives don’t immediately change us. Sometimes they’re the catalyst for change, the first domino in a beautiful cascade. We may realize the magnitude of an experience only in hindsight.

Beyond eloquent and invisible construction of the story, emotion is the glue that connects storytellers and listeners.

When storytellers allow themselves to be vulnerable, to admit their flaws and anxieties and showcase their not-so-pretty sides, they allow the listeners to see themselves in the story.

A moment to laugh together is like a gift to the listener; it bonds you with the audience. It can be a way of taking care of them and giving them a brief moment of relief in the middle of an emotional scene.

Humor in storytelling should never feel forced, manipulative, or canned. Are you in the moment, or have you constructed the moment? The audience can feel the difference.

You can take an audience only as high as you take them low.

Some stories deal with shocking events and trauma. It’s important that the teller has done some healing before they try to share the details.

When directing upsetting stories, we pay attention to any signs that a story is still raw for the teller: Their drafts are late and dates to talk are rescheduled last-minute. In extreme cases, the storyteller may get lost in the details of a graphic scene. They are caught in the trauma while exploring the story, and when they stop talking, they might be disoriented. These signs can indicate that they may still be living the story and may not be ready to tell it publicly.

You have to control your story; the story can’t control you.

Take comfort in the idea of the three deaths, as celebrated in the Mexican tradition of Día de los Muertos: The first death is the failure of the body. The second is the burial of the body. The most definitive death is the third death. This occurs when no one is left to remember us.

If the structure feels awkward or complicated when you tell it, then it will probably end up sounding that way to your listener as well.

Note that the order of a story can take care of your listener. If a story explores a tragic event, and the listener can see it coming, it causes them to sit in painful anticipation. Sometimes that discomfort can serve a story, but often it can be distracting. If your audience is busy dreading, they aren’t hearing what you are saying. They are emotionally guarding themselves, and they aren’t fully connecting.

Flashbacks in live storytelling can be a bit tricky. You rely on the audience following you and being able to hold on to the different aspects of the story.

in the twenty-five years we’ve been directing stories, only a handful of storytellers have totally blanked on stage, and always—always!—they were the ones who relied heavily on word-for-word memorization.

The only things we suggest you memorize—and we stress, the only things—are the first and last lines of your story.

The one thing that will make an audience turn on storytellers is if they seem to be performing or disconnecting emotionally in some way.

DON’T PRACTICE TOO CLOSE TO SHOWTIME. We find that if you’ve rehearsed too recently, it’s easy to leave something out in the actual telling because you’ll think you’ve already said it (because you did…a few hours before!).

In her story “The Spy Who Loved Me,” Noreen Riols reminds us that “courage isn’t the absence of fear, it’s the willingness—the guts, if you like—to face the fear.”

The potential impact of a story is not limited to the moment it is told; it is long-term.

Encouraging loved ones to share their stories helps us to know them better, but also allows us to keep a piece of them with us after they are gone.

Telling our stories and listening to the stories of other people reminds us that we’re in this together. We are all making our way through a world that is sometimes joyful, oftentimes embarrassing, and never, ever perfect.

Most storytellers say that while it can be challenging to share a personal story, they felt it was truly important to do so. And it is important. To own your story is to take back the power—and challenge dominant and sometimes false (or even deadly) narratives.

Over the past twenty years, we’ve seen changes in the workplace that reflect social and cultural shifts. Sharing stories can be a way for employees on all levels to feel seen and heard at work and to move toward flatter hierarchies. Storytelling can be the social and emotional glue holding together morale and sense of purpose. It’s been proven to us time and again that storytelling belongs at work. We’re glad we took the call.