More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 26 - February 26, 2025

Like the bath, my old clothes could easily bring back poignant, painful memories. But I see in the clothes a symbol of continuing life. And proof that I still want to be myself. If I must drool, I may as well drool on cashmere.

There comes a time when the heaping-up of calamities brings on uncontrollable nervous laughter – when, after a final blow from fate, we decide to treat it all as a joke.

I at once placed myself under the protection of this brotherly symbol, guardian not just of sailors but of the sick – those castaways on the shores of loneliness.

Once I was a master at recycling leftovers. Now I cultivate the art of simmering memories.

‘Are you there, Jean-Do?’ she asks anxiously over the air. And I have to admit that at times I do not know any more.

I need to feel strongly, to love and to admire, just as desperately as I need to breathe.

The city, that monster with a hundred mouths and a thousand ears, which knows nothing but says everything, had written me off.

Had I been blind and deaf, or does it take the glare of disaster to show a person’s true nature?

Capturing the moment, these small slices of life, these small gusts of happiness, move me more deeply than all the rest.

Mithra-Grandchamp is the women we were unable to love, the chances we failed to seize, the moments of happiness we allowed to drift away. Today it seems to me that my whole life was nothing but a string of those small near-misses: a race whose result we know beforehand, but in which we fail to bet on the winner.

A voice reaches us, crying out from the depths of a profound silence: ‘I am alive, I can think, and no one has the right to deny me these two realities…’

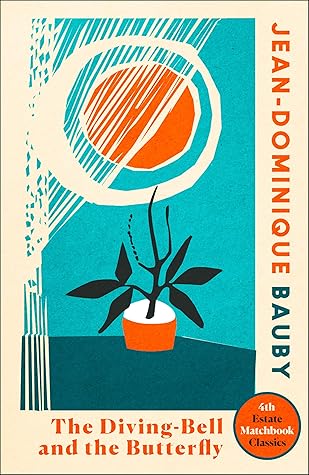

The man’s courageous spirit and the passionate tracking of a good story were combined in this supreme journalistic effort to produce a book whose vivid title describes the immobile state of his body (the deep-sea diver in one of those heavy old-fashioned diving suits) and the state of his mind, fluttering like a rare butterfly from letter to letter, from word to word, page to page, to the end of a book of just over 100 pages.

After the stroke that ended Jean-Dominique Bauby’s career as editor of Elle magazine on 8 December 1995, he confessed to weeping as his ambulance passed his former offices.

On 7 March 1997, Le Scaphandre et le papillon was published in France. Two days later Jean-Dominique Bauby died of heart failure, at the age of 44.

It is a vivid reminder that all of us, healthy and otherwise, have to live inside bodies that are terrifyingly vulnerable, and when those bodies go wrong, tough questions are raised about our place in the world’.