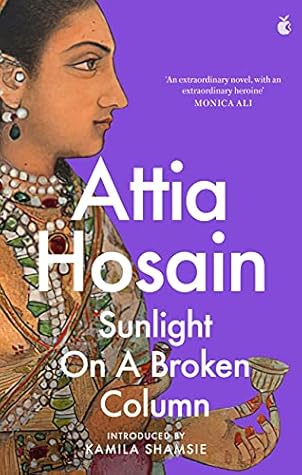

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

‘I resented and envied his cohesion of thought and action’,

Ramzano and Saliman giggled; they giggled more expressively than they talked, as if they were constantly finding and sharing a secret joke though life was reluctant in its kindness.

‘Make plans! But what if my plans don’t fit in with the plans others make? What if my freedom gets tangled with the freedom of others? Life is like knotted skeins of thread, and one gets caught in the tangle not knowing the beginning or the end.’

‘I wish someone could explain it to me,’ I argued. ‘Hamid Chacha talks to Saira Chachi no matter who is in the room. A thing can’t be shameful at one time and not another, for one person and not another. Besides if it is such a shameful business being married and having children, why talk of nothing but marriage from the moment a girl is born?’

We sat in the shade on the steps of the small, slender-pillared pavilion by the rose-garden and talked of days that had gone and wondered about the days that were to come.

I was frightened, recognising the voice of authority. Why must power always be used to humiliate?

At that moment, in the mirror, Zahra for the first time looked into the eyes of her husband. Zainab put her arm round my neck, trembling with excitement. I felt withdrawn and alien in my thoughts. That moment would have been the same had it been any other reflection Zahra saw. Did no shadow fall across the mirror? No reflection of pained eyes? Was love so pliable? Was it to be recognised only in poems of unrequited suffering? Why question what others accepted? Why was I allowed to become different?

The night was warm and heavy with the promise of rain.

We stopped for a moment, very still. ‘It looks as if nothing had changed.’ ‘As if our yesterdays had returned.’ ‘When we were impatient for our tomorrows.’

Everything in those days of my years ended with a question mark.

He said very quietly, as if talking to himself, ‘When I was a boy I used to sit at this window and look at the hills and the lake. Nothing has changed. I can still see a man’s profile in the shape of that peak over there; the same noises come up from the bazaar below; the same human ants move about. The toy yachts becalmed on the lake have not finished the race which started when I was a boy. The house has not changed, the garden hasn’t changed, the gardener hasn’t changed. These hill people grow no older. They treat me like a little boy. The coolies are the same, in the same rags, with the

...more

The conflicting values of the world that I lived in with my aunts Abida and Majida and the one I lived in now made me so full of doubts and questions, I retreated more and more within myself.

My sudden withdrawals and absences were irritants to those around me, and they accused me of indifference or absent-mindedness or selfishness, depending on their mood.

I feel just angry – and frightened too sometimes. Such hatreds are being stirred up. How can we live together as a nation if all the time only the differences between the different communities are being preached?

I had caught a glimpse of a withdrawn, settled sadness behind the love and joy that brightened her thin, pale face; but at the time I was too selfishly absorbed.

every nerve alive and quivering.

The silence in the house was more disturbing than the signs and smell of being uninhabited through the long summer and the season of the rains. It was not the peaceful silence of emptiness, but as if sounds lurked everywhere, waiting for the physical presence of those who had made them audible.

It appeared at times that neo-Indians wore their nationalism like a mask, and their Indianness like fancy dress.

it covered up the silence which I had learned to use as the only safeguard of vulnerability.

I made fun of you once, because I knew you were right and I did not have your courage.’

But in that moment of revelation by Aunt Abida’s dead body I learned that happiness had its own strength and was its own protection; sorrow needed to be shared.