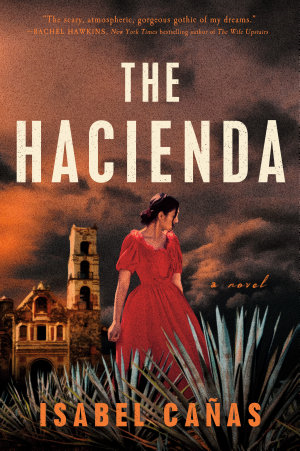

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Wandering the fields as a boy taught me agave flesh does not give like man’s; the tlachiqueros lift their machetes and bring them down again, and again, each dull thud seeking the heart’s sweet sap, each man becoming more intimately acquainted with the give of meat beneath metal, with the harvesting of hearts.

my eyes fixed on the horizon with the fervor of a sinner before their saint. As if the force of my grief alone could transcend the will of God and return that carriage.

It is said that mortal life is empty without the love of God. That the ache of loneliness’s wounds is assuaged by obedience to Him, for in serving God we encounter perfect love and are made whole. But if God is the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, if He is three in one in the Trinity, then God knows nothing of loneliness.

knew what the maguey felt. I knew the whine of the machete. I knew how my chest gave beneath the weight of its fall. I knew how it felt to have my heart harvested, sweet aguamiel carving winding wet tracks down my hollowed chest.

Industry will rise and fall, men will scorch the earth and slaughter one another for emperors or republics, but they will always want drink.

“You must be strong,” she said. “We must bear this with dignity.” With dignity. With silence was what she meant.

I chose to gamble on his secrets. Our relationship was founded on one thing and one thing only: my world was a dark, windowless room, and he was a door.

That was what I wanted. Someone who saw me not as darker than someone else, nor not quite as lovely as someone else. Not the daughter of someone. Not a piece to be played in a larger game. Someone who saw me for who I was and treasured me for it.

I folded up the darkest parts of myself and shoved my contorted spirit into a box that remained locked.

This tiny bit of the house was home now, and I would not rest until the remainder of it was as well.

I would scald its soot stains clean. I would strip its protective layer of dust and straighten its crooked edges, rebreaking and setting broken bones. I would make it mine, I would make it my home. My safe haven. I had no other choice, after all.

watched the priest as he held the Eucharist before us. The flesh beneath his chin trembled in the way of the well-fed as he spoke; the war had been easy on him. Not so of his congregation:

So long as the sinful parts of my pocked, split soul were crushed into submission, I was given a place to belong.

There was a wildness in her eyes that stopped my heart: that was the feral fear of hunted things.

Should is an oddly powerful word. Shame and anger have a way of flying to it like coins to lodestone.

In a way, I respected how she grated on Vicente’s nerves. She did not give a damn what anyone thought of her, as dangerous as that was for a woman of her station.

Passing through the gates of the property was like passing into a memory that no longer fit. I was a foot too big for a shoe, deformed by the world beyond as I returned to the landscape of my boyhood.

Years apart had not changed my role in the family: the sole surviving boy among a loud, bossy host of women, my job was to sit and listen, eat the food placed before me, and reach things stored in high places.

It was quiet. This was not the pious silence of holy places, nor the respectful hush of graveyards.

My God, why do You forsake Your people? Why do You not protect them from the gilded monsters that prowl the earth?

The women of my family sheathed their fears and sorrows in knives and claws; the sharpness of her voice did not offend me, but drove home how distressed she was.

“Some illnesses we cannot cure,” my grandmother said. “Others we can soothe. Sorrow is one of these. Loneliness is another.” She searched my face. “Do you understand? Tending to lost souls is our vocation.”

What wisdom was there sending a damned soul straight into the Church’s jaws, when I ought to be hiding from them?

“How can you know this is right?” I said, fear cracking my voice. “How?” “Ay, Cuervito.” She patted my hands. The touch of her gnarled hands was soft, but her dark eyes were steely in their confidence. “You will learn to feel it. When the time comes, you will know what is right.”

Useful. From Paloma’s tone, I knew it was meant to be taken as a compliment. But how I had loathed being called useful by Tía Fernanda. As if being of use to her was the only way I could earn any worth.

Mamá hated Rodolfo because of his politics. But perhaps that had cloaked something else, an instinct, an intuition. Rodolfo was not who I thought he was.

Perhaps I was frightened of him. But one could fear and trust at the same time:

But this time, I straightened. Curled my fingers tightly around my shawl. I was battered, exhausted, and frightened, but I was the daughter of a general, and I would not back down. I would not sit in the priest’s rooms alone, waiting for my fate to come to me.

Beyond the wall were more graves. No marble angels marked the earth, no grand statues of la Virgen. The divide between hacendados and the villagers extended beyond life.

The room was still. It was the emptiness of a tomb, airless, its belly filled with the absence of life rather than the presence of silence.

If I died in San Isidro, so be it. Perhaps Paloma’s bleak, oracular words had a power that bound me to this land. To this house. Perhaps one day I would stop fighting the voices and give myself over to madness at last. But it would not be today. I was the daughter of a general, and I was not done fighting yet.

“She knew he was a boy made of gunpowder. That letting him play with fire would be his end.”

He was Janus-faced, my husband. A creature of rage and violence on one side, a serene, gilded prince on the other. He was a staunch defender of the Republic and casta abolitionist who raped women who worked on his property. I could not trust him. Either side of him. I could not anger him either. Too many women had died in this house for me to test his patience.

Of course he did not question. Men do not trouble themselves with women’s bodies, save when they can be of use to serve or to sate them.

Since I met him, I had placed him on a pedestal as my savior, my protector against the darkness, my own private saint who kept the nightmares of San Isidro at bay. His injury rattled my faith in his omnipotence, but not my trust in his perfection.

Priest and witch, a source of curses and comfort.

While the leaping firelight made Padre Vicente look like a vision from Judgment Day, it softened the lines of Guillermo’s aging face.

There is no draft more bitter than that of helplessness.

My eyes stung with tears. What had I done wrong? Nothing. What could I have done right? Nothing.

“I wanted things too! I wanted to be safe. I wanted a home. And I got stuck with you.”

But mankind had already seen much evil and not been delivered. It would continue to see so much pain between now and the end.

I could taste in the air that the valley would have no respite tonight; the wind had other designs, and carried the clouds away from us, sloping southeast toward the distant sea.

This was the end. I had fought and I had failed. Would Papá be waiting for me, on the other side of agony?

Yes, I feared the hereafter. I was a sinner. I was a witch. I had sinned and would sin again, like all men. But whatever my decisions meant for life after death was between me and the Lord. All I could do was serve the home and people I loved using every gift I was born with.

He was a fractured creature, stretched between darkness and light. He belonged to this place in ways I could never comprehend, and he chose to keep belonging:

I guarded the memories of her last night in San Isidro fiercely, protecting them from the harsh light of reality. I was not ready to repent. I was not ready to let go.

I clung to any brunette on the page, desperate for mirrors that reflected my experience of feeling out of place in spaces that should feel like home.

a house haunted by both the supernatural and its colonial history.

I am leaving the academy to devote myself to the life of a novelist, a métier that demands that I close the history books and lie colorfully in the name of plot and character.

Colonialism has carved the landscapes of our homes with ghosts. It left gaping wounds that still weep.