More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

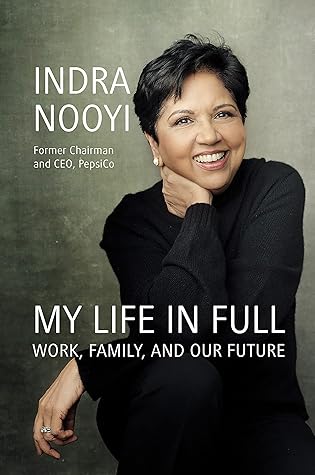

Indra Nooyi

Read between

September 20 - October 8, 2022

I am still the girl who grew up in a close family in Madras, in the South of India, and I am deeply connected to the lessons and culture of my youth. I am also the woman who arrived in the US at age twenty-three to study and work and, somehow, rose to lead an iconic company, a journey that I believe is possible only in America. I belong in both worlds.

My career had started when the dynamics between women and men at work were not the same as they are now. In fourteen years as a consultant and corporate strategist, I had never had a woman boss. I had no female mentors. I wasn’t upset when I was excluded from the customs of male power; I was just happy to be included at all.

The titans of industry, politics, and economics talked about advancing the world through finance, technology, and flying to Mars. Family—the actual messy, delightful, difficult, and treasured core of how most of us live—was fringe.

When I became PepsiCo’s CEO, in 2006, I laid out an extremely ambitious plan to address the underlying tensions in a company still rooted in selling soda and chips. I knew we had to balance supporting our prized Pepsi-Cola and Doritos brands with a full-throttle effort to make and market more healthy products.

I believe in the American story because it is my story. As a CEO, I once sat in the eighteenth-century, wood-paneled dining room at Chequers, the British prime minister’s country manor, and was asked why I had immigrated, thirty years earlier, to the US and not the UK. “Because, Mr. Prime Minister,” I responded, “I wouldn’t be sitting here lunching with you if I’d come to the UK.”

Moline, Illinois, on the Mississippi River, is 165 miles west of Chicago, surrounded by the corn and soybean farms of America’s heartland. In 1980, it was also home to Servus Rubber, a sixty-year-old maker of industrial work boots struggling with new competition from overseas. Servus was my first client as a management consultant.

I’d say. “There’s no way you can deliver the return you have assumed in your financial model.” This wasn’t popular—or effective. At some point, George Fisher, the CEO, noted my style and pulled me aside. “Be careful about throwing hand grenades,” he said. “You may turn people off even though you mean well.” George coached me to take a different tack, by saying, for example, “Help me understand how this comes together. As I see it, this technology platform requires a lot of investment and patience. Is it prudent to factor in a quick return?” Much as I hated this new, softer way of asking

...more

I wonder why I am wired this way where my inner compass always tells me to keep pushing on with my job responsibilities, whatever the circumstances. If I feel that I can help make something better, then I cannot stop myself from jumping in. I have a deep sense of duty and find it very hard to say no if someone asks for help. I love my family dearly, but this inner drive to help whenever I can certainly has taken a lot of time away from them—much to their dismay. I sometimes wish I were wired differently.

I loved my consulting career, although I’d always moved on from the client companies before my ideas were realized. Now I had the opportunity to see, smell, touch, and taste the business.

White American men held fifteen of the top fifteen jobs at PepsiCo when I walked in. Almost all wore blue or gray suits with white shirts and silk ties and had short hair or no hair. They drank Pepsi, mixed drinks, and liqueurs. Most of them golfed, fished, played tennis, hiked, and jogged.

corporate America in 1994. Even the most accomplished women were still milling around in middle management. The number of female CEOs among the five hundred biggest companies that year was zero.

I’d never had a close woman colleague with a job like mine and had never seen a woman in a workplace who was senior to me.

In bold moves, Roger cut back on building new restaurants and franchised existing locations from all our QSR brands to our best operators. This immediately improved our cash flow and return on capital. With franchisees running restaurants better, sales and earnings started to climb. Roger was viewed as a hero.

Good business demands tough decisions based on rigorous analysis and unwavering follow-through. Emotion can’t really play a part. The challenge we all face as leaders is to let the feelings churn inside you but then to present a calm exterior, and I learned to do that.

From 1994 to 1999, I worked and worked and worked. I’d go home at night, take a shower, put on my flannel nightgown to show the girls I wasn’t leaving, put them to bed, and sit up reading mail and reviewing documents until 1 or 2 a.m. I was almost never around for dinner. I didn’t exercise. I barely slept.

Of all the times I overdid it, one day still stabs at me. Mary Waterman, our lovely next-door neighbor, died of breast cancer. But I skipped Mary’s funeral because I stayed back at work rewriting slides related to the restaurant spin-off for the board, something that was really the responsibility of two others on our team. These men had just dropped the assignment on me, saying, “You do it so well and Roger trusts you.”

Tara was a calmer, quieter child, who once wrote me a note, which I still keep in my desk drawer, that lays bare the emotions of these years. On a big sheet of construction paper, decorated with flowers and butterflies, she begs me to come home. “I will love you again if you would please come home,” the note says. In her sweet, crooked printing, the word please is spelled out seven times.

I was sure I’d be miserable if I quit, and I wasn’t willing to step out totally. On a more practical note, we were still paying off some debt from the house renovation, and our expenses were high with two private school tuitions.

I think that leaders need to understand the details behind what they are approving before they affix their signature to anything. This is not about trusting the people that work for you. It’s about basic responsibility. Don’t be a “pass-through.” I think the people who worked for me came to appreciate that I read everything they sent me, both as a mark of respect to them and their work and because it was my responsibility. I know I drove people crazy with questions, but this was my job. I intended to do it well.

The press would gleefully build me up as a brilliant, different, new CEO so that when my inevitable troubles came along, I’d have farther to fall. That’s the game, he warned me.

But PepsiCo—and our whole industry—were also being bombarded with criticism that the sugar, fat, and salt in our products contributed to the scourges of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes in the US and, increasingly, the rest of the world. We had acquired Quaker Oats and had started boosting our nutritious offerings. We’d eliminated trans fats. We were adding omega-3s to Tropicana. We’d pulled full-sugar drinks from schools. Yet all this seemed marginal given the scope of our business. PepsiCo was still seen as a junk food company.

Our rivalry with Coca-Cola didn’t help matters. Coke had no food division, but Coke versus Pepsi was firmly embedded in the popular imagination. Our strategies and stocks were repeatedly compared, and any divergence surprised or worried the market. This made change tougher for us. We were always pinned to the cola wars. But, in reality, the two companies were very different. Unfortunately, the longtime beverage analysts and reporters who covered us were comfortably stuck on old comparisons as opposed to the new reality of our portfolios. It was frustrating indeed. For example, in 2006,

...more

Steve said he thought we should just cut half the sugar from everything. “But we’d have no company left,” I said, laughing. The respectable, formal, food-and-beverage industry and its long-term investors won’t tolerate the high drama that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs pull off, I said. Besides, people like sugar.

I noticed that when a male manager was evaluated, the talk would go like this: “He did a good job, delivered on most of his objectives, and . . .” and then some details about this man’s terrific potential. A woman’s evaluation would get a different twist: “She did a great job, delivered on all of her objectives, but . . .” and then some details about some kind of issue or personality problem that might derail her future success.