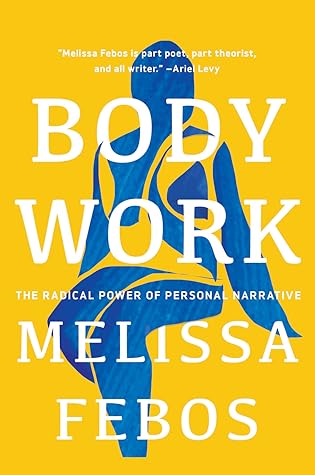

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 24 - December 5, 2024

There is no pain in my life that has not been given value by the alchemy of creative attention.

Writing is a form of freedom more accessible than many and there are forces at work that would like to withhold it from those whose stories most threaten the regimes that govern this society. Fuck them. Write your life. Let this book be a totem of permission, encouragement, proof, whatever you need it to be.

Since when did telling our own stories and deriving their insights become so reviled? It doesn’t matter if the story is your own, I tell them over and over, only that you tell it well. Should we not always tell stories so that their specificity reveals some larger truth?

But I suspect that when people denigrate them in the abstract, they are picturing women. I’m finished referring, in a derogatory way, to stories of body and sex and gender and violence and joy and childhood and family as navel-gazing.

Expressive writing about trauma strengthens the immune system, decreases obsessive thinking, and contributes to the overall health of the writers.

The articulation of painful memories, including the literature and art that arises out of political upheaval, is integral to the formation, preservation, and integration of collective memory.

Those who benefit from the inequities of our society resist the stories of people whose suffering is in large part owed to the structures of our society. They do not want to have to change. We see this in a thousand forms of white fragility, male fragility, and transphobic and homophobic tantrums protesting the ground gained by trans and queer storytellers. The resistance to memoirs about trauma is in many respects a reiteration of the classic role of perpetrator: to deny, discredit, and dismiss victims in order to avoid being implicated or losing power.

Social justice has always depended upon the testimonies of the oppressed. We cannot fully acknowledge the harms of patriarchy without a subsequent women’s liberation movement, just as we cannot fully acknowledge the harms and continued existence of white supremacist structures in our society without an anti-racist civil rights movement.

I’ll say it again, because it bears repeating: the resistance to memoirs about trauma is always in part—and often nothing but—a resistance to movements for social justice.

Don’t be mistaken: acknowledging all this is important, but it will not get your book published. Being healed by writing does not excuse you from the extravagantly hard work of making good art, which is to say art that succeeds by its own terms.

Writing about your personal experiences is not easier than other kinds of writing. In order to write that book, I had to invest the time and energy to conduct research and craft plot, scenes, description, dialogue, pacing—all the writer’s jobs. I also had to destroy my own self-image and face some unpalatable truths about my own accountability. It was the hardest thing I’d ever done. It made me a better person and it made my book a better book.

I want to feel on the page how the writer changed. How the act of writing changed them.

Navel-gazing is not for the faint of heart. The risk of honest self-appraisal requires bravery. To place our flawed selves in the context of this magnificent, broken world is the opposite of narcissism, which is building a self-image that pleases you.

“The work of the eyes is done. Go now and do the heart-work on the images imprisoned within you.”

No. We have been discouraged from writing about it because it makes people uncomfortable. Because a patriarchal society wants its victims to be silent. Because shame is an effective method of silencing.

I am still not free of it. To live by my own values rather than the ones prescribed me by a culture that remains invested in my silence is a choice I must make every day.

But white straight male writers are writing about the same things—they are just overlaying them with a plot about baseball, or calling it fiction. Men write about their daddy issues incessantly and I don’t see anyone accusing them of navel-gazing. I am happy to read those books; there are masterpieces among them. I just wish that male authors—along with the greater reading populace—were not discouraged from reading such books by women.

These stories are thought of as niche, identity related, while white and male stories are more likely to be seen as universal, which is an old chestnut of white supremacist patriarchy.

Sometimes, while writing this book, a question intruded: who cares? I snapped out of the reverie of my work, struck by a sudden fear that I was wasting my time, indulging subjects that had already been written about. While the question of who cares is an important one for every writer to ask themselves, embedded in my contemplation of it were more than thirty years of conditioning to believe that the subject of girlhood was not worth a few hours of a reader’s time.

I don’t believe in writer’s block. I only believe in fear. And you can be afraid and still write something. No one has to read it, though when you’re done, you might want them to. One of the epigraphs of my second book—though it could be an epigraph for my life—is a quote from the British psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott: “It is joy to be hidden and disaster not to be found.”

To William H. Gass’s argument, “To have written an autobiography is already to have made yourself a monster,” I say that refusing to write your story can make you into a monster. Or perhaps more accurately, we are already monsters. And to deny the monstrous is to deny its beauty, its meaning, its necessary devastation.

We are writing the history that we could not find in any other book. We are telling the stories that no one else can tell, and we are giving this proof of our survival to each other.

Don’t tell me that the experiences of a vast majority of our planet’s human population are marginal, are not relevant, are not political. Don’t tell me that you think there’s not enough room for another story about sexual abuse, motherhood, or racism. The only way to make room is to drag all our stories into that room. That’s how it gets bigger. You write it, and I will read it.

Over time, we start to narrow our thinking about what a piece of writing—what a certain story—can be, how it needs to be told. Partly, this is because we get attached to the most familiar narrative. We get attached to the one we tell ourselves, because it makes persisting easier. It makes us feel better about ourselves. It excuses us. It excuses others.