More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I am a banshee, but cannot get comfortable with being one, am always swinging from bansheeism to playacting sweetness and back. The truth is I cannot play nice and don’t want to, but want to want to, some days.

In Trout Canyon I told my mother that all I wanted was for us to be normal, a normal family. She said, Oh honey, there’s no such thing.

Bad vibes indeed and these confirmed for me that we’d always be two families, two houses. The Tecopa house and the Navajo house. One family of four, one family of five. We—my mother, Lise and I—missed the Tecopa house as we missed my dad. Grief was a river running under the three of us, all but invisible to Ron and Lyn. We couldn’t help it.

I was on the yearbook committee and put so many pictures of myself in it that the class of 2002 called it the Claire Bitch Project.

Another way is, She had her mother’s pain swimming in her blood and her mother’s and her mother’s and her mother’s and she was fat with

She said we three girls had the same hands, artist hands. She taught us jewelry making, photography, breaking and entering. To scavenge and build and refurbish, to scam and steal and to bullshit.

She and I loved but no longer understood each other. Motherhood had wrenched us into separate spheres—she the attachment parent, me the detached mother.

“I’d love to, believe me,” I said. “But I promised my therapist I’d stop doing things that make me feel like a fraud.” “You’re not a fraud,” said Ivy supportively. “Just a slacker.” “A slacker,” Ty put his hand on my shoulder as if he’d read it somewhere in a manual, “and a bit of a coward.”

My team of mental health professionals in particular didn’t seem to understand that I wasn’t comforted by being normal, that I took normal as an insult, that knowing these troubles were widely felt didn’t ease them, only meant that on top of my avoidance and guilt and shame and numbness I now felt boring, a kind of death. Knowing all this was normal put me somewhere on the scale of pathetic to suicidal. I thought, If this is normal, count me out.

Motherhood had cracked me in half. My self as a mother and my self as not were two different people, distinct.

My problem is I can’t figure out how sorry to be for the way I’ve been. I’m either a little sorry, very sorry, or not at all sorry.

About marriage and motherhood. Is it as bad as you say? Can you really not be an artist? Are all the holidays ruined?” I thought about it. “Some get better, actually. Christmas. Halloween. All you need on the Fourth of July is a box of sparklers. Pregnancy makes you appreciate your body kind of. And living with another person is . . . nice. Things appear, get bought even though you didn’t buy them, get cleaned even though you didn’t clean them. They get fucked up too, by the kid, but even that’s kind of magic. You turn around and something’s in shards—something you were given, something you

...more

“I’m unhappy,” I said. “I know happiness is a scam, but . . . unhappiness is real.”

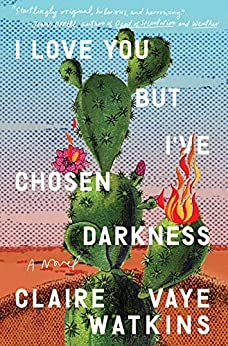

His collarbones said I love you but I’ve chosen darkness. With a period, as in end of discussion.

it made sweet boys afraid of me so that I always ended up with the crazies but in this manner I went from being raised by a pack of coyotes to a fellowship at Princeton where I sat next to John McPhee at a dinner and we talked about rocks and he wasn’t at all afraid of me.

“What were your vows?” “We wrote our own.” “What kind?” “Ambivalent atheist vows.” “What did they say?” “Mine said basically, ‘I’ll try.’ ” “Did you?”

Jesse, I do not want to hurt the baby or myself. I am not choosing darkness but darkness is choosing me.

“How’s she doing, your sister?” “Honestly she’s kind of a mess,” I said. “Walked out on her husband and baby.” Dottie, her name tag read. “Yep, well.” Dottie shrugged. “It’s a messy business being alive.” —

“I liked him before he died.” “But you liked him more after. They’re easier to love, the dead ones.” At that she had to scoot.