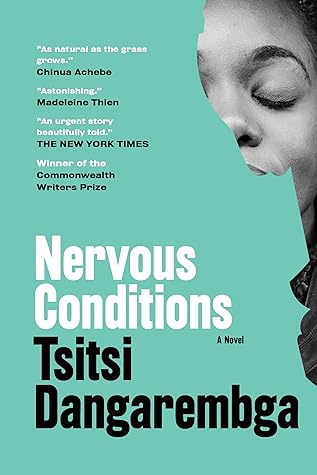

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 24 - September 29, 2025

At times like that I wanted so badly to disappear that for practical purposes I ceased to exist.

Three young men came up to me and told me they fancied me, but I could see from the way they talked that they really fancied themselves.

Babamukuru condemning Nyasha to whoredom, making her a victim of her femaleness,

The victimisation, I saw, was universal. It didn’t depend on poverty, on lack of education or on tradition. It didn’t depend on any of the things I had thought it depended on. Men took it everywhere with them. Even heroes like Babamukuru did it. And that was the problem.

But what I didn’t like was the way all the conflicts came back to this question of femaleness. Femaleness as opposed and inferior to maleness.

I didn’t want to explore the treacherous mazes that such thoughts led into. I didn’t want to reach the end of those mazes, because there, I knew, I would find myself and I was afraid I would not recognise myself after having taken so many confusing directions.

If there had been sons earlier, they would have helped the old man on the land. The family would have been better off than they are now. Besides,’ they added significantly, ‘a man can’t be sure about daughters!’

I am not sure who propositioned whom, but in a very short time after Takesure’s coming Lucia was carrying his baby. Naturally, people said she had done it on purpose in order to snare a husband.

Naturally I was angry with him for having devised this plot which made such a joke of my parents, my home and myself. And just as naturally I could not be angry with him since surely it was sinful to be angry with Babamukuru. Babamukuru who was my benefactor, my father for all practical purposes and who was also good, deserving of all love, respect and obedience. So I banished the anger.

Nyasha gave me the impression of moving, always moving and striving towards some state that she had seen and accepted a long time ago.

I did not want to be left behind.

Lucia was careful not to be provoked. ‘You know why I’m waiting? For my sister, isn’t it? As soon as my sister makes up her mind what she wants, you won’t see me here any more.’ My father and Takesure found this amusing. They had a good laugh at Lucia’s expense. ‘Now what is this I am hearing!’ gurgled Takesure. ‘The woman thinks she can go away. Just like that. Now, Lucia, where do you say you will go? Aren’t you waiting for me to take you to my home?’

‘why do you keep bothering me with this question? Does it matter what I want? Since when has it mattered what I want? So why should it start mattering now? Do you think I wanted to be impregnated by that old dog? Do you think I wanted to travel all this way across this country of our forefathers only to live in dirt and poverty? Do you really think I wanted the child for whom I made the journey to die only five years after it left the womb? Or my son to be taken from me? So what difference does it make whether I have a wedding or whether I go? It is all the same. What I have endured for

...more

‘Ha! Ya, Mukoma,’ agreed my father. ‘There was a job there! You should have seen us! Up there with strips of bark and the fertiliser bags, and tying the plastic over the holes. Ha! There was a big job there, a big job.’ Lucia and I could not hide our smiles. ‘See, Jeremiah,’ praised Babamukuru, pleased with my father’s labour, ‘even your daughter is pleased when you have done a good job.’

Above all, I did not question things. It did not matter to me why things should be done this way rather than that way. I simply accepted that this was so. I did not think that my reading was more important than washing the dishes,

There was definitely something wrong with me, otherwise I would have had something to say for myself. I knew I had not taken a stand on many issues since coming to the mission, but all along I had been thinking that it was because there had been no reason to, that when the time came I would be able to do it.

My mother had been right: I was unnatural; I would not listen to my own parents, but I would listen to Babamukuru even when he told me to laugh at my parents. There was something unnatural about me.

Tambudzai is being punished because she did me wrong. It is not that, Lucia, but children must be obedient. If they are not, then they must be taught. So that they develop good habits. You know this is very important, especially in the case of girls. My wife here would not have disobeyed me in the way that Tambudzai did.’

‘Ma’Chido,’ Babamukuru was saying pacifically, ‘these are not good words.’ ‘No, they are not,’ Maiguru retorted recklessly, ‘but if they are not good things to be said, then neither are they good things to happen. But they are happening here in my home.’ ‘No, Ma’Chido,’ soothed my uncle. ‘It is not as you say.’ ‘It is as I say,’ she insisted.

She did not know what essential parts of you stayed behind no matter how violently you tried to dislodge them in order to take them with you.

She thought there was a difference between people deserting their daughters and people saving themselves.

was delighted that people, white people for that matter, thought my background was interesting. I thought I should tell them about Babamukuru as well, to show them that my family had a progressive branch, but they were more interested in my own father and my life on the homestead.

Marriage. I had nothing against it in principle. In an abstract way I thought it was a very good idea. But it was irritating the way it always cropped up in one form or another, stretching its tentacles back to bind me before I had even begun to think about it seriously, threatening to disrupt my life before I could even call it my own.

‘It wasn’t a question of associating with this race or that race at that time. People were prejudiced against educated women. Prejudiced. That’s why they said we weren’t decent.

medium could not help whereas I could, by not going to Sacred Heart. But this was asking too much of me,

If I forgot them, my cousin, my mother, my friends, I might as well forget myself.

‘Have a good time, you African,’

They think that I am a snob, that I think I am superior to them because I do not feel that I am inferior to men (if you can call the boys in my class men). And all because I beat the boys at maths!

We’re grovelling. Lucia for a job, Jeremiah for money. Daddy grovels to them. We grovel to him.’ She began to rock, her body quivering tensely. ‘I won’t grovel. Oh no, I won’t. I’m not a good girl. I’m evil. I’m not a good girl.’ I touched her to comfort her and that was the trigger. ‘I won’t grovel, I won’t die,’ she raged and crouched like a cat ready to spring.

Look what they’ve done to us,’ she said softly. ‘I’m not one of them but I’m not one of you.’

the general theme of remembering and forgetting that runs through your story; the danger of forgetting and the protagonist's certainty that she won't

forget. Her very writing is a remembering - a very thinking constructive kind of remembering, not just telling the story or stories, but about them and interpreting them.

‘The problem is the Englishness, so you just be careful!’