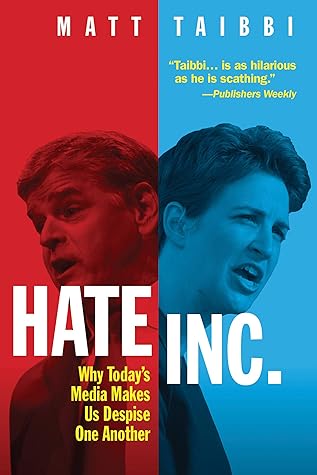

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Matt Taibbi

Read between

March 19 - April 3, 2021

Halperin sold himself to other reporters as the oracle of the political elite. He claimed to have his finger on the pulse of what he called the “Gang of 500,” a group of “campaign consultants, strategists, pollsters, pundits, and journalists who make up the modern-day political establishment” and have the “inside dope” on where the country is headed.

There were real angles on Thompson, who had been a U.S. senator and, worse, a longtime lobbyist who had represented everyone from nuclear power companies to Haitian dictator Jean-Bertrand Aristide to the Tennessee Savings and Loan Association. His wife worked for Burson-Marsteller, the PR/lobby firm that had represented practically every corporate malefactor on earth, from Union Carbide to the makers of the Dalkon Shield. But all I heard on the bus was a debate between reporters about whether or not Thompson was the next Reagan or a hapless lazybones, as if the two things were incompatible.

The most honest take on this issue is that in the media, we mostly have no clue if a politician is working hard or not.

McCain’s idea of campaigning early in the 2008 race was a couple of midday stops to tell jokes at VFW halls. But unless someone like Halperin identified this as a problem, nobody would notice.

A little later, in an Iowa debate, Republican candidates were asked to raise their hands if they believed climate change was real and caused by humans. Thompson snapped, “I’m not doin’ hand shows.” The other candidates cheered. He was wrong and insane, but at least he was “standing out” and not being “passive”

“Memo to Fred,” Crowley wrote. “It’s a stupid and debasing process. But you can’t fight it.” Exactly: you have to embrace it. This is how we got Donald Trump.

This is Punditry 101. You make up some meme like “lazy Fred” or “the Wimp Factor” (Bush I) or the “Bore Effect” (Gore), and insist the candidate needs to beat the rap to win. If the politician is obedient enough in trying to do so, you start talking about how he or she is “turning things around” or “reinvigorated,” and the candidate will magically begin getting good press.

I do this for a living and I can’t make sense of these takes. Obama was supposedly too passive in the first debate. Now he interrupts mock-Romney in a practice debate and his top aide David Axelrod is “aghast” because… why exactly?

First-term Obama gave a massive blank check to corrupt Wall Street, expanded a revolting covert drone assassination program, and greatly widened the president’s powers of secrecy and classification, while prosecuting leakers (and even journalists) in record numbers.

For decades, we told audiences that being “professorial” or “boring” or “answering questions” was a negative. We so predictably ripped politicians for these qualities that the smart ones like Obama learned to apologize for being “polite.”

Assholes like Heilemann and Halperin are part of the reason voters picked Trump in the first place.

People got so tired of watching politicians do stupid pet tricks for gatekeeping snobs that they voted in huge numbers for the first politician with the nerve to flip the script, which absolutely happened in this case. Trump had these idiots riding around on a Zamboni, for God’s sake.

Trump grievously offended nearly every voting demographic. He teed off on women, Latinos, Muslims, the disabled, “the blacks,” veterans, and Asians (“We want deal!” he cracked, about the Chinese).

But he won anyway. This should have proved “electability” was a crock, and killed it forever as a form of campaign analysis.

Electability is the same kind of alchemy, about as scientific as chicken-bone divination, that nonetheless routinely impacts devastating real-world decisions.

The amazing closeness of American elections has never made sense. In a country in which 10 percent of the population owns 90 percent of the wealth, you’d expect the very rich to be a permanent electoral minority. That it doesn’t work out that way is odd. But this is not the kind of observation pundits tend to make. Instead, we peck around the surface.

The trick was using polls to convince voters to interpret political news through someone else’s eyes, instead of their own brains. You may like the policies of candidate X better, but “polls say” (this use of the passive voice is key) you should vote candidate Y, if you want to win the election.

Both parties and their main donors consistently threw, and throw, their money behind candidates who check all of these boxes. This person becomes the presumptive frontrunner. Campaign reporters would then trail along—I’ve watched this many times—and prod would-be voters at events to comment on the candidate’s superior “electability.”

If you were a reporter following Kerry, you felt like you’d died and woken up in a vat of boiling grease. The man was pure distilled boredom. He had no clue why he was running for president.

Matt Bai of the New York Times later summed up 2004 as follows: “In this year’s campaign, electability became the issue itself.”

never had been before. In 2000, New Hampshire voters answering exit surveys had listed “best chance to win in November” as their primary reason for choosing a candidate just 7 percent of the time. By 2004 they were listing it as the primary reason between three and five times as often. In Iowa, an amazing 50 percent of voters listed it as their chief concern. We were asking the fuck out of that question.

The whole “electability” question usually implies a) there’s a candidate in this field who’s most likely to win, and b) there’s a candidate who appeals to you on a policy level, and c) those candidates are not the same person.

Most people are terrified of throwing their vote away, so they’ll steer clear of any candidate the press tells them has no chance.

The “polls say” trick also works, sadly, with labor. Every year, even in the primaries, unions endorse candidates with poor records on labor, because they buy the “electability” pitch.

“We need a seat at the table,” is what one of the union men told me, implying that it was better to back a weak-on-labor Democrat with a shot than a good one with none.

I told Kucinich about this exchange. He sighed and said that until people learned to vote according to their own beliefs and preferences, politics would be a “mirrored echo chamber, where there’s no coherence.”

Very few campaign journalists ever raised an eyebrow about this, though, until polls stopped being able to predict it. This is a kinder way of saying that in 2016, voters started to blow off polls, which threw the whole business into disarray.

“Electability” was essentially conventional wisdom in search of scientific recognition. When fivethirtyeight.com appeared on the scene, campaign reporters—I heard this—felt their made-up takes were finally being sanctified by data. I remember, in particular, a debate about Sarah Palin in the later stages of the 2008 race.

Reporters breathed a sigh of relief. The “beer test” was still a thing, just not in this particular situation! Nobody had to come out and say, “All that stuff we’ve been saying about beer was irrelevant and irresponsible.

The problem was that Silver’s predictions were based on a generation of voter behavior skewed by mountains of our goofball campaign reporting and idiotic conventional wisdom. Should voters ever tune us out, all that data would become meaningless overnight.

The thing was, nobody in the press had any clue what would happen if people stopped listening to our “electability” horseshit. There was no data on this. We were about to find out.

There was a big lesson in this for everyone, or there should have been. Politics, despite the fact that it talks about itself as baseball all the time (“inside baseball” is the favored term of people who think they’re playing it), is not baseball. In baseball, batters don’t intentionally strike out because they’re told the pitcher has high strikeout rates.

The easiest way to predict what kinds of “electability” stories you’ll see in an election season is to look at the field of candidates and see which ones have a lot of lobbying and ad money behind them. Those candidates will be described as electable. Everyone else will get the “polls say” treatment. Be wary of our version of junk science.

When we talk about “party elites” deciding elections, what we really mean is that institutions like the press, the two political parties, and corporate donors can throw up insuperable obstacles to anyone they please.

Then the few hundred people who actually matter in Washington will get their heads together and quietly decide which candidate is going to get the money for the next run. That candidate ends up with a few hundred million bucks and a head start with the press.

In the convention in Chicago that summer, Democratic party bosses nominated Humphrey on the first ballot despite the fact that the other two candidates had won the votes.

Note: if you’re discussing campaign dynamics in America, you can’t avoid terms like “purist” or “purity.” These are descriptors invented for people who insist on voting for the candidate of their choice, like for instance an antiwar voter who won’t vote for a pro-war candidate. Snobs!

In 2016, Jeb Bush won the Republican “invisible primary.” This was all but officially announced before the race began. Romney’s 2012 finance chair, Spencer Zwick, said in February of 2015 that anyone who “wants to be taken seriously running for president” (read: seeks assloads of money from my donor list) needed “to be in a similar place” to Jeb Bush policywise.

“For all these other candidates, the first question is: Where are you going to get the money?” said David Brock, a prodigious fundraiser who speaks with donors often and runs a constellation of Democratic groups and super PACs. “If you can’t answer the question of where you’re going to get the money, you’re not going to go anywhere.”

The “invisible primary” was core belief for campaign reporters through 2016, when the Trump campaign exploded the thesis. It wasn’t just that Trump won the nomination in defiance of party chiefs, it was that the party-approved candidate, Bush, was not remotely competitive. This (along with the surprisingly vibrant challenge of Bernie Sanders on the other side) spoke to a massive collapse in the influence of political elites with voters. But that issue has not been addressed head-on by the press.

The more we turn up the heat on the red-versus-blue hatred down the stretch, the less voters think about chummy early processes like the “invisible primary.” And boy, do we have a lot of ways to make things heated.

Richards saw the parallels right away. But almost no one in blue America spotted this, least of all the press corps. This was malpractice on one level—to be that out of touch with so popular a phenomenon was inexcusable—but it proved dangerous also, as reporters didn’t recognize that they were sliding into a known business model.

In the late fall of 2015, when Trump started to rise again in the polls, I started to see reporters on the trail carrying around Mein Kampf or The Paranoid Style in American Politics. They were looking for political parallels in the past.

Throw an attention magnet like Trump into a political journalism business that feeds financially off conflict, and what you get is the ultimate WWE event.

Meanwhile, the Washington Post by that first night was running chin-scratching analyses like, “Donald Trump’s ‘Schlonged’: A linguistic investigation.” With its unique brand of unimaginative pretentiousness, the paper somehow managed to cite quotes from both Ben Franklin and Harvard University professor Steven Pinker. The Pinker quote read: “Headline writers often ransack the language for onomatopoeic synonyms for ‘defeat’ such as drub, whomp, thump, wallop, whack, trounce, clobber, smash, trample, and Obama’s own favorite, shellac (which in fact sounds a bit like schlong).”

Just prior to Trump’s “schlong” comments, Barack Obama had signed the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act, a landmark law giving the government access to more of your private data. The Fukushima disaster was still causing hundreds of tons of radioactive water to spill into the ocean. A new study had even been released suggesting search engines had poorly-understood abilities to influence elections—these same papers would care a lot about this later, but not now. Everybody was having too much fun with “schlong.”

By the next morning, on December 23 Hillary ally and chief media attack dog David Brock was barking Trump’s own words back into the ether. Brock said “Hillary schlonged by Obama” was “racist” and made Obama out to be a “black rapist.”

Trump got David Brock to call Barack Obama a “black rapist” and had a female reporter from Forbes magazine interviewing a rabbi about admiring schlongs in locker rooms.

But there was synergy between a game show host building up his Q rating and a commercial news media whose business model thrives on conflict and was often starved for the real thing. Reporters who’d spent years concocting dubious features about the “Gore Bore” problem or the “Wimp Factor” now had a real presidential front runner talking about “schlonging” a female rival. Ka-ching!

NPR was entering “schlonged” in the list of possible “words of the year.” Trump meanwhile was managing to turn all of this into a referendum on Bill Clinton, who made the mistake of jumping in and describing “schlonged” as part of Trump’s “penchant for sexism.” Trump turned around and blasted Clinton’s own history with women, and got even “enemy” publications to bite. A huge triumph was the December 28, 2015 piece in the Washington Post: “Trump is Right: Bill Clinton’s Sordid Sexual History is Fair Game.”