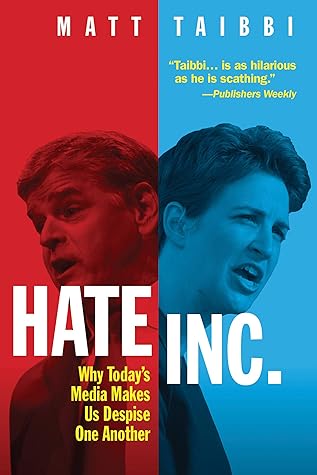

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Matt Taibbi

Read between

March 19 - April 3, 2021

More recently, we’ve cycled through a series of unconvincing responses to Why do they hate us?—themed stories like Brexit, the Bernie Sanders primary run of 2016, and the election of Donald Trump.

Everyone hates the media. Nobody in the media seems to understand why.

Some of this surely has to do with the fact that the media business, at least at the higher end, has been experiencing record profits since Donald Trump tabbed us the “enemy of the people.” In the “Democracy Dies in Darkness” era, many in the press wear their public repudiation like badges of honor, evidence that they’re on the right journalistic track.

Later, as Trump cruised toward the nomination, media execs couldn’t hide their excitement. Since-disgraced CBS jackass Les Moonves blurted out that Trump “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” adding, “the money’s rolling in.”

Cruz was routed in Indiana after Trump took the highly creative step of accusing Cruz’s father of helping assassinate John F. Kennedy.

But Cruz didn’t get it and actually denied the JFK charges, which of course had the practical effect of just making us think about them more.

The pretense that the presidential campaign was anything but an insane, absurdist reality show was almost completely gone by that point.

the campaign process, for a generation, has been too long by at least a year.

Kerry himself then lost to George W. Bush when the press flunked him by another asinine standard, the now-infamous “likability” test.

Heading into the 2016 race, pundits openly celebrated all of this. We were proud of the dumbed-down barriers to political power we’d created.

We even made Barack Obama submit to this horseshit. “The president has been polishing his ‘regular guy’ credentials by talking a lot about beer,” explained NPR (NPR!) in 2012.

Trump was a demon from hell sent to punish all of these reporting sins.

Yet very few picked up on the fact that the joke was on us, that Trump was winning votes precisely by running against our sham beauty contest.

High priests of conventional wisdom like Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times began running pieces in early 2016 with titles like, “My Shared Shame: The Media Helped Make Trump.”

It was obvious that Obama had deeply held feelings about the subject. This made sense given Trump’s role in pushing the vicious birther campaign. Trump was one of the few figures capable of inspiring Obama to break character.

It was eye-opening to see how quickly my colleagues ran from their own “likability” cliché once it began to look like it might be a factor in the increasingly infamous race.

Characteristically, there was no remorse over the fact that we had overemphasized the likability factor for a generation, helping ruin the candidacies of wonky dullards like Mike Dukakis, Al Gore, John Kerry, and even Mitt Romney in the process.

“How much do voters have to like their politicians?” wondered Time, the same magazine that had put a giant black-and-white photo of Hillary over the headline LOVE HER HATE HER (check one) in 2006, back when this sort of analysis was not considered world-imperiling stupidity.

The Atlantic in 2012 had reinforced the cult of likability with a long piece explaining Obama’s dominance over Romney by writing, “In every instance [since 1984] the candidate seen as more likable won the election.” In 2016, the same outlet trashed likability as a moral wrong, saying we shouldn’t want a leader on our level, but one “demonstrably above us.”

Conveniently for our sales reps, the new dictum centered around the idea that we not only should not reduce the volume of TrumpMania, but rather we must, if anything, increase it, because we now had an enhanced “responsibility” to “call him out.”

Later in the summer, in a seminal op-ed in the New York Times, writer Jim Rutenberg argued that we reporters had an obligation as citizens to ward off the historical threat Trump posed. Because Trump was a demagogue who played “to the nation’s worst racist and nationalistic tendencies,” you had to “throw out the textbook American journalism has been using for the better part of the past half-century” and “approach [Trump] in a way you’ve never approached anything in your career.” Rutenberg argued that journalists had to cast ourselves free of the moorings of “objectivity,” and redefine

...more

Bad candidates and bad politicians looked bad even under the old “objectivity” standard, the old language, the old headlines. What were we changing and why?

An increased effort to scrutinize this candidate, call out his shit, etc., would hurt him at the polls, the theory went.

What Rutenberg really meant by giving up “balance” wasn’t going after Trump more—we were already calling him every name in the book—but de-emphasizing scrutiny of the other side.

the paper was reveling in a so-called “Trump bump” in subscriptions, with the fourth quarter of 2016, when the Times had the honor of giving horrified audiences the bad news about Trump’s election, being its best year since it launched a digital pay model.

By the summer of 2018, however, the “Trump bump” was gone and the paper was seeing most of its digital growth in crosswords and cooking. However, it still had the honor of having ditched its long-standing and hard-won reputation for objectivity in pursuit of a few quarters of growth.

The Times ran a piece in October pronouncing the race essentially over, telling us to expect a “sweeping victory at every level” for Clinton. The papers all throughout the race were full of confident predictions and demographic analyses with titles like, “Relax, Trump Can’t Win” and “Donald Trump’s Six Stages of Doom.”

On the other hand, such reports got lots of clicks from blue-state voters, thanks to the same dynamic that inspires sports fans to read rosy predictions even when their teams suck. The vibe was closer to fanboy homerism (which incidentally is completely defensible in an entertainment genre like sportswriting) than to “advocacy reporting.”

Trump’s victory came as a complete shock to millions in large part because of this quirk in the sub-genre of data reporting, whose whole purpose was to be a buffer against conventional wisdom and groupthink.

Election Day, 2016 was a historic blow to American journalism. It was as if we’d invaded Iraq and discovered there were no WMDs in the same few hours.

Chomsky and Herman wrote about how the elite reaction to America’s military loss in Vietnam was to create a revisionist history that not only steered us away from the reality of American crimes and policy failures, but set the stage for future invasions and occupations.

The post-Vietnam story blamed an “excess of democracy” for the loss, especially in the media:

Any real assessment of what happened would have focused on the fact that the campaign press had been so pompous for so long in telling voters what “presidential” meant, and in dictating fealty to crass stupidities like “nuance” and “the beer standard,” that voters entering 2016 were willing to cheer any pol with the insight to tell us to fuck off.

The subtext of all of this was that our rants about beer and “likability” and so on, were only the Washington press corps’ idea of what was important to a voter in flyover country.

Given that most actual voters were sunk in debt, working multiple jobs, uninsured, saddled with ruined credit scores, and often battling alcohol and opiate addiction and other problems, it was a horrific aristocratic insult to tell people each election cycle that what really mattered to them was what candidate looked most convincing carrying a rifle on...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Instead, the legend became that we hadn’t been obnoxious enough during the election season. What America really needed, the press barons decided, was a more directly didactic approach to who was and was not an appropriate political choice.

The Washington Post, for fuck’s sake, actually ran a Behind the Music–type feature about how it settled on its new “Democracy Dies in Darkness” slogan.

Sanders spoke of the divide between the public and elite institutions, of which the press was now clearly considered one.

“It’s not just the weakness of the Democratic Party and their dependency on the upper middle class, the wealthy, and living in a bubble,” he said. “It is a media where people turn on the television, they do not see a reflection of their lives. When they do, it is a caricature. Some idiot.”

Later, when colleagues on that same trip went after Kerry for reacting after Matt Drudge published an unsubstantiated rumor that Kerry had a mistress, I made the mistake of asking other reporters on the plane why we were giving this story life without first doing any work to see if it was true. Reporters took in the treacherous fact that I was doing a story on us with varying degrees of fury.

“This,” one reporter said to me, waving a hand across the press seats in the Kerry campaign plane, “is a fucking no-fly zone, dude.”

By 2012 I had a theory of the presidential campaign as a complex commercial process. On the plane, two businesses were going on in tandem. The candidates were raising money, which mostly entailed taking cash from big companies in exchange for policy promises. In the back, reporters were gunning for hits and ratings.

The candidate who most quickly found the middle ground between these two dynamics would become the nominee. Any candidate who was both good at raising money and deemed a suitable lead actor for the media’s campaign reality show—who was “likable” and “nuanced” but also not too “left” or “weak on defense” or espousing of “fringe” politics like Nader or Ron Paul—would be allowed to move on to the general.

In 2012, there was consternation among campaign reporters early on that it was going to be hard to “sell” the Obama-Romney general as suspenseful, since we all got the feeling that Obama would win easily.

This was not because of polls, but largely because of the same kinds of non-quantitative clues we would ignore in 2016: Obama’s events were uproarious and huge, whereas Romney struggled to pack halls even in his home state, and seemed to be every Republican’s third choice.

I went on CNN in the middle of that race and said aloud that reporters were pushing polls showing a close race just to rescue ratings. Despite the fact that many were saying this behind the scene...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Before long, we saw the remarkable phenomenon of Democrat-leaning pundits everywhere praising the absurdly maladroit Romney as a contender. The Independent called Obama “limp” (about the worst comment you get from a campaign reporter) and expressed shock that Obama wasn’t fighting harder against Romney, because anyone who has “seen him play pick-up basketball” knows “how competitive [Obama] is.” (You see how all of this idiocy ties together; as if one can actually glean anything from watching a politician play basketball!).

It was the ultimate demonstration of the Manufacturing Consent principle of a concocted, artificially narrowed public debate. We were meant to understand that the distance between Romney and Obama was vast, that much was at stake, and that the outcome was in doubt.

It turns out we let our electoral process devolve into something so fake and dysfunctional that any half-bright con man with the stones to try it could walk right through the front door and tear it to shreds on the first go.

When Trump talked about conspiracies of elites, he was not 100 percent wrong, and this was not going to change.