More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

little Jack stumbled out of the tent, dragging his blanket with him. It caught on a root and tore. Mom placed the coffee pot on the edge of the campfire. She sat on a stump, unraveled some yarn from the red potholder she had carried the coffee pot with, and she mended the blanket right on the spot.

Even more, it seemed to me, a picture of what Mom and Dad Carlson had been to me—to me and Jack—a stitch in the tear of our lives, holding us together, determined not to see us unravel.

Mothers are meant to stand over cribs and run their hands through the thick black hair of their newborn sons. Mothers are meant to tuck blankets around their baby boys and whisper, “I love you. I will see you in the morning.” A mother is not meant to stand over her son, asleep in a coffin, and say goodbye. But I have.

“Here,” she said, pressing into his hand a small collection of flour-dusted coins and dollar bills—currency that she had earned or found and hidden and saved. “Go and buy a rifle or more of your damn whiskey. But when this is gone, that’s all there is. And don’t you ever lay a finger on one of our children again.”

My mother often said that all a man has in this world—the only thing he’s born with, and the only thing he can take to the grave—is the dignity of being a human being. That is how she treated our father—with the dignity of being human. Even when she had to intervene to protect her children—for we too, she insisted, were human beings—she treated him as a man and not a monster.

“Well, Lottie’s a grown woman, Everett. She can make that decision for herself. But I will say this: We love Lottie. And we love that young Jack. They’re the only things we have left in this world to love and remind us of John. Nothing would delight us more than to know that you will love her and care for her—and that you will love and be a father to our grandson. And I know you would.”

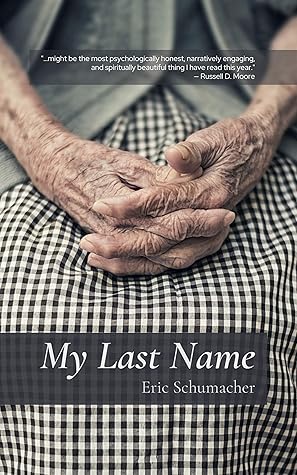

There is an oldness—and not a good oldness—that settles on a person, even a young person, when they have walked through seasons of grief and disappointment. There is a seriousness that settles on a person when they have felt the weight of loss and responsibility and worry. I felt that weight with John’s death, and I still felt that weight thinking of Jack’s future. I had become an old woman at the age of twenty-eight.

So he was young enough to marry an old woman like me. That is why our marriage worked: he could lead me through what another, younger man could not. And, I think, he helped me to become young again, even in my old age.