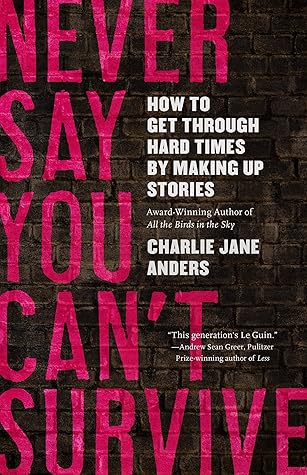

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 27 - August 8, 2022

Writing a horrifying story on your own terms means that you can show how someone can endure, or even triumph.

Imagination is always a form of resistance to domination and oppression, and we’ve all been saved by other people’s stories one time or another. There’s a reason why politicians and organizers try to tell stories, to put a human face on their policies, and worry about “controlling the narrative”—it’s because our world is built out of stories.

Normality is bullshit, and surrealist weirdness is a direct assault on the bullshit fortress.

a good fictional world has strong communities

We are shaped by our communities, for good and bad, and our communities define the worlds we belong to.

You have the power to shape worlds, and the monsters are scared of you.

A good character usually has as much story behind them as ahead of them. We might only need to glimpse their past, but we should know that they’ve already been on the journey before the story even begins.

The moment you wrote down a single word, you became a real writer. Really.

Nevertheless, rulemaking is another way that we internalize our anxieties, and then put them on everyone else. Nobody ever wants to admit how confused we all are.

The world is full of famous authors that you’ve never heard of.

None of us can do our best work unless we’re all supporting and encouraging each other, so you need to find the people who appreciate you and want to pull you up with them when they’re doing well.

Writing is one of the few areas where getting lost and confused can be liberating as well as terrifying.

When the whole world is on fire and the people you love are at risk, what should you write about? Whatever you feel able to write. Whatever will make you feel like you can keep living and fighting. Write the thing that you’re ready and excited to write—not the thing that you feel the moment calls for, or the story that you think will fix every broken thing in the world. Your job is to survive, and maybe to help others to survive. That’s it. That’s more than plenty.

We’re all trapped inside history and we can’t see the outlines from where we are.

The best thing to write during a slow-motion tragedy is the thing that strengthens and amplifies your own perspective. Because there’s nothing more badass and defiant than insisting that your stories matter, and that your experiences and concerns are important. In the end, that’s how we make it to the other side: by bringing all of ourselves into our writing.

Every writer is also an actor.

Suspension of disbelief is just as important when you’re writing as when you’re reading—or maybe even more so.

Every character needs goals or desires—and they don’t have to be related to the plot. In fact, I often find that a character who’s chasing after something unrelated to the search for a plot widget is more interesting.

Because I’m a person writing about people, it’s impossible to plan everything—but it’s also impossible to get anywhere unless I’m making some plans and thinking ahead.

So if your plot is a machine, it’s a rocket: it needs to keep accelerating in order to achieve escape velocity. And it needs to keep the people inside it alive, rather than letting that acceleration smush them to death.

Especially in a first draft, it’s pretty normal to feel like you’re pulling your punches, even at the best of times.

When something good happens to a character, we all demand a high level of plausibility. Happy events must be “earned.” Meanwhile, we require much less explanation when the world goes pear-shaped. Because when bad things happen, that’s “realism.”

At some point, we all started to think of violence and misery as the point of storytelling, rather than as a means to an end. Many writers (myself very much included) gloated endlessly about how much we love to “torture” our characters.

We started to treat ugliness as a key signifier of quality, rather than just one valid creative choice among many.

I increasingly find it helpful to think in terms of “options become constrained,” rather than “things get worse.” It’s not so much that the situation deteriorates—it’s more like doors are slamming shut, and the protagonists have fewer and fewer courses of action open to them. The rising sense of desperation is the most important thing, and there are a million ways to get there that don’t risk making you more upset when the world is already upsetting enough.

the best ending is the one that serves your characters best. They’ve been on a journey, and they’ve arrived, and they’ll never be the same again. And they do something, or experience something, that lets us know how their voyage has transformed them, and maybe moved them closer to figuring themselves out.

Seven words sum up a really good landing: “Nothing will ever be the same again.” A powerful work of art usually leaves you feeling like the characters, and maybe even the world, have gone through some changes, and there’s no going back to the way things were before.

fiction writing is one of the few areas in life where you can change the question to fit the answer.

Unexpected but inevitable: that’s the balance that most endings need to strike.

If you can get mad, you’ll never run out of stories.

You can absolutely be angry, and yet write a story that’s not an angry story at all.

Anger is like a primary color of emotion. If you can summon anger, you can write anything.

During those times when I’ve been really messed up by things that have happened to me—or by the state of the world—I’ve found that I’ve had more rage than I knew what to do with. So I channeled that rage into writing about people rising up, fighting back, doing the right thing, and this reminded me that I have more power than I realize. That together, we can tear down monuments and take down wannabe strongmen. And screw anybody who wants to police your anger.

Often as not, when I have a character who’s not clicking, it’s because I haven’t found what they’re angry about yet.

I don’t write characters. I write relationships.

the best relationship to focus on is usually the one that brings out something unexpected in one or both characters.

Your characters’ desires don’t have to be reasonable or fair—in fact, it’s often better if their goal is something we know they can’t, or shouldn’t, attain.

The bigger the emotion you’re trying to evoke, the more attention you need to pay to the smallest things. This is true in two different ways: each moment needs to be grounded in real sensory details, and there need to be small clues and barely noticeable moments leading up to a huge emotional climax.

History has a way of rewriting fiction without changing a word, which is why we talk so much about stories that have aged badly.

“All stories are political” is another way of saying, “All stories are about people living in society.” And that means that the more real and messy you can make both the people and the society, the sharper the politics will be.

Communities don’t just make world-building richer. They also provide allies, and motivation, in the struggle to make things fairer. They’re what we fight for, and how we fight for it.

you never really finish building a world.

I feel most enchanted by writing when I’m thinking deeply about the meaning of something I’m writing, and why I’m choosing to write this thing, instead of something else.

Recognize that “strange” doesn’t have to mean “ugly.”

We all need to populate our worlds with people from many backgrounds, genders, sexualities, and disability statuses, without trying to tell the stories that aren’t ours to tell.

your writing style is a nice snuggly blanket, embroidered with pretty flowers, that will keep you safe and warm when the world is a cold and inhospitable place. You may start singing to yourself, in a soft voice, while you’re wrapped in that blanket, and that song, too, is part of your writing style. Your distinctive use of words and phrases—your voice—can be a very reassuring thing to nurture in yourself.

Different people will have different ideas about what a “good” writing style looks like.

Writing is the only machine where there is no distinction between gears and ornamentation. Everything you put on the page is doing work and (hopefully) looking pretty. Looking pretty will make the work go better, and vice versa.

If there’s any way to misread a sentence, you can be sure it will happen. The only solution I’ve found is to reread slowly and think about how to make it obvious which words are the subject, verb, and object in each sentence. And reading sentences out loud is always a valuable diagnostic, with or without an audience.

write the book that only you could have written.