More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

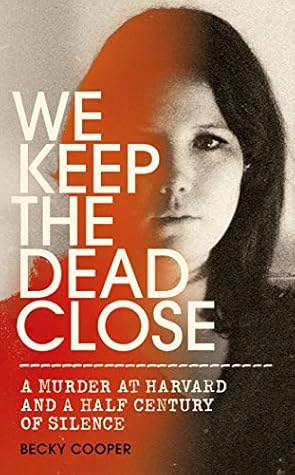

by

Becky Cooper

Read between

December 9 - December 22, 2024

It wouldn’t be surprising if an institution that prided itself on being older than the US government might have behaved as though it were accountable only to itself.

The way I saw it, either Harvard had covered up a murder and was allowing a killer to remain on faculty, or we were imprisoning an innocent man with our stories.

“The colonial aspect is still very much with us,” Karl continued, bringing us up to the present. His enunciation underlined his words: These rich nations—England, France, Germany—went in and plundered other nations, collecting their past and controlling it, by being the ones to interpret it, to give it significance and meaning. “Archaeology is the handmaiden of colonialism.

It was unique, Karl explained, because people settled there permanently before the invention of agriculture in the Levant. In other words, it wasn’t the need to tend crops and to raise animals that led these people to give up their nomadic ways. It was complex ritual beliefs, he said, as exhibited by one particular pattern of behavior: They buried the dead under their houses.

It struck me then that the way we relate to our dead is the oldest mark of our humanity. “The dead are kept close to you,” he said. I circled it in my notebook.

The people who let us believe for a moment that we weren’t truly alone and then pulled the promises away. I could feel that as we circled the room, we were trying to protect each other from all that haunted us, the invisible burdens that laced our every interaction.

The dean of Radcliffe gave a talk about how we choose to forget aspects of the past in order to forge a collective identity. She called this cultural amnesia.

And as I tried to own this power, I discovered, as perhaps Jane did, that this trailblazing did nothing to supplant the need for companionship. In fact, it only made the search harder, and the need greater.

I didn’t explain that I wanted an active love: loving someone for something rather than for the removal of a fear—of never being known, of never being able to get the timing right. I didn’t say that taking shelter in someone else’s loneliness was no longer enough. And I certainly didn’t admit—to myself, never mind to him—that Jane had taken his place in keeping me company.

The best story? That’s the truth.”

They are produced within the context of a long past world, recovered as objects within our present world, and offered an interpretation, or a ‘meaning,’ which may, or may not belong to either world.” In short, Karl wrote, ‘All archaeology is the re-enactment of past thoughts in the archaeologist’s own mind.”

Karl really was guilty and brazenly taunted people with his invincibility. He was innocent and both courted and crafted his reputation as a suspected villain. Or, of course, the third possibility: I was the one trapped in a game of symbols of my own invention, finding meaning where there was none to be found.

The historical gaze is inextricable from the biases of the historian. Even if we think we’re uncovering the past, what we are really doing is reconstructing it, adding our own flesh to old bones.

The reckless hedonism they’re able to pull off makes me sad that the universe wasn’t as lenient with Jane.

Is it ever justifiable, I wondered, to trap someone in a story that robs them of their truth, but voices someone else’s?

that even if the members of a system were good people, the system to which they belonged could still be destructive.

“It’s hard to admit you belong to the world you’re studying.”

These are the whisper networks; these are the stories that get swapped in the field and passed quietly between graduate students. Their job is to limit outlier behavior and to keep members of the community safe when what can be said out loud is constrained.

Gossip, in other words, is punishment for people who move outside the norm.

“The one thing I miss, or never got enough of, is a rare and precious quality in a relationship, and that’s tenderness. A trust, a feeling that nothing is a threat. The feeling that no demands are being made. There are no expectations. You like it the way it is.”

Not only did it serve as a narrative check on someone with power, like Karl, who was seen as transgressing, it was also a way of cautioning against promiscuous, assertive behavior from someone in Jane’s position: a female graduate student.

It felt like he was teasing me with the notion that any set of facts could conform to any narrative, if you chose to arrange it a certain way.