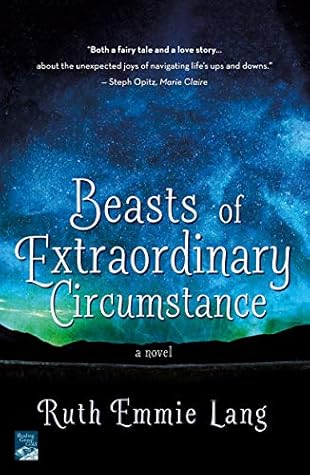

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I could tell, even before he spoke, that he had drained his mind of his own sadness and replaced it with empathy for mine. “I’m really sorry,” he said, and meant it.

“This is where I come when I’m sad … or happy. It’s where I come to feel is what I mean.”

“I feel like … before, I had one way of looking at things, and now, I have a million possibilities, and I get to choose.”

Sometimes it takes hearing your own words from another person’s mouth to realize how strange they sound.

Her flaws were in plain sight, not buffed out with salt scrubs or hidden under layers of Mary Kay.

All I could hear was the hiss of air between two people who had nothing more to say to each other.

He sighed disdainfully as he threw his man-purse on the kitchen table, but I barely even noticed.

“Why do you do that?” “Do what?” “Take something beautiful and vandalize it with skepticism?”

Never before had my incompetence been so hard to ignore. It was usually the kind of incompetence that got drunk and napped in places it shouldn’t, not the kind that flooded city streets and downed power lines.

“The worst part of it is I don’t remember anything about that day. How do you not remember the worst day of your life? How do you not remember what you were doing? How you were feeling? I think about that day and all I see is white.”

Forgive me for both my coming and going.

Weylyn hesitated, as if he was deciding between telling the truth and telling me what he thought I wanted to hear. “It’s a long story,” he said, choosing neither.

Giggling girls usually meant one of two things: either they liked you or they thought you were stupid. It was impossible to tell the difference.

Stealing food was how my friends and I displayed dominance over each other. The less of an appetite you had at the end of the school day, the stronger you were.

And like a frat, the boys were constantly fighting, stuff was always getting broken, they threw up and peed the bed and passed out on the floor. In some ways, it was scarier than a frat because their behavior didn’t require a single drop of alcohol.

I wanted to tell him to stop worrying because our Amish neighbors didn’t care about him enough to plot against him, but I think the paranoia made him feel important in a world that said he wasn’t. Why do you have to believe that the government mistakenly put you on the terrorist watch list for you to feel good about yourself? I wanted to say. You’re important to me. Isn’t that enough? Instead, I occasionally told him I heard a clicking noise during a call so he could think maybe someone had bugged the phones.

I didn’t know where he had been those last fifteen years, but he looked forgotten, like a pressed flower in the pages of a book.

“Don’t leave anything you can’t come back to.” I know I can come back here and I will be welcomed, and that brings me more comfort than anything else in this world.