More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

May 5 - May 5, 2022

helped me see the limitations of restorative justice—that it often meant restoring conditions that were fundamentally harmful and unequal, unjust. If the racialized system of capitalism has produced such inequality that someone is hungry and steals a purse to resource a meal, returning the purse with an apology or community service does nothing to address that hunger.

In the longest term vision I can see, when we, made of the same miraculous material and temporary limitations as the systems we are born into, inevitably disagree, or cause harm, we will respond not with rejection, exile, or public shaming, but with clear naming of harm; education around intention, impact, and pattern breaking; satisfying apologies and consequences; new agreements and trustworthy boundaries; and lifelong healing resources for all involved.

Right now, call outs are being used not just as a necessary consequence for those wielding power to cause harm or enact abuse, but to shame and humiliate people in the wake of misunderstandings, contradictions, conflicts, and mistakes.

We don’t have a collective clarity about the distinctions between conflict, harm, or abuse, but online, we seem to respond to all of it with the same energy—consistently punitive, too often joyful.

Which isn’t to say that a public accounting of harm, and consequences, isn’t necessarily the correct move. In cases of rape, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and abuse, the callout can be the only move that stops the immediate harm without engaging the state. Shaming behaviors of abuse in a culture where they have been normalized is, and has been, a necessary survival technology.

The first and biggest thing is that call outs never feel powerful to me as a move to resolve conflict, especially when that conflict is unveiled without the consent of both or all parties in the dispute. Call outs don’t work for addressing misunderstandings, issuing critiques, or resolving contradiction. Call outs feel most powerful when they are used with their tactical intention—for those with less positional, political, economic, or other power to demand accountability to stop harm or abuse.

Is the only acceptable consequence to those making the call out for the accused to cease to exist?

we want to distance ourselves from those who cause harm, and we are steeped in a punitive culture, which, right now, is normalizing a methodology of “punish first, ask questions later.” And, because we are in the age of social media, we now have a way to practice very publicly.

This is not a case against call outs. There is absolutely a need for certain call outs—when power is greatly imbalanced and efforts have been made to stop ongoing harm, when someone accused of harm won’t participate in community accountability processes or honor requested boundaries, the call out is a way of pulling an emergency brake.

I can’t help but wonder who benefits from movements that engage in public infighting, blame, shame, and knee-jerk call outs? I can’t help but see the state grinning, gathering all the data it needs, watching us weaken ourselves. Meanwhile, the conflicts are unresolved, and/or harm continues.

Knee-jerk call outs say: those who cause harm or mess up or disagree with us cannot change and cannot belong. They must be eradicated. The bad things in the world cannot change, we must disappear the bad until there is only good left. But one layer under that, what I hear is: We cannot change. We do not believe we can create compelling pathways from being harm doers to being healed, to growing.

That we can act towards accountability with the touch of love. That when someone falls behind, we can use a parent’s voice of discipline, while also picking them up and carrying them for a while if needed. I want us to adapt from systems of oppression and punishment to systems of uplifting and transforming.

I have noticed that at the most basic level, I feel better about myself because I’m on the right side of history…or at least the news cycle. But lately, as the attacks grow faster and more vicious, I wonder: is this what we’re here for? To cultivate a fear-based adherence to reductive common values? What can this lead to in an imperfect world full of sloppy, complex humans? Is it possible we will call each other out until there’s no one left beside us?

Sometimes this was because the takedown wouldn’t have had the impact I wanted; destroying a person doesn’t destroy all of the systems that allow harmful people to do harm. These takedowns make it seem as if massive problems are determined at an individual level, as if these individuals set a course as children to become abusers, misogynists, racists, liars.

That’s because the answers rehumanize those we feel are perpetrating against us. “Why?” often leads us to grief, abuse, trauma, often undiagnosed mental illnesses like depression or bipolar disorder, difference, socialization, childhood, scarcity, loneliness. Also, “Why?” makes it impossible to ignore that we might be capable of a similar transgression in similar circumstances. We don’t want to see that. Demonizing is more efficient than relinquishing our world views, which is why we have slavery, holocausts, lynchings, and witch trials in our short human history.

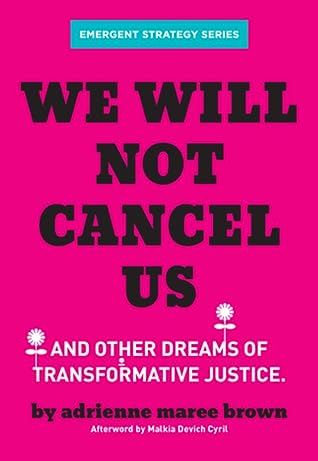

We will not cancel us. If we give up this strategy, we will learn together the other strategies that will ultimately help us break these cycles, liberate future generations from the burden of our shared and private pain, leaving nothing unspeakable in our bones, no shame in our dirt. Each of us is precious. We, together, must break every cycle that makes us forget this.