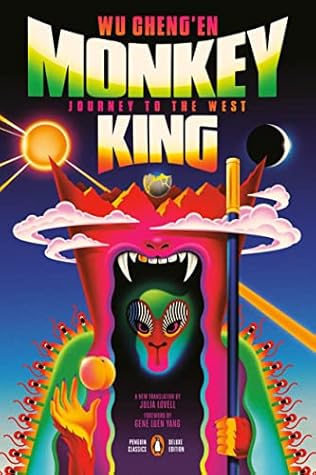

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In addition to Journey to the West, another three of the six “master novels” of imperial China were completed during the Ming dynasty: The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a recounting of the civil war into which China plunged after the fall of the Han dynasty in AD 220; The Water Margin, a picaresque tale of twelfth-century outlaws; and The Plum in the Golden Vase, a sexually explicit chronicle of intrigue in a wealthy Ming household.

(In Chinese literary culture, religion, and folklore, the monkey is often the playful or cunning shadow of human character, though it is also capable of great devotion and piety.9)

The fundamental objective of the quest is to train and steady Monkey’s mind through the vicissitudes of the journey.

“Our great king’s new sense of mortality suggests the beginnings of a religious calling. Only three types of creature can escape King Yama and his wheel of life and death: Buddhas, immortals, and holy sages.”

“Even if my quest takes me to the very end of the world, I will return with the secret of eternal life.”

Monkey remained determined to seek the formula for eternal life, while the humans who surrounded him sought only money and fame, without a thought for their own mortality; no one cared what became of him.

As you fall into the tenth, ‘awoken,’ wu, I will call you Sun Wukong: Sun-who-has-awoken-to-emptiness.

The name spoke an important truth: for at the beginning of everything, there were no names—only emptiness. To advance from emptiness, living creatures must first become aware of it.

“Nothing in this world is hard. It is only the mind that makes it so.”

The active mind conjures up demons; the stilled mind extinguishes them.