More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

When I was growing up in Scotland, World War II still cast a long shadow. Sugar rationing did not end until 1953, meat rationing until 1954.

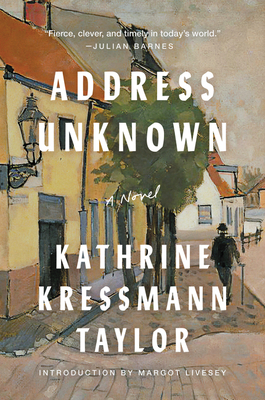

Novelists can count on readers to know, in some detail, the main facts of the war and can shine a light on some new aspect of the struggle, as happens in Mamta Chaudhry’s Haunting Paris, Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, Walter Kempowski’s All for Nothing, Ian McEwan’s Atonement and Jim Shepard’s The Book of Aron, to name a few. These novelists are looking back, fully aware of the dramatic ironies. But Kathrine Kressmann Taylor’s Address Unknown is not a historical novel.

The rapturous reception the novel received when it was published in 1938,

I read Address Unknown in November 2020, and I have been thinking about it ever since.

Address Unknown has this Janus-like quality. The novel consists entirely of letters (and one cablegram) written between two German friends, Max Eisenstein and Martin Schulse, who own a successful art gallery in San Francisco.

Why does a good person become a bad person? What power does a citizen have against the state?

One of the signal advantages of the form is that it banishes the narrator’s voice and moral stance; the letters represent only the point of view of the characters. It also allows for a useful compression. Readers

The voices of the two friends are pleasingly distinct – Max in San Francisco a little more colloquial, Martin in Munich a little more formal – but at the beginning of the novel they seem united in their attitudes. Max describes himself as selling the paintings Martin is sending over from Germany ‘at an appalling profit’ and delights in getting an indecent price for an ugly Madonna from old Mrs Fleshman. ‘You speak of the poverty there’, he writes. ‘Conditions have been bad here this winter, but of course we have known nothing of the privations you see in Germany.’ From the thirty-room house

...more

few years after Address Unknown appeared, she went on to write a second novel, Day of No Return.

In her introduction, Kressmann Taylor describes Hitler’s plan to have the powerful church become a tool to disseminate Nazi doctrine. The Nazis succeed in taking over the church, ‘but gradually,’ she writes, ‘they became aware that something was wrong. . . . A

force was resisting them, something they could not put their hands on – a belief.’ The

You go to a democratic Germany, a land with a deep culture and the beginnings of a fine political freedom. It will be a good life.

The business continues to go well. Mrs Levine has bought the small Picasso at our price, for which I congratulate myself, and

Besides they probably never entirely trust another Jew.

There is no bitterness left there, for that passes quickly when one is young as she is. A few years and there is only a memory of the hurt, and of course neither of you was to be blamed. Those things are like quick storms, for a moment you are drenched and blasted, and you are so wholly helpless before them. But then the sun comes, and although you have neither quite forgotten, there remains only gentleness and no sorrow.

Fourteen years since the war!

A gentle, brave soul is in her dark eyes, but there is something strong as iron and very daring too. She is a woman who does nothing and gives nothing lightly.

Yet for Griselle I keep a tenderness that will last long after she has taken a much younger man for husband or lover. The old wound has healed but the scar throbs at times, my friend.

Elsa, too, knows nothing of the old feeling between us and you know with what warmth she would welcome your sister, as she would welcome you.

What a fine climax for two men of forty! Is it for this we spend our lives, to scheme for money and then to strut it publicly?

We are vain and we are dishonest because it is necessary to triumph over other vain and dishonest persons. If

But there is another realm where we can always find something true, the fireside of a friend, where we shed our little conceits and find warmth and understanding, where small selfishnesses are impossible and where wine and books and talk give a different meaning to existence. There we have made something that no falseness can touch. We are at home. Who is this Adolf Hitler who seems rising toward power in Germany? I do not like what I read of him.

I tell you truly, Max, I think in many ways Hitler is good for Germany, but I am not sure.

The man is like an electric shock, strong as only a great orator and a zealot

A leader is found! Yet cautiously to myself I ask, a leader to where? Despair overthrown often turns us in mad directions.

That is the name for Herr Hitler’s party. But also it is not only expedient, there is something more, a feeling that we of Germany have found our destiny and that the future sweeps toward us in an overwhelming wave. We too must move.

The quicksand of despair held them, it was at their chins. Then just before they died a man came and pulled them out. All they now know is, they will not die. They are in hysteria of deliverance, almost they worship him. But whoever the savior was, they would have done the same. God grant it is a true leader and no black angel they follow so joyously. To you alone, Max, I say I do not know. I do not know. Yet I hope.

It is impossible for me to be in correspondence with a Jew even if it were not that I have an official position to maintain.

The Jewish race is a sore spot to any nation that harbors it. I have never hated the individual Jew – yourself I have always cherished as a friend, but you will know that I speak in all honesty when I say I have loved you, not because of your race but in spite of it.

The Jew is the universal scapegoat. This does not happen without reason, and it is not the old superstition about ‘Christ-killers’ that makes them distrusted. But this Jew trouble is only an incident. Something bigger is happening.

You will see only that your own people are troubled. You will not see that a few must suffer for the millions to be saved. You will be a Jew first and wail for your people. This

You lament but you are never brave enough to fight back. That is why there are pogroms.

is so unlike you I can only attribute its contents to your fear of the censorship.

You are a liberal,

Martin. You have always taken the long view.

me. I did not expect you would take up arms for my people because they are my people, but because you were a man who loved justice.

shortly. My second letter was more encouragement than warning, and it has been returned to me, the envelope unopened, marked only addressee unknown, (Adressat Unbekannt).

All this they tell me in two words, Adressat Unbekannt.

Heil Hitler! I much regret that I have bad news for you. Your sister is dead. Unfortunately she was, as you have said, very much a fool. Not quite a week ago she came here, with a bunch of stormtroopers right behind her.

duty. She has displayed her Jewish body on the stage before pure young German men. I should hold her and turn her over to the stormtroopers. But this I cannot do.

tired. She does not run very fast and the stormtroopers have caught sight of her. I am helpless. I go in the house and in a few minutes she stops screaming, and in the morning I have the body sent down to the village for burial.

In 1939, Simon & Schuster published Address Unknown as a book and sold 50,000 copies

He and Elliott decided that the story was ‘too strong to appear under the name of a woman’, and assigned Kathrine the literary pseudonym ‘Kressmann Taylor’, a professional name she accepted and kept for the rest of her life, largely because of the success of Address Unknown. This is how she describes the original motivation for the story:

A short time before the war, some cultivated, intellectual, warm-hearted German friends of mine returned to Germany after living in the United States. In a very short time they turned into sworn Nazis. They refused to listen to the slightest criticism about Hitler. During a return visit to California, they met an old dear friend of theirs on the street, who had been very close to them and who was a Jew. They did not speak to him. They turned their backs on him when he held his hands out to embrace them. How can such a thing happen? I wondered. What changed their hearts so? What steps brought

...more

fine. Even Charles Lindbergh came back from Germany saying how wonderful the people were. But there were some students who returned from studying in

‘Stop it. We’re in danger. These people don’t fool around. You could murder one of these Nazis by writing letters to him.’

I wanted to write about what the Nazis were doing and show the American public what happens to real, living people swept up in a warped ideology.

Italy, where she experienced the great flood of the Arno river in November of that year which inspired her third book, Diary of Florence in Flood, published to critical acclaim in both England and America the following spring.