More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

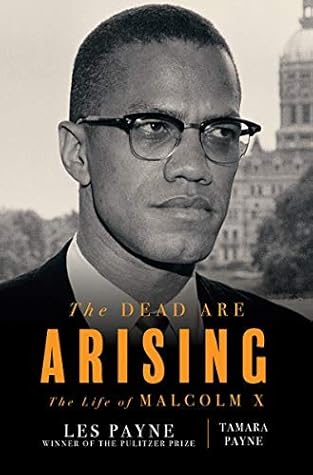

by

Les Payne

Read between

February 5 - February 20, 2021

A notorious former Methodist preacher, one William J. Simmons, retreated to Stone Mountain, Georgia, with at least fifteen other local firebrands, including the speaker of the Georgia legislature. Simmons, the son of a physician who had been a leader of the original Alabama Klan of the 1860s, presided over a squad of men shivering before a burning cross of pine boards. They placed a Bible on a jutting rock altar, along with an American flag, a canteen of water, and a sword, over which they swore allegiance to wage an armed campaign against Negroes seeking rights as full citizens of the United

...more

With its largest klaverns outside the South in Indiana, Colorado, and Michigan, the national organization claimed a membership of some 3 million that included sheriffs, cops, district attorneys, mayors, and at least two sitting governors, not to mention hundreds of thousands of women.

At the height of its political power, the Klan flexed its muscle when some forty thousand white-robed men and women waved American flags and proudly paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue in the nation’s capital as onlookers cheered on August 8, 1925—a few months after local KKK vigilantes had terrorized Malcolm’s pregnant mother, Louise.

Already, some two generations out of slavery, when statistically they had been three-fifths of a person, “Negroes” conducted an unrequited love affair with the republic that had, reluctantly at best, freed them in 1863. They fought in U.S. wars and paid taxes. They rendered cheap labor on railroads and docks, in factories, private kitchens, and cotton fields. Although fulfilling the obligations of citizenship, Negroes were systematically denied the benefits.

Negroes were repressed as a permanent underclass and were flagrantly denied equal access to housing, jobs, education, public accommodations, due process in the courts, and, despite the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, the guaranteed right to vote. Even when American women were granted the vote in 1920, Negroes across gender lines were largely denied the franchise, especially in the South, where some 80 percent of them lived.

When, as previously mentioned, William Monroe Trotter, the editor of the widely read Negro newspaper the Boston Guardian, took a delegation of Negro leaders to the White House to protest this segregated federal policy, President Wilson rebuffed them sharply. “Segregation is not humiliating, but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen,” President Wilson told the delegation from the National Independent Equal Rights League during its November 12, 1914, visit.

“Your manner offends me,” Wilson muttered.5

“As your skin gets lighter, your future gets brighter” became a guideline of this prejudice, which, despite periodic ebbs, would survive into the twenty-first century.

Garvey boomed, “The United Negro Improvement Association is carrying out just what the Ku Klux Klan is carrying out—the purity of the white race down South—and we are going to carry out the purity of the black race not only down South, but all through the world.”

“We wish liberty,” Garvey said in this July speech. “We wish to be good American citizens; we want to be President of the United States; we wish to be Congressmen; we wish to be Senators; we wish to be governors of states; we wish to be mayors of cities; we wish to be police commissioners. It is a wish, all right, but the other [white] fellow wishes the same thing. Now, is he going to allow you to have your wish?”

The Negro “shall never be [president, governor, mayor, etc.] as long as there is one white man living in the United States of America,” Imperial Kleagle Clarke responded, according to Garvey.

The UNIA leader, of course, could not imagine that, generations later, blacks in America would overcome what appeared to be insurmountable odds.

key Garvey credo: “Liberate the minds of men and ultimately you will liberate the bodies of men.”

“Our attitude made a difference in how they dealt with us compared to some of the others [Negroes],” said Wilfred. “When white people find out that you don’t have that inferiority complex, they deal with you at that level; it makes a difference. A lot of our problems we bring on ourselves by our own inferiority feelings sometimes. If you acted like you were inferior, that’s the way they related to you. If you didn’t act like you were inferior, then they would be forced to treat you as an equal. And this is the way we were.”

And he would rattle off a string of naughty pickup lines, such as “I’m not the plumber or the plumber’s son, but I can fill your hole until the plumber comes.”

Racial exclusion from the mainstream economy, he later reasoned, meant that “almost everyone in Harlem needed some kind of hustle to survive, and needed to stay high in some way to forget what they had to do to survive. . . . In one sense, we were huddled in there, bonded together in seeking security and warmth, and comfort from each other, and we didn’t know it. All of us—who might have probed space, or cured cancer, or built industries—were, instead black victims of the white man’s America social system.” 32 Such analyses would come later.

Wright wrote in his autobiographical Black Boy, recalling his thoughts upon first reading A Book of Prefaces. “I pictured [Mencken] as a raging demon, slashing with his pen. . . . He was using words as weapons, could words be used as weapons? Well, yes, for here they were. Then, maybe, perhaps, I could use them as weapons.” 12

as a result of early Hollywood films, U.S. government propaganda, white Christian missionary reports, newspaper coverage, and overall societal conditioning, many Negroes in the early twentieth century looked down upon Africa as a pariah “dark continent” of unspeakable embarrassments.

Both Philbert and Reginald, as described earlier, had written to Malcolm in Concord Reformatory in 1947, urging him to join the “natural religion for the black man.” But they could not include a lot of detail, for they knew letters were being read by prison authorities. Malcolm was interested, according to Wilfred, but had a problem accepting that ‘“the white man is a devil.’ That was a problem for him. He couldn’t accept that.” 4

eventually Malcolm realized that maybe this white man could be the devil.”

he joined the prison’s weekly debate team and cultivated world-class polemical skills during face-offs in Norfolk prison with debating teams from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Yale, and Harvard. These verbal calisthenics with Ivy League wordsmiths pumped up Malcolm’s dialectical prowess as a fierce and fearsome debater, a skill that would power his meteoric rise as a Muslim advocate in Harlem, New England, and the rest of the United States—and eventually the world—while also incurring envy within the Nation of Islam.

Malcolm’s behavior in prison began to prefigure, and to prepare him for, his role as the Nation of Islam’s most gifted and successful proselytizer and demander of justice. After converting several other inmates to his newly embraced religion, he started agitating for Muslim religious rights in prison, such as food that met dietary restrictions and cells that faced east to facilitate prayer.

Between 1882 and 1946, according to the Negro Yearbook, a minimum of 3,425 blacks were documented as having been lynched in America, a rate of more than one incident a week.

‘no man is a hero to his valet,’” Malcolm wrote in the Autobiography.

His was an aggressive, macho approach, and he disparaged the nonviolent stance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as cowardice pure and simple.

Muslim’s self-defense strategy demanded that if attacked, the Fruit of Islam, the Nation’s security force, would not beg and crawl but would take “a life for a life.”

Malcolm emphasized furthermore that if a Muslim adhered strictly to the teachings and discipline of the sect, Allah would not allow anyone, or anything—not even a weapon—to harm the believer.

While we were members of the Christian church, we were rejected by the segregated churches of our slave masters . . . no one wanted us, we didn’t even want ourselves.1

Malcolm flatly dismissed all chances of human postmortem reward, proclaiming that there would be “no Heaven beyond the grave.” A few in the audience gasped. American Negroes, “the lost sheep,” Malcolm thundered, would progress only when they forsook the Christian yearning for the hereafter and devote themselves to Muslim concerns for the right-down here and now.

Elijah Muhammad’s followers were viewed as humorless, bow-tie-wearing “Black Mooselim” carpetbaggers from the North. They rejected Jesus Christ; didn’t believe in heaven or hell; and, most unforgiving to Negro sensibilities, didn’t permit music during worship services.

On election day, Negroes flocked to the polls and voted overwhelmingly for the junior senator from Massachusetts. In the previous presidential election, in 1956, about 60 percent of their vote had gone to the incumbent Republican, Dwight Eisenhower. This time, 70 percent of Negroes voted for Senator Kennedy—a decisive margin in five states—and helped provide him the slimmest popular vote margin of any president in the twentieth century: 118,000 votes out of more than 68 million cast, a winning margin of 0.17 percent. The abrupt switch was nothing less than historic, with implications that

...more

The Klan turned the Kennedy victory into a membership boon: by the time of JFK’s inauguration in January 1961, the KKK had doubled its sworn-in, dues-paying membership, to around twenty thousand, since March of the previous year.

Not only did Negroes have every human right to despise their powerful tormentors, Malcolm said, they also had the right to defend themselves against a barbarism that knew no bounds. Such counterrejection, at least in the short term, some psychiatrists have agreed, may well serve as an antidote to induced group self-loathing.

The cagey Messenger avoided any public resort to bloodletting across the color line, except to state that in some vague and distant future “war is inevitable between blacks and whites.” No traceable order, direct or otherwise, was ever issued for spilling the blood of the “blue-eyed devils.” Malcolm, on the other hand, slyly left violence against whites on the table.

miscegenation—more specifically, sex between a white woman and a black man—had emerged as the primal fear triggering the white knights’ decades-long lynching bee, which had killed thousands of Negroes.

Sex between black men and white women, Malcolm preached, was the white man’s greatest nightmare. He took pains to note the fact that Southern white men had been fathering children by black women, almost as a matter of course, since the days of slavery. This particular version of miscegenation was never cited as a sin against God.

The root of segregation, if not of racism itself, at one level rested upon the white South’s perception of a need to prevent the procreative coupling of white women and black men at all cost. At another level, of course, segregation allowed the dominant white group, with access to national power, to deprive Negroes of their fair share of economic resources needed to reap the full benefits of citizenship.

Segregation, Malcolm maintained, was not ordained by God but created by white men.

“The South to blacks means south of Canada.”

James Adams, then the assistant FBI deputy director, told the Senate committee that the Bureau had discovered approximately twenty-five incidents of harassment of King by Hoover’s agents for which there was no “statutory basis or justification.”

“The last bulwark of capitalism today is America,” he told a New York audience in May, when he was just back from his hajj. “It’s impossible for a white person to believe in capitalism and not believe in racism. You can’t have capitalism without racism.” If you meet a non-racist white, he added, “usually they’re socialists.”

An old African proverb states: ‘Educate a man and you educate an individual; educate a woman and you educate an entire family.’”

At its core, Malcolm’s message spoke to people of every rank: white people are not superior, and black people are not inferior. While black people have been conditioned by generations of oppression to feel a false sense of inferiority, Malcolm’s core messaging provides tools to move from this self-loathing to self-acceptance with the hope of redirecting oppressed people’s energy toward self-determination and community success. He reframed the oppression of black Americans from a civil rights issue to a human rights issue.

“You can’t hate the roots of a tree and not the tree,” he would say as he directed African American eyes toward Africa. “You can’t hate Africa and not hate yourself.”

Malcolm’s political organization was not as durable, especially in the ominous climate that surrounded his assassination. Without his inspirational presence, and faced with the cloud of police investigations and death threats, many of Malcolm’s followers dispersed, and his infant organizations, Muslim Mosque, Inc., and the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), faded into obscurity.

Many Nation members, including Muhammad Ali, followed their imam into orthodoxy. But not all did. Most notably, the powerful minister Louis Farrakhan (Louis X), who had been Malcolm’s protégé before becoming his enemy, quit the group in 1977 and began resurrecting the old Nation of Islam, using the doctrines Elijah Muhammad had preached. Since then, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan has continued to lead this reconstituted Nation of Islam.

As a Black American I do feel that my first responsibility is to my 22 million fellow Black Americans who suffer the same indignities because of their colour as I do. I don’t believe my own personal problem is ever solved until the problem is solved for all 22 million of us.

In every Middle-East or African country I have visited, I noticed the country is as “advanced” as its women are, or as backward as its women. By this I mean, in areas where the women have been pushed into the back-ground and kept without education, the whole area or country is just as backward, uneducated and “underdeveloped.” Where the women are encouraged to get education and play a more active role in the all-around affairs of the community and the country the entire people are more active, more enlightened and more progressive. Thus, in my opinion, the Muslim religious leaders of today

...more