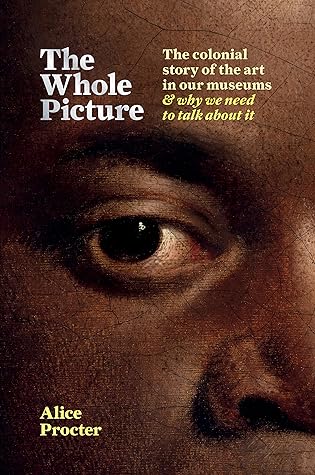

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 27 - March 23, 2022

The way we look at things is never objective: it is shaped by who we are, the experiences we bring with us, the ways we have been taught to see the world. No two people look at art in exactly the same way.

The collecting process always involves an element of appropriation: that is to say, the act of taking an object out of its context and placing it into a new one.

The whole idea of ‘saving’ a painting for a national collection sits awkwardly, when at the same time many museums are attempting to justify keeping objects from other cultures that are sought for repatriation. It is a double standard, implying that some communities have more rights to their material histories than others.

The English word ‘loot’ actually comes from the Hindi lūt, meaning ‘spoils of war’: it was first recorded in Company vernacular in 1788 (and came into more common usage in England by the 1850s), which gives a hint of the prevalence of looting at the time.

there are artists who have merchandised their work, and there is nothing wrong with that. Where it gets messy is the question of consent and power: who has the right to choose how an object is commercialized?

The definition of ‘historically significant’ moves over time: that does not mean these portraits should not be on display or deserve to be forgotten, but it does mean there will always be people who were not considered worthy of depiction in their lifetimes, and whose significance has only been recognized later (if at all).

When we look back at historical episodes, and especially social justice movements, it is too easy to see moments in isolation, and to want to identify dramatic turning points. We lose sight of the slow, determined action that always comes before a change; the decades of organizing before the moment of transformation.

Arguably, the history of slavery is both the most discussed and least visible element of British imperialism: it is present in the history curriculum as a possible (but not required) subject for students aged 11 to 14, and it is widely represented in popular culture, though most of these representations tend to be from the USA. But there is a pervasive sense that it is something that happened elsewhere,

the danger with specialized museums and dedicated galleries is that this history is cloistered away, rather than entwined through the narratives of every collection. It’s the Black History Month fallacy: the idea that all it takes to correct deeply entrenched bias and exclusion is four weeks of focus, rather than showing these stories and figures in their contexts, constantly. We see a handful of names and faces, but in the relentless focus on the history-book great individuals and their contributions, the picture is only ever incomplete.