More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

All that had to wait, though. First she needed to sieve the flour and the cornmeal. She found the box that held the sifter, a ring of tin with a mesh bottom, and brought out the flour sack. A few cupfuls at a time, she poured flour into the sifter and shook it over her largest cooking pot. The flour fell through the mesh, leaving behind an assortment of weevils, pantry moths, and flour worms. After she finished, she went outside to empty the sieve by flinging the insects into the yard. The sieved flour went into a big crock with a good tight lid. No pests could get into the crock; it would

...more

Images from her younger years appeared in her mind’s eye. Children taunting her, shouting derisively in fake Chinese, pulling at the corners of their eyes to mock her. The few who spoke to her did so only on a dare: When she answered, they would screech in triumph and run back to their friends. Their mothers were seldom better, and often worse. On spotting Hanna, they would cross the street hastily, sometimes covering their mouths as if she were diseased. Or they would pull their smaller children behind their skirts, protecting them. From what? Hanna always wondered.

“Finish,” Mama had said. “Good work is no good if you don’t finish.”

Hanna recalled the words of a popular folk song: Uncle Sam is rich enough to give us all a farm! Then she thought of the Indians she had met, and wondered, as she often had before, why Uncle Sam was allowed to give away land that wasn’t his in the first place.

Then Mama had seen what she was doing. Without a word, she took the wool away from Hanna. She brought out a hairbrush and a fine cord of red silk. After brushing Hanna’s shoulder-length hair, she plaited it carefully, weaving in the silk cord, then wrapping and tying it at the bottom of the braid. Standing behind Hanna at the mirror, Mama moved the braid to rest on Hanna’s shoulder. Hanna saw the red silk cord against her black hair, both of them smooth and shining. From that moment on, Hanna never again wished for blond curls.

If she were white, she wouldn’t be Mama’s daughter. And she wouldn’t have the same understanding of the precious knowledge that Mama had revealed to her a few weeks before she died. “I’m half-half too. Just like you.”

“You stop thinking about yourself. That’s where the sadness is, inside you. You look outside instead. At other people. You do things for other people, it fills you with good feelings, less room for the bad ones.”

Getting her into school had been a big enough hump; he didn’t need other reminders of the trouble that occurred because she was half-Chinese. He might well have heard that most families were keeping their children home from school, but he hadn’t said anything about it to her. Hanna rolled out the biscuit dough. A sudden pain seared through her, like a blow to her stomach.

She knew exactly what it was. It had happened before and would doubtless happen again. It was a piece of her heart breaking, from missing Mama. To Mama, the fact that Hanna was half-Chinese had been the most beautiful thing in the world.

“Sometimes beautiful things aren’t for buying. They’re for dreaming.” Hanna did not repeat that to Papa; he would have dismissed it as codswallop.

“That’s no excuse! What’s got into you, Hanna—since when did you care so much about the Indians?” It was a reasonable question. I always cared about the unfairness. But I used to think only of how white

people treated Chinese people. Now I know it’s about how white people treat anybody who isn’t white.

The design of a dress, she thought, could emphasize either the fabric or the cut. If the fabric was beautiful or special, the cut of the dress should be simple, to allow for long uninterrupted sweeps of the material. If the style of the dress was elaborate, then the fabric should be a plain weave in a solid color, the better to show off the structural details.

“She said no. Absolutely not. She said, ‘Mr. Edmunds, you know it’s against the law.’” Hanna’s mouth fell open in dismay. “Against the law?” “Yes. Illegal, for a white person to marry someone Chinese.” Hanna bit her lip, chilled by a nameless fear. She didn’t yet understand the depths of dread possible when unfairness was sanctioned by the law.

“Papa, I’m not. How could I be? If you and Mama hadn’t done what you did, I wouldn’t have been born. The both of you, and Miss Lorna, too—you knew that the law was wrong, and you did what you had to do.” “That was different.” “How?” “The law should stay out of a man’s personal business. As long as I wasn’t forcing your mama to marry me, it oughtn’t to be anyone’s business but hers and mine. And our families’.”

They were in favor of fairness and justice as long as it wasn’t too inconvenient or uncomfortable.

Mama had known the importance of helping other people—and of accepting help from them. The missionaries. Miss Lorna. Papa, their customers, her friends. Maybe that was part of what it meant to be independent: learning when to be strong on your own, and when to be strong with the help of others.

The ripple of hope was dissipating. It’s a hard thing, what I’m asking her to do. But somehow I have to get her to see that it’s not nearly as hard as being ignored and spited and attacked and hated, and losing

your business and your home . . . and the only real friend you’ve had in years.

But she realized now that she no longer needed the approval of the whole town. She had a home with Papa, work that she loved, and a few good friends.

Tea with friends is a feast for the spirit.

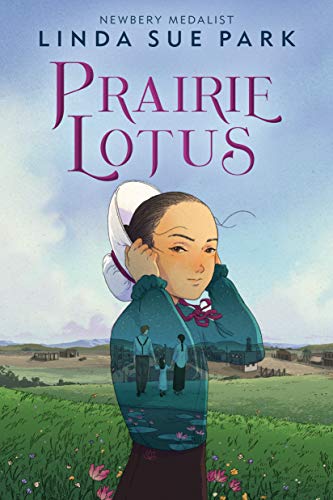

I WROTE HANNA’s STORY as an attempt at a painful reconciliation. Among the most beloved of my childhood books were those written by Laura Ingalls Wilder. I read them all many times—so often that to this day, fifty years later, I still know countless phrases and passages by heart.

we saw them as providing a kind of road map to becoming American.

As a child, I would lie in bed night after night,

imagining that I, too, lived in De Smet in the 1880s, and that I was Laura’s best friend.

There were, however, thousands of Chinese immigrants, most of them on the West Coast. They had arrived in two main waves: during the Gold Rush years of the 1840s and ’50s, and to help build the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s. Census records of 1875 show a population of Chinese in Deadwood, South Dakota, about 350 miles west of De Smet.

The stories I invented were a pre-internet version of fan fiction.

Her values of propriety and obedience over everything else seemed to me both misplaced and stifling. And Ma hated Native Americans.

I harbored a deeply personal sense of dismay over Ma’s attitude.

The racism that Hanna confronts is largely autobiographical: I have faced almost exactly the same incidents of racism depicted in the book.

Prairie Lotus is a story I have been writing nearly all my life. It is an attempt to reconcile my childhood love of the Little House books with my adult

knowledge of their painful shortcomings.

Dinah Stevenson pulled my first manuscript from the slush pile in 1997.

Ginger Knowlton has been my agent for more than twenty years, a relationship I cherish more than I can ever express.

My goal is to make new and different and better mistakes every day.