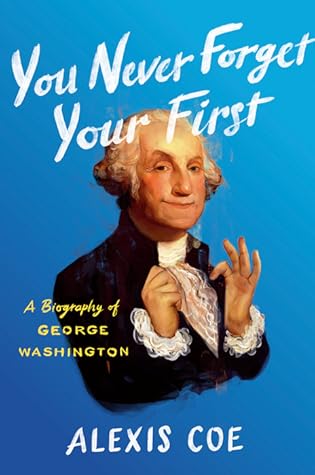

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alexis Coe

Read between

April 20 - May 4, 2020

The greatest threats to Washington’s life were armed men and deadly diseases.

No woman has written an adult biography of George Washington in more than forty years, and no woman historian has written one in far longer.

At the age of eleven, he inherited ten slaves from his father, and over the next fifty-six years, he would sometimes rely on them to supply replacement teeth. He paid his slaves for their teeth, but not at fair market value.

Everyone knows that, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, a woman is probably a shrew. And shrews, of course, need taming.

Great love stories don’t often begin with dysentery.

Although estates like Mount Vernon are called “plantations,” it’s a word inflected with genteel romanticism. If we look at what actually occurred there, we see them for what they were: forced-labor camps.

The figurehead of American liberty was never far from a representation of its (and his own) deep-seated hypocrisy.

America had always intended to succeed without a king, a dominant church, or a military leader, let alone an arthritic retiree with blurry vision, fogged hearing, a couple of teeth, and limited cash flow.

Adams argued that Washington be called “His Highness, the President of the United States of America, and Protector of the Rights of the Same.” When Jefferson got word in Paris, where he was serving as U.S. minister to France, of the spectacle, he wrote in code that it was “the most superlatively ridiculous thing I ever heard