More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

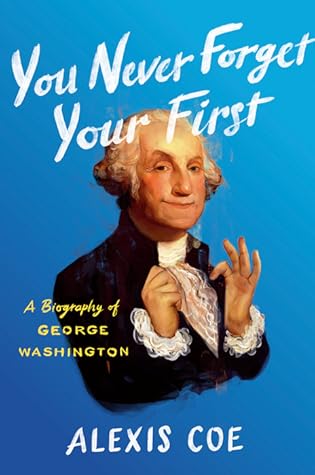

by

Alexis Coe

Read between

March 3 - March 18, 2020

If Washington had been a king, Americans waiting to celebrate him on the road to New York would have bowed, but since the country had evicted the monarchy, it was Washington who bowed to them. And they loved him for it. Hundreds of people walked alongside his small caravan to Baltimore, where he stayed the night. Well-wishers took him all the way to Wilmington, Delaware, the next day, and the day after that a military escort accompanied him to the Pennsylvania border. There the state president, Thomas Mifflin, escorted him, along with two cavalry units and a company of around a hundred men,

...more

After dinner at the governor’s mansion and a fireworks display, Washington, surely exhausted, settled into his new home at 3 Cherry Street, hoping to take advantage of the days before the inauguration. He was immediately thwarted. Everyone in New York seemed to know where he lived, and many showed up unannounced, looking for favors.

The best thing about the house was that Congress paid the yearly rent of $845. Washington argued, as he had during the war, that he should cover his own living expenses, which was great for optics but terrible for his pocketbook. Fortunately for him, the Constitution required compensation and Congress allotted him a twenty-five-thousand-dollar annual salary plus the cost of living. But the new government didn’t pay in advance, and like most Virginians, Washington was land rich and cash poor. In order to make it to New York, he had to secure a loan from Alexandria merchant Richard Conway.13

...more

“Long live George Washington, President of the United States!” Livingston shouted, prompting the crowds to erupt in cheers. A flag signaled an artillery salute, and Washington delivered his inaugural address. David Humphreys, a former aide-de-camp and an enthusiastic poet who inclined toward lengthy odes, had written a seventy-page draft back at Mount Vernon; Washington had opted to go with James Madison’s far shorter version, which clocked in at five hundred words. He spoke in general terms, promising to follow the Constitution and lead on behalf of the people.

Washington was pragmatic through it all; he had already outlived most of the men in his family, and he’d lived some of those years hard, which apparently showed. “Time has made havoc upon his face,” observed Fisher Ames, a congressman from Massachusetts, during the inauguration.18 It may have been a pained reaction to all the attention, but such comments would only become more frequent—and be made about every president who followed.

After the first session of Congress ended, Washington marked up his personal copy of the Constitution, writing “President” next to the sections that applied to him. He was extremely careful to satisfy every requirement of the office; a false move might kill the infant nation in its crib.5 What’s more, his decisions would shape how future presidents wielded power; he was determined that “precedents may be fixed on true principles.”6 The Constitution had been written by men he knew well, and could now call on to consult with, but it was ultimately up to interpretation. The first year of

...more

In Philadelphia, the Washingtons settled into a three-and-a-half-story brick mansion on Market Street. It had once served as British general Sir William Howe’s headquarters, and then as Benedict Arnold’s, just as he was being tempted toward treason; a financier named Robert Morris purchased it at the end of the war. Washington had been a guest there during the Constitutional Convention in 1787, and now he made it his own. The bathing room became the president’s office. Martha installed a new bed in their room and expanded others.

Washington would hold eight more meetings of the cabinet—a term coined by Madison—in 1791.19 “[I]n these discussions, Hamilton & myself were daily pitted in the cabinet like two cocks,” Jefferson later wrote.20 His description turns meetings into a blood sport, with Washington as the referee and Jefferson and Hamilton the razor-beaked competitors. By 1792, their fights spilled out of the cockpit. Jefferson and Madison, who were ideological allies, quietly funded Philip Freneau’s National Gazette, which criticized all of Washington’s policies and attacked Federalist supporters; he was, at least

...more

But he didn’t leave. Washington, then sixty, was once again named on the ballot of every presidential elector.31 He did not so much agree as capitulate to a second term, a decision Washington must have regretted on March 4, 1793, when he took his second oath of office against a backdrop of such immense international unrest, it threatened America’s very ability to survive.

With some effort, the troops arrested one hundred and fifty whiskey rebels. But without much evidence, and with few people willing to testify, only two men, John Mitchell and Philip Wiegel, were found guilty of treason. Although Washington bragged about the peaceful resolution, he must have felt embarrassed about the situation, or at least the reception his overreaction had received; he used a presidential pardon for the first time in history, and let the men go.

In the 1790s, Washington’s favorite breakfast was prepared by two enslaved house servants: Nathan, who slept in a bunk in the crowded greenhouse quarters, and Lucy, who lived in a nearby cabin with her husband, Frank Lee, a butler. Their days were long. They were expected to be in the plantation’s mansion house kitchen by 4:30 a.m. to prepare Washington’s breakfast. By 5 a.m., Lucy was stirring the hoecake batter she had prepared the night before, and by 6:30 a.m., she and Frank were frying the hoecakes and preparing coffee, tea, and hot chocolate. They may have added cold cuts or leftovers

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Washington was in good spirits until Lear, who had been reading the papers in the parlor, shared the latest on the Virginia Assembly. Monroe had been elected governor, with Madison’s backing, which left Washington “much affected.” He “spoke with some asperity on the subject,” Lear reported—probably a polite way to describe cursing. Take some medicine, Lear suggested on the way out. “You know I never take anything for a Cold,” Washington replied. “Let it go as it came.”

“We were governed by the best light we had,” Brown would later write to Craik. “We thought we were right; and so we were justified.”4 And by the medical standards of the day, and the information available to them, they were. But everything Craik, Brown, and Dick did made Washington’s condition worse. Around 4:30 p.m., Washington asked Lear to get Martha, who preferred to wait in another room. He sent her to his study to get the wills. (He had two: The earlier one, possibly dated around June 1775, had been drawn by a lawyer friend; the other was more recent.5) As he neared death, Washington was

...more

“I find I am going, my breath can not last long,” he said to Lear, their hands intertwined. “I beleived from the first that the disorder would prove fatal.” He asked that his longtime secretary see to his military letters and papers, his accounts and books, “as you know more about them than any one else.” Washington’s will gave Bushrod Washington, a favorite nephew and Supreme Court justice, control over his personal papers; after Martha died, he would inherit the mansion house, the surrounding farm, and much of the remaining estate.

“Doctor, I die hard,” Washington said when Craik appeared at his bedside around 5 p.m. “But I am not afraid to go.” He thanked the rest of the doctors for their “attentions,” but he would have no more. “Let me go quietly,” he said, as all but Craik retired. “I cannot last long.” They tried to make him comfortable, applying wheat bran to his legs and feet, then attempted another round of blistering. Eventually, though, all but Craik left “without a ray of hope.” Over the next few hours, Washington rarely complained, though he often asked for the time. The bloodletting had continued, and by that

...more

Perhaps it was a coincidence that he visited six months after Washington’s death, when he was running for president and would have benefitted from her support. Either way, she didn’t give it, and he won anyway. When she found out, a guest recalled that “she spoke of the election of Mr. Jefferson as one of the most detestable of mankind, as the greatest misfortune our country has ever experienced.”

There is ample evidence to suggest that Martha was disinclined to free Washington’s slaves before she had to, and may never have agreed to, or known about the plan to begin with. When she mentioned slaves in her letters, it was not uncommon for her to write things like “Blacks are so bad in thair nature that they have not the least Gratatude for the kindness that may be shewed to them.”9 In her own will, the slaves she controlled, whom she could have freed, she left to her family. It was not, then, morality that drove Martha to, on December 15, 1800, sign a deed of manumission, freeing all of

...more

In 1831, Bushrod’s nephew and heir, John Augustine Washington II, oversaw the completion of a new burial vault. The bodies of Washington, Martha, Bushrod, Fanny, and a few other family members were transferred to the exact verdant spot Washington had wanted, with small but significant deviations from what he’d envisioned. In 1837, his mahogany casket was enclosed in a marble sarcophagus bearing the Great Seal of the United States. During the Civil War, Confederate and Union soldiers carved their initials into the walls of the vault, a fitting addition to the resting place of the man whose

...more