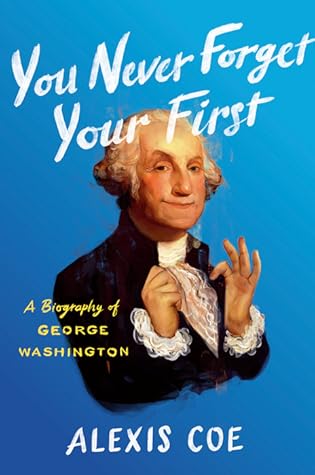

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alexis Coe

Read between

December 30, 2020 - January 4, 2021

No woman has written an adult biography of George Washington in more than forty years, and no woman historian has written one in far longer.

In fact, women historians have often reminded us that we don’t always know what we think we know.

Until the very end, Washington worries about respect and reputation. He needn’t have; the nation hasn’t always remembered him clearly, but we’ve never forgotten our first.

If the American Revolution had not taken place, Washington would probably be remembered today as the instigator of humanity’s first world war, one that lasted seven years.

He wasted no time riding out to her plantation, called White House.

It was the American colonists’ duty to resist such oppression on behalf of “mankind”—a category he understood to exclude mothers, sisters, wives,

and daughters, along with millions of slaves.3 It was an ironic choice of words considering Somerset v Stewart, a 1772 decision from the Court of the King’s Bench in London, which held that chattel slavery was neither supported in common law nor authorized by statute in England and Wales—a clear victory for abolitionists, which terrified Southern colonists.

Leutze managed to capture a certain against-all-odds spirit, which seemed to persuade the world that America was born righteous, so Washington along with it.

The figurehead of American liberty was never far from a representation of its (and his own) deep-seated hypocrisy.

Like pretty much all the delegates, he wanted to defer difficult decisions; he probably was in favor of allowing the slave trade to continue for another twenty years and counting slaves as three-fifths of a person for the allotment of representatives.

Washington argued, as he had during the war, that he should cover his own living expenses, which was great for optics but terrible for his pocketbook. Fortunately for him, the Constitution required compensation and Congress allotted him a twenty-five-thousand-dollar annual salary plus the cost of living. But the new government didn’t pay in advance, and like most Virginians, Washington was land rich and cash poor. In order to make it to New York, he had to secure a loan from Alexandria merchant Richard Conway.13

Washington was defining the role of president as he occupied it, and from the very beginning, it seems, he was sure about one thing: He wasn’t going to owe anyone any favors.

He was private about his religious views; he often spoke of “Providence,” rarely “God” and “Jesus” or “Christ.” He was most likely a deist, which meant he believed that God was responsible for the creation of the world, but does not intervene in it. Above all, he firmly believed in religious freedom; during his presidency, he would write as much to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island.

True to form, he rarely spoke in Christian terms; there was no mention of judgment, redemption, and while he mentions heaven, he leaves out a key Christian idea: a future reunion there.

Washington marked up his personal copy of the Constitution, writing “President” next to the sections that applied to him. He was extremely careful to satisfy every requirement of the office; a false move might kill the infant nation in its crib.5

What’s more, his decisions would shape how future presidents wielded power; he was determined that “precedents may be fixed on true principles.”6 The Constitution had been written by men he knew well, and could now call on to consult with, but it was ultimately up to interpretation.

Though Washington was sympathetic to the Federalists, he remains the only president who never claimed a political affiliation while in office.

Right after Washington refused to use military force against a foreign nation, he turned it on his own people in what would ultimately be the biggest overreaction of his life.

He became the first and only president to take up arms against his own citizens, and to come along for the ride—though he did so mostly from a carriage, dismounting only when it was time to review the troops.

The Constitution prescribed term limits of four years, but it did not restrict how many terms could be served; in choosing to stop at two, Washington set a precedent that would endure into the twentieth century, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt went for a third.

Political partisanship, Washington predicted, would reduce the government to a crowd of bickering representatives who were very good at thwarting each other but got very little accomplished for their constituents. And for all his talk of unity, he had come to see people as for or against his administration and had little patience for criticism. Unbridled partisanship was his greatest fear, and his greatest failure was that he became increasingly partisan.

The often repeated statement lacks crucial details and context: the slaves’ manumission was not immediate and other slave-owning founders, including Benjamin Franklin, didn’t emancipate their slaves in their wills because they had already done so while they were alive. After Franklin returned from France in 1785, he freed his slaves. In 1790, he petitioned Congress to abolish slavery—while Washington was president,