More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

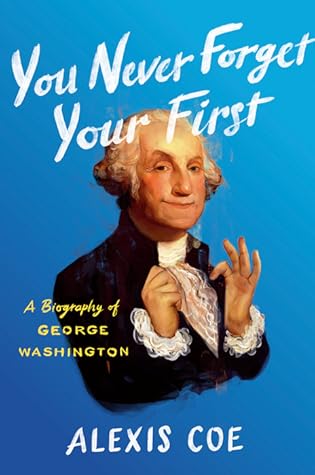

by

Alexis Coe

Read between

January 18 - January 28, 2021

In a young, monarchy-weary America, Washington’s lack of heirs gave him a distinct political advantage; it comforted people to know that he had no bloodline to preserve, no power-hungry scion to worry about.

In London, writer Samuel Johnson railed against the hypocrisy of “these demigods of independence” in a forty-page pamphlet asking, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?”

Washington’s insistence on being addressed by his title reminds us that he could be a brilliant tactician, but his strategic and intellectual victories off the battlefield have been totally overshadowed by his military triumphs during the Revolution. He won the war, but he didn’t do it with sheer force alone.

His ability to manage large-scale combat while also running spy rings and shadow and propaganda campaigns in enemy-occupied areas is a significant—and often overlooked—part of the Revolutionary War.

Washington rose to deliver his speech. His voice was surprisingly ragged and his hands were shaking, but the words he spoke were consistent with everything he’d said before: He was unworthy of the role of general, but aspired to the cause, and succeeded because of Divine Providence and the men who served under him.

“They wanted me to be another Washington.”13 But he couldn’t be. No one could.

What’s more, his decisions would shape how future presidents wielded power; he was determined that “precedents may be fixed on true principles.”

Political partisanship, Washington predicted, would reduce the government to a crowd of bickering representatives who were very good at thwarting each other but got very little accomplished for their constituents. And for all his talk of unity, he had come to see people as for or against his administration and had little patience for criticism. Unbridled partisanship was his greatest fear, and his greatest failure was that he became increasingly partisan.