More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

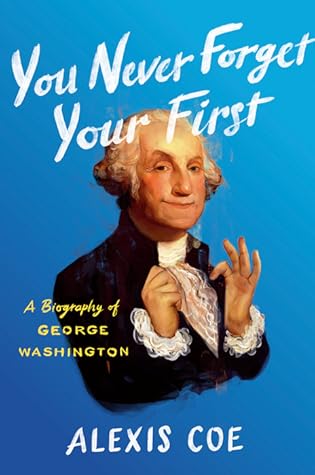

by

Alexis Coe

Read between

April 9 - April 12, 2020

In a young, monarchy-weary America, Washington’s lack of heirs gave him a distinct political advantage; it comforted people to know that he had no bloodline to preserve, no power-hungry scion to worry about.

Everyone knows that, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, a woman is probably a shrew. And shrews, of course, need taming.

America loves a self-made man, particularly one who overcomes the manipulations of a petty woman to seize his great destiny.

His Christian name might have been George Washington, but Tanacharison, known to Europeans as the “Half-King,” would call him “Conotocarious.” In English, it translated to Town Taker, or Devourer of Villages.

If the American Revolution had not taken place, Washington would probably be remembered today as the instigator of humanity’s first world war, one that lasted seven years.

Under the British imperial system, even the most enterprising colonist would remain second class. An Englishman who held a lower rank could order him around, and worse, that Englishman made more money than he did.

“My inclinations are strongly bent to arms,” Washington had written in 1754, when he was twenty-two, but he just couldn’t satisfy that desire in His Majesty’s forces. The next time he would join them on the battlefield, it would be to destroy them.

Parliament was using “despotism to fix the Shackles of Slavery upon us,” Washington said. It was the American colonists’ duty to resist such oppression on behalf of “mankind”—a category he understood to exclude mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters, along with millions of slaves.

In London, writer Samuel Johnson railed against the hypocrisy of “these demigods of independence” in a forty-page pamphlet asking, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?”

To pigeonhole him as a military leader is to underestimate how much the fledgling government needed Washington as a diplomat and political strategist. His ability to manage large-scale combat while also running spy rings and shadow and propaganda campaigns in enemy-occupied areas is a significant—and often overlooked—part of the Revolutionary War.

After the first session of Congress ended, Washington marked up his personal copy of the Constitution, writing “President” next to the sections that applied to him. He was extremely careful to satisfy every requirement of the office; a false move might kill the infant nation in its crib.

The first year of government was like the fourth trimester of a pregnancy; Washington had carried the baby to term, but now he had to figure out how to keep it happy, healthy, and growing.

Madison and Jefferson agreed to Hamilton’s financial plan. In exchange, the northerner agreed to a southern location for the permanent seat of government. Washington was pleased by the Compromise of 1790—in no small part because it moved the capital fifteen miles north of Mount Vernon. He signed the Residence Act in July (and the Funding Act a month later), creating a federal district around Georgetown in Maryland and Alexandria in Virginia, on his beloved Potomac.

Political partisanship, Washington predicted, would reduce the government to a crowd of bickering representatives who were very good at thwarting each other but got very little accomplished for their constituents. And for all his talk of unity, he had come to see people as for or against his administration and had little patience for criticism. Unbridled partisanship was his greatest fear, and his greatest failure was that he became increasingly partisan.

“The President is fortunate to get off just as the bubble is bursting, leaving others to hold the bag,” a resentful Jefferson complained to Madison. “He will have his usual good fortune of reaping credit from the good arts of others, and leaving to them that of his errors.”11

It’s hard to know how serious he had been over the years about liberating his slaves; when the topic came up in letters, he often said he would prefer to discuss it in person. Whether those discussions happened and how they went, we’ll never know. What’s clear is that, however Washington felt about owning human beings, he wasn’t willing to part with everything he had to free them.