More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

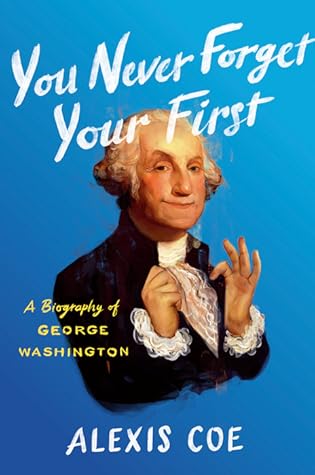

Alexis Coe

Read between

February 21 - February 24, 2021

there’s an expectation that women will write books about women; people of color will write about people of color. I was constantly reminded of this when I was asked what I was working on.4 The conversation often went like this: “What’s your book about?” “George Washington.” “His marriage?” “No.” “His wife?” “No.” “His . . . social life?” “No. It’s a biography. Like a man would write.”

A month earlier, he had ridden to Williamsburg and resigned his commission. He’d given up on the British military and, though he did not yet realize it, the British Empire. The French and Indian War set colonists, who had undergone their own cultural and social development in the New World, on the path to independence. They were learning that their goals and values differed from those of the crown, and that their concerns, even when voiced by the most ambitious, gifted, and loyal among them, fell on deaf ears.

Although estates like Mount Vernon are called “plantations,” it’s a word inflected with genteel romanticism. If we look at what actually occurred there, we see them for what they were: forced-labor camps.9

“[T]he once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched with Blood, or Inhabited by Slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous Man hesitate in his choice?” Washington had written from Mount Vernon, and in London, the British were asking the same thing.

Still, Paterson lingered, hoping for a message he could take back to the Howe brothers. Washington replied, smolderingly, “My particular compliments to both.”11 That swagger, from the leader of a far inferior, ill-trained army facing the greatest military power in the world, was all Washington. He’d lacked a cool head when he’d fought for the British, but in the seventeen years since he’d grown into a statesman.

If Washington had tried to match the Howe brothers in experience or armed forces, the war would not have been the second longest in American history.17 There likely wouldn’t be an American history. To pigeonhole him as a military leader is to underestimate how much the fledgling government needed Washington as a diplomat and political strategist. His ability to manage large-scale combat while also running spy rings and shadow and propaganda campaigns in enemy-occupied areas is a significant—and often overlooked—part of the Revolutionary War.

First, though, there was the small matter of his farewell address, which a congressional committee had been choreographing. There was no precedent, and no protocol. It was the first time in Western history that a general would be addressing his civilian superiors as he left military service.

The country celebrated his voluntary resignation, and in London, subjects of the British crown marveled over “a Conduct so novel, so inconceivable to People, who, far from giving up powers they possess, are willing to convulse to the Empire to acquire more.” King George himself allegedly said, upon hearing of the plan, “If [Washington] does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” America would spark an age of revolutions. When France experienced its own, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, he did not step down from power, but rather declared himself emperor. Years later, he would say, “They

...more

If Washington had been a king, Americans waiting to celebrate him on the road to New York would have bowed, but since the country had evicted the monarchy, it was Washington who bowed to them. And they loved him for it.

Washington was defining the role of president as he occupied it, and from the very beginning, it seems, he was sure about one thing: He wasn’t going to owe anyone any favors.

6 The Constitution had been written by men he knew well, and could now call on to consult with, but it was ultimately up to interpretation.

That's...bizarre. How was it left up to interpretation if he literally could ask the writers themselves? If that was the case, if Washington could ask Madison, "Hey, what did you mean by this?" and Madison just shrugged and said, "I dunno, it's up for interpretation!" then it's NO FUCKING WONDER we can't agree on what it means now.

To Washington, though, the damage was already done. At sixty-four, he wanted to retire, and this time, no one talked him out of it. The Constitution prescribed term limits of four years, but it did not restrict how many terms could be served; in choosing to stop at two, Washington set a precedent that would endure into the twentieth century, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt went for a third. Once again, he would shock the world by giving up power, overseeing a peaceful transfer from one systematically elected official to another.

10 Political partisanship, Washington predicted, would reduce the government to a crowd of bickering representatives who were very good at thwarting each other but got very little accomplished for their constituents. And for all his talk of unity, he had come to see people as for or against his administration and had little patience for criticism. Unbridled partisanship was his greatest fear, and his greatest failure was that he became increasingly partisan.

In lieu of coercion from the federal and state governments, Washington could have freed his slaves as an individual, but always found a reason or excuse not to. The main issue was always money. According to a Virginia law passed in 1782, he could set any number of enslaved men, women, and children above forty-five years or under twenty-one (for men) and eighteen (for women) free if they could be “supported and maintained by the person so liberating them.” If he failed to do so, the court would “sell so much of the person’s estate as shall be sufficient for that purpose.”19

It’s hard to know how serious he had been over the years about liberating his slaves; when the topic came up in letters, he often said he would prefer to discuss it in person. Whether those discussions happened and how they went, we’ll never know. What’s clear is that, however Washington felt about owning human beings, he wasn’t willing to part with everything he had to free them.

In 1837, his mahogany casket was enclosed in a marble sarcophagus bearing the Great Seal of the United States. During the Civil War, Confederate and Union soldiers carved their initials into the walls of the vault, a fitting addition to the resting place of the man whose fondest hope was for the nation to be unified. Both sides, the South and the North, the slave-owning and the free, viewed him as their inspiration. And both were right.