More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

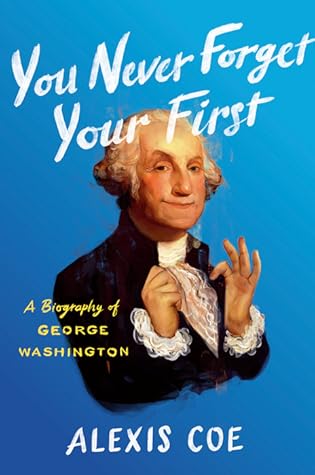

Alexis Coe

Read between

June 20 - June 23, 2022

Like many land-rich, cash-poor Virginia planters, including Thomas Jefferson, Washington got behind on his payments to London purveyors, and was soon in debt.

It was an ironic choice of words considering Somerset v Stewart, a 1772 decision from the Court of the King’s Bench in London, which held that chattel slavery was neither supported in common law nor authorized by statute in England and Wales—a clear victory for abolitionists, which terrified Southern colonists.

Votes were taken. In Philadelphia, miraculously, the delegates reached a unanimous decision on June 15, 1775: They would raise an army, and George Washington would lead it. Parliament took a vote, too, later that summer, but they were not united. Only 78 members voted for conciliation; 270 nobles and lords were eager to teach the rebellious colonists a brutal lesson.

As one of his favorite writers, Joseph Addison, wrote in a play called Cato, “Thy life is not thy own, when Rome demands it.”

a deal. Madison and Jefferson agreed to Hamilton’s financial plan. In exchange, the northerner agreed to a southern location for the permanent seat of government. Washington was pleased by the Compromise of 1790—in no small part because it moved the capital fifteen miles

Rather, democratically elected officials had voted it into law. He saw these local attacks as a direct challenge to legitimate federal

authority and was determined to quash the protest and have its participants tried for treason.

Washington saw a rebellion, but Mifflin saw isolated (and largely whiskey-fueled) acts of desperation from a community that felt unheard. Only land-owning white men could vote, and land ownership in western Pennsylvania

had fallen dramatically since the earliest period of white settlement. In some townships, none of the locals owned any land at all; their landlords—the ones who were allowed to vote—lived in the big cities. Much of the population covered rent and other necessities by bartering crops or whiskey. They rarely paid in cash, which was scarce in the region. For the majority of the population, then, even a low yearly tax would leave them with nothing.

“Whenever the government appears in arms, it ought to appear like a Hercules,” Hamilton would write in 1799, and the twelve thousand soldiers he led toward what is now Pittsburgh showed he meant it.13

The following year, thirteen tribes ceded more than twenty-five thousand acres of land to the federal government, in exchange for $25,000 down and an annual payment of $9,500.

The press was stunned by Washington’s imprudence: The man famous for his self-control and judiciousness had neglected to consider whether military action was warranted. Couldn’t he have simply threatened the poor civilians into submission—or, better yet, actually talked to them?

During his sixth annual address to Congress, he blamed “Self created Societies” for inflaming dissent against the government and causing greater divisions across the country.

In a letter to James Monroe, then US minister to France, Madison wrote that the “introduction of [Self created Societies] by the President was perhaps the greatest error of his political life.”

Hoping to avoid another war with the British, Washington sent John Jay, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, to London to negotiate a treaty. Given the slow pace of transatlantic mail, the administration would be unable to weigh in on negotiations in real time, so Jay traveled with a set of notes.

But they didn’t come from his current cabinet. They came from Hamilton; he was now practicing law privately in New York,

Hamilton couldn’t just leave it to Jay, the actual negotiator, to handle discussions on his own. So he back-channeled with British leaders, assuring them America would not, as Denmark and

Sweden had, defend its neutral stance with arms. The Brits’ concern over direct engagement was the only card Jay had to play, and Hamilton showed them his hand.

When anti-administration newspapers printed the treaty in full, people hurled stones at Hamilton on the street, burned effigies of Jay, and sent Washington an overwhelming

amount of hate mail. “Tenor indecent—no answer returned,” he wrote on one.22

the Republicans in the House, led by Madison, refused to let the Jay Treaty go, and a standoff ensued. In the spring of 1796, they demanded that the president share the diplomatic

instructions Jay had received. Washington refused, asserting for the first time what would become known as executive privilege.

The Republicans threatened to withhold the funds necessary to put the treaty into effect. Washington called that unconstitutional, arguing that the Senate and the president made tre...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

He won on all fronts. Hamilton’s notes stayed private, and the treaty was a success; trade expanded, and, once the British evacuated their northw...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

And with that, Washington was no longer interested in inviting another Democratic-Republican into his cabinet, his confidence, or anywhere else. “I shall not, whilst I have the honor to administer the government, bring a man into any office of consequence knowingly, whose political tenets are adverse to the measures, which the general government are pursuing,” he wrote to Timothy Pickering on September 27, 1795. “For this, in my opinion, would be a sort of political Suicide.”28

praised the infant country’s rapid progress, which would continue if it focused on ambitions, not alliances; “the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.” Foreign influence was the enemy of American unity and prosperity, he wrote, because it whipped up “jealousy, ill-will, and a disposition to retaliate.”

He worried that “cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people, and to usurp for themselves the reins of Government.”10 Political partisanship, Washington predicted, would reduce the government to a crowd of bickering representatives who were very good at thwarting each other but got very little

accomplished for their constituents. And for all his talk of unity, he had come to see people as for or against his administration and had little patience for criticism. Unbridled partisanship was his greatest fear, and hi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The election did nothing to bridge the partisan divide during Washington’s final winter in Philadelphia. After

Andrew Jackson, serving his first term in the House of Representatives from the newly inducted state of Tennessee, refused to salute or applaud Washington.

That same day, February 22, 1797, Hercules, originally considered the greatest flight risk among the president’s slaves, ran away—but not from Philadelphia. He had been sent back to Mount Vernon after his son, Richmond (whom Washington begrudgingly brought to the city to make Hercules happy), had been accused of stealing

from a guest the previous year.12 Washington assumed the alleged robbery was a part of a plan to escape, and sent Hercules back to Mount Vernon—but not to the kitchen. Hercules spent the rest of 1796 and early 1797 crushing gravel, digging ditches, and doing whatever backbreaking work was assigned to him, under an overseer’s watchful eye, and whip. This suggests he was telling the truth when he pledged fidelity to Lear six years earlier, and it was the punishment he received that prompted him to flee, leaving behind his three children.

He never got close to finding Hercules, but shortly after Adams was elected in November, Judge was spotted in New Hampshire, where slavery was abolished in 1783. Washington sent Whipple to compel her to return to Virginia.

Judge actually agreed, but not without terms: She would remain with the Washingtons until they died; the end of their life would signal an end to her bondage. And she would not be gifted or sold to anyone. When Whipple wrote as much, Washington went apoplectic.

he had sold his slaves on at least three occasions, and he did so knowing that the place he was sending them, the West Indies, would

bring about a brutal change in their lives. They would likely work on sugar plantations under overseers who were quick to use their whips; their diets would be poor, their medical care worse. They were virtually guaranteed a premature death.

Yet, since the Revolution, he had been saying that he wished “to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptable degrees.”

Washington always emphasized that emancipation be gradual; one could argue that this was to acclimate everyone to the notion, but it would, most importantly, lessen the financial blow to slave owners. Still, he did nothing to address the issue while he was in office.

In his will he stipulated that his hundred and twenty-three slaves should be freed—after Martha had her use of them, and the income they would generate.

Upon the decease of my wife, it is my Will & desire that all the Slaves which I hold in my own right, shall receive their freedom. To

And to my Mulatto man William (calling himself William Lee) I give immediate freedom;

Washington had always seen Lee as exceptional. He did not free him sooner, though, because he truly believed, as he often said, that Lee was better off in his “care.”

When she found out, a guest recalled that “she spoke of the election of Mr. Jefferson as one of the most detestable of mankind, as the greatest misfortune our country has ever experienced.”4

Washington’s will had been circulated in pamphlet form. Some of his slaves had decided to immediately emancipate themselves and fled Mount Vernon, while the rest watched her closely, knowing that her death meant their freedom.

There is ample evidence to suggest that Martha was disinclined to free Washington’s slaves before she had to, and may never have agreed to, or known about the plan to begin with.

In her own will, the slaves she controlled, whom she could have freed, she left to her family.

It was not, then, morality that drove Martha to, on December 15, 1800, sign a deed of manumission, freeing all of her late husband’s slaves. It was self-preservation.

When Martha died a little over a year later, on May 22, 1802, at the age of seventy, the hundred and fifty dower slaves who remained at Mount Vernon were divided among her four grandchildren. About twenty families were separated; many would never see each other again.