More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Maybe it’s just that we’re all made of stardust.

I experienced at these times a kind of clarity and intensity of emotion that I had never known before: fear, anxiety, calm, loneliness, utter dread, love, an otherworldly focus. In the vortex of cancer, all other sounds drown out, and you hear only the beating of your heart, the drawing of your own breath, the uncertainty of your footfalls. You may be surrounded by the hugest crowd of family and friends, and by the shiniest love, but you walk alone through these medical valleys of darkness.

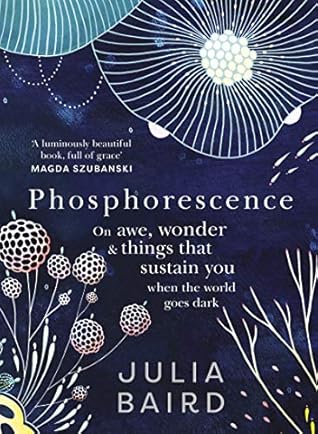

What has fascinated and sustained me over these last few years has been the notion that we have the ability to find, nurture and carry our own inner, living light — a light to ward off the darkness. This is not about burning brightly, but yielding simple phosphorescence — being luminous at temperatures below incandescence, quietly glowing without combusting. Staying alive, remaining upright, even when lashed by doubt.

First, pay attention. Second, do not underestimate the soothing power of the ordinary. Third, seek awe, and nature, daily. Fourth . . . well, so many things: show kindness; practise grace; eschew vanity; be bold; embrace friends, family, faith and doubt, imperfection and mess; and live deliberately.

In Australia, the dawn is an arsonist who pours petrol along the horizon, throws a match on it and watches it burn.

He reminds us that ‘the mind evolved in the sea. All the early stages took place in water: the origin of life; the birth of animals, the evolution of nervous systems and brains, and the appearance of the complex bodies that makes brains worth having . . . When animals did crawl onto dry land, they took the sea with them. All the basic activities of life occur in water-filled cells bounded by membranes, tiny containers whose insides are remnants of the sea.’ In other words, the sea is inside us.

Studies have shown that awe can make us more patient and less irritable, more humble, more curious and creative — even when just watching nature documentaries. It can ventilate and expand our concept of time:

THERE ARE SEVERAL SACRED aspects to how Australians submit to the sea. First is the way we are drawn to it, gazing out at its expanses, and lie down near it whenever we can. Second is the purifying ritual of plunging, and third is immersing in it and exploring its subterranean secrets. A fourth may be the surfer’s learned respect for its thunderous swells, tides and curling waves.

We spend a lot of time in life trying to make ourselves feel bigger — to project ourselves, occupy space, command attention, demand respect — so much so that we seem to have forgotten how comforting it can be to feel small and experience the awe that comes from being silenced by something greater than ourselves, something unfathomable, unconquerable and mysterious.

In short: when we are exposed to sunlight, trees, water or even just a view of green leaves, we become happier, healthier and stronger.

Yet no one really knows why it works. It could be the peace, the distraction, the fact our brains can unfurl, the birdsong, or even chemicals (phytoncides) exuded by trees, as Dr Li believes. Think of the terms used by nature scientists to describe the way humans act in forests. Effortless attention. Soft fascination. Absorption.

Everywhere, curious souls are closing their eyes in woods, listening to birdsong and rustling leaves, smelling moss, oaks, eucalypts, ferns, flowers in bloom, and breathing deep, hoping to find something they feel they have lost — or at the very least, sense it nearby.

Country is loved, needed and cared for, and country loves, needs and cares for her peoples in turn. Country is family, culture, identity. Country is self.’

The greatest obsolete word, which I am eager to bring back into usage, is apricity, meaning ‘the warmth of the winter sun’. When you’ve plunged into icy seas and returned to shore with stiff red fingers and numb toes, there can be few delights as sweet as sitting in the sun’s light, soaking up the apricity, thawing down to the bone.

‘after a few hours of dejected driving, the night sky would darken, clear itself of clouds, and a million sparking diamonds would appear’. He would then pull over on the side of the road, stop his car, ‘turn off the lights, look up — and begin healing, amidst wonders that make my small pain even smaller — until it disappears altogether. How can anything you say, or do, or feel matter beneath such stunning beauty and depth? This is also storm chasing.’

SILENCE IS NOT JUST the absence of noise, or even unnecessary noise. It is the absence of noise made by human beings. It is rare, and shrinking.

Now Hempton’s passion is the preservation of true natural silence, which he describes not as the ‘absence of something, but the presence of everything.’ It is many sounds, he says: Silence is the moonlit song of the coyote signing the air, and the answer of its mate. It is the falling whisper of snow that will later melt with an astonishing reggae rhythm so crisp that you will want to dance to it. It is the sound of pollinating winged insects vibrating soft tunes as they defensively dart in and out of the pine boughs to temporarily escape the breeze, a mix of insect hum and pine sigh that will

...more

Are we even capable of being still without our hands darting for our phones? Yet if generations of mystics and seekers have insisted that something connects silence with the sublime, you have to wonder who we could be if we paused more often.

sometimes, in order to learn, you need to slow down, shut up and allow yourself to sit in silence.

We learnt by watching and listening, waiting and then acting . . . There is no need to reflect too much and to do a lot of thinking. It is just being aware.

We watch the moon in each of its phases. We wait for the rain to fill our rivers and water the thirsty earth . . . When twilight comes, we prepare for the night. At dawn we rise with the sun. We don’t like to hurry. There is nothing more important than what we are attending to. There is nothing more urgent that we must hurry away for.

In greeting each morning, remind yourself of dadirri by blessing yourself with the following: Let tiny drops of stillness fall gently through my day.’

When you shrink, your ability to see somehow sharpens. When you see the beauty, vastness and fragility of nature, you want to preserve it. You see what we share, and how we connect. You understand being small.

And he pointed out that recognising that all of humanity’s creation, and millennia of delight and pain, of hubris and striving, have all taken place on this tiny, distant speck must surely help us realise the importance of being decent and careful with each other, and of protecting and loving the Earth.

These findings are important because they show that the effects of kindness can flow on for decades, so that generative acts inspire others to act the same way, and ‘create a virtuous cycle of care, generation after generation’.

They bothered me; but I could not throw them out. I could not entirely figure out why. I think I wanted to think that the tale they told mattered.

Why do we keep these fragments, why do we honour these moments of our younger selves? Is it the memory of hope? Is it the belief that even this history, piecemeal and peripheral, matters? What makes a story worth remembering?

And it’s about allowing ourselves to try, and honouring ourselves for caring, trying and giving a damn.

Somehow this culture shaped me, then spat me out.

The lesson is: you don’t walk away until the work is done.

Such efforts — when people work for justice or simply to improve the lives of other people, and try to ensure the voiceless are heard and the marginalised are pulled into the centre, but get nowhere, for a very long time — are not failure but examples of striving without instant reward. And there is a dignity to this.

Why do we even preserve archives — the stuffed boxes in our attics that tell our own stories, as well as those in distinguished libraries that preserve the documents of influential figures? And where is the line between hoarding and preservation? What it is crucial to understand is that to keep records is to insist on significance: by doing so, you place something on record, and assert that it is of note. You are saying that it is something people should remember, that they may want to find out about at some point. If it is marked down, they will be able to do that. Women have not historically

...more

Archives, then, are not passive storehouses of old stuff, but active sites where social power is negotiated, contested, confirmed.

Historically, archives have excluded the stories of women, of people of colour, of the LGBTQI communities, of those inhabiting peripheries. The records of their lives have been discarded or lost, while those of small groups of powerful men have been carefully polished, even the smallest fragments collected and kept. Now the rest of us need to insist our stories matter.

So if you have leaned your weight against something disturbing or unjust and it apparently remained unchanged, remember this: weight is cumulative.

The truth is that progress has always been defined, fuelled and foiled by mess and mistakes as well as might. When you think of your own bursts of activism, or volunteering, or your efforts to just change something you cared about, honour the fact that you tried, whether it was to do with human rights, pipelines, corruption, water, fraud or freedom.

idea about tossing out all objects that don’t give us joy makes a crucial omission: that objects have intrinsic value as triggers of memory and nostalgia, and therefore help us document our lives? And if that’s true, which morsels matter, how do we curate the objects in our lives?

Yet why does any of this even matter to us? Perhaps we should stop snapping and gathering, framing and filtering and posting, and learn to accept that there is beauty and depth in temporariness.

The cherry blossom’s glory is also annual, and its shedding is glorious: petals swirl in eddies in the air, sometimes spiralling to the tops of office buildings — I used to watch the tiny white shapes dance in the wind outside my New York office, high up on the seventeenth floor on West 57th Street.

Perhaps US author Anne Lamott is right when she says, ‘Hope and peace have to include acceptance of a certain impermanence to everything, of the certain obliteration of all we love, beauty and light and huge marred love.’ Some things — and faces — are better left alone. Some things are best left ephemeral.

The universal law, then, is that impermanence governs all things.

A finite lifespan, he tells me, is what makes street art singular: it blooms suddenly, then is exposed to the elements.

It’s a fragility meant to heighten appreciation. Rone told me recently, ‘If you are lucky enough to come across a piece of work you like, you know it may not be there next time you visit, so you have to appreciate in that moment.’

But if we are conscious of the temporariness of anything, or everything, we will be far less likely to squander time looking backwards, or forwards, to other moments than the one we are in. If we accept flowering is by its nature a fleeting occurrence, then we are more likely to recognise each bud as a victory, each blossom as a triumph. And if we accept impermanence, we are far more likely to live in the present, to relish the beauty in front of us, and the almost infinite possibilities contained in every hour, or a single breath.

It’s as though women must both be perfect and mask any striving to that perfection — any sign of straining, or of work, incites contempt.

A CONSEQUENCE OF UNIFORMITY for women — and, increasingly, men — is erasure of character. It seems trite, or retro, to remind ourselves that beauty is warmth, conversation, intelligence and a certain grace or magnetism, too, but it’s true.

How rarely we applaud the sheen of antiquity, the patina of a life lived.

Mum has taught me so many crucial lessons. First, that grace — showing generosity and forgiveness even to those who do not deserve it — is not weak but extraordinarily powerful. Second, that kindness should not just be an aspiration but a daily practice, a muscle that, if exercised, can grow strong and become a habit or a way of life. Third, that sometimes you do not need to overthink resilience.

It can take a while, sometimes, to be the woman you want to be, and to excavate the misogyny or critical eye we too often internalise.

First, demand respect, and give it. Sometimes, when you do this, you will feel insane, or be told that you are. Persist. Use your brain. You will doubtless be praised for your sunny face, your kind ways and your grace, but you must also always use, protect and stretch your fine brain. Women threw themselves under horses, starved, marched and fought for you to be able to speak and be honoured.