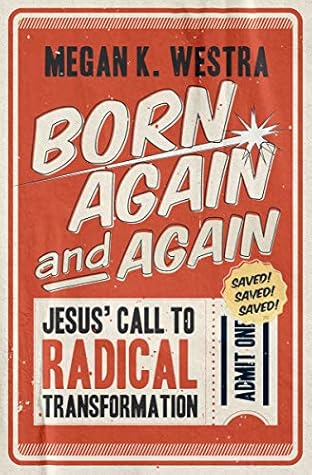

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Megan Westra

Read between

February 3 - February 7, 2022

But the Jesus I invited them to ask into their hearts had nothing to say about the daily struggles of their families and communities. This Jesus had nothing to say about why all the businesses had fled from their neighborhood, or why Jesus cared about their souls but not about whether they had anything to eat that morning.

The cover of the booklet announced, “Good news!” but the first page condemned the reader as a hopelessly depraved, hell-bound sinner. Not to worry, though—if the reader persevered, there was a prayer on the final page that would magically undo their depraved sinner status and secure their eternal reward in heaven with God.

Justice wasn’t a helpful and hip addition to the gospel; it was intrinsic to the gospel. I got saved again, although I wouldn’t know it until years later.

I’m learning that the faith I love so much, that has raised me and held me tenderly, has been a crushing fist of oppression in the lives of others. I’m learning that the community of people who have given me a sense of identity for my whole life, and who encouraged me to place Christ first, have largely traded following a poor carpenter turned itinerant rabbi for pursuit of mansions in the sky. Increasingly, I am aware that the God about whom the Scripture bears witness has little to do with the god promoted in those little blue books I handed out long ago.

As Moana’s grandmother teaches us in the 2016 Disney film, “the people you love will change you.” When Christ commands us to love our neighbors and our enemies, this means we’re destined for lots of change. Let’s shift the story together.

The congregational landscape today is often characterized by the inverse: consumption over connection. Many American churches reflect a belief that the church exists primarily to meet the needs of members, rather than seeing itself as a community where lives are transformed through relationships.

This super-personal, highly privatized way of understanding what it means to be saved doesn’t have much historical precedent, though. Conversionism, as we know it today, was an unthinkable theological position not so long ago.

It is not that understanding salvation as personal is wrong, but an overemphasis on Jesus as personal Lord and Savior leaves us with an understanding of salvation that is incomplete, distorting both our view of the world and the practice of faith.

The rise of itinerant preachers in early America launched the Reformation value of individual interpretation of Scripture into hyperdrive, removing the reading and interpretation of Scripture from a community context and entrusting one authoritative figure who transcended all institutions to receive the word of the Lord.

It is a faith that allowed colonizers to rebel against a monarchy for being exploitative while at the same time enslaving their neighbors or stealing their neighbor’s land. It is a faith that allowed evangelicals in the 1930s to feel concern for their starving neighbors during the Great Depression yet vote against policies that would help provide access to food.

What would happen if our faith communities and church congregations adopted the same practice of pausing to listen to how our actions affect—intentionally or not—those whose lives are devalued by society at large? Those whose racial, sexual, or gender identity has barred them from the doors of so many congregations?

Just when we think we’ve pegged down the type of folks Jesus loves most, he turns around to accept the invitation of someone who is exactly the opposite. Because that’s who Jesus loves the most—the person you can’t stand, and also you.

God certainly is concerned with our particularity, and the ways in which we encounter the initial call of salvation vary.

There is a personal aspect to salvation, but this becomes restrictive and reductive when we insist on experiencing salvation only in the particularities of our personhood.

The question is not, “Will our theology be contextual?” but, “Will we be aware enough of our context to account for it as we do theology?” Presenting theology without being aware of, or while being dishonest about, how our context and experience inform our theology is a hallmark of a consumeristic framework.

An exclusively personal view of salvation creates an understanding of salvation that depends completely on the spiritual performance of each individual in isolation.

An overly personalized view of salvation also creates an understanding of salvation that lacks the strength to address systemic suffering.

If my relationship with Jesus is merely a label for a deeply felt, but purely private, religious faith,6 then I can spend my whole life investing in building a kingdom without ever considering if I’m supporting the kingdom of God or an empire of this world.

Primarily, the call of salvation is a declaration of belonging.

“Restricting God to private space was the great heresy of the twentieth-century evangelicalism. Denying the public God is a denial of biblical faith itself, a rejection of the prophets, the apostles, and Jesus himself.”

“The nation cannot profess Christianity, which makes the golden rule its foundation stone, and continue to deny equal opportunity for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness to the black race.”

Artist and activist Bree Newsome Bass, the woman who climbed the flagpole of the statehouse in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015 to tear down the Confederate flag, did so while reciting the Lord’s Prayer and Psalm 27.

But prayer and prophetic critique are not mutually exclusive, and when we insist that they are, we diminish the scope and impact of our prayer.

While there is merit to this belief, choosing to abstain from voting is a choice afforded mainly to those whose privilege within the system insulates them from being negatively affected by changes in policy.

That’s what I imagine discipleship looks like—showing up for the people in our world who are in pain, putting our bodies on the line, literally, for the sake of the flourishing of the image of God in others. It sounds like what Jesus did.

The German theologian Karl Barth is credited with advising people to read the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other.

eliminating the rights of European women, relegating all people of African descent to three-fifths humanity, and completely denying the humanity of Indigenous people, the Constitution theologically functions to bolster the belief that European men are more godlike than anyone else.

The slave apologists of the era dug in to defend their direct, literal readings of Scripture, and to support the theology of a divinely inspired hierarchy.

His rhetoric played easily to the revivalism of the moment, and echoed the popular idea of the pure, spiritual Christianity that featured a personal Jesus who would come live a quiet, private life in the hearts of true believers.

Instead they clung fearfully to the idea that the world must be coming to an end. In reality, these white evangelicals were facing down the dead end of their own stunted imaginations.

The authors of the Bible were largely, though not exclusively, living at the margins of their societies, not in positions of power, and they wrote for people who also were largely on the margins.

They are advocating for taking the risk of loving and caring for someone who has exploited them and their people. For modern readers approaching the Bible from social positions valued and empowered by society at large—white, male, educated, currently able-bodied, wealthy or middle class—we have internal work to do as readers before we will be able to read the text with integrity.

There is abundant evidence across the canon that the movement of those seeking after God is toward those who are considered outsiders and who have been devalued by society.

To flatten our faith to a singular voice and story is insulting to the complex tapestry of God’s creation. God is not a white man. God is beyond.

Because I know where true power lives, I can demand that the authorities in my day—in my city and my country—wield their power for the defeat of racism, militarism, poverty, and arrogance.

Even though all my required seminary classes taught me the theology of white men, I had to learn that the Spirit of God permeates all cultures and reveals God’s truth through the dark-skinned grandmother who passed down her faith to me, although she had little education.

Will I choose to see God not as a white man on a throne, but as the fierce and dedicated Latina mother who crosses all borders in hopes of her children flourishing?

Whiteness convinces people that the world should orient around fulfilling their individual desires and eliminating their personal pain or discomfort.

the errors of the church in relationship to race have been largely systemic, and as such must be addressed not only on a personal level but on a corporate level as well.

Public sin requires public correction

The vision of justice provided by Scripture is always restorative and transformative.

The thing about a plain, self-evident reading of the text, though, is that any piece of Scripture can easily be ripped from the greater context and manipulated to support whatever ends the reader is seeking to advance.

He maintained a firm stance on the gospel being an inherently spiritual matter, deeply felt, and personal, rather than the gospel taking on flesh and moving into the neighborhood.

To attend faithfully to the context of Scripture, we must also consider passages about land, crops, and harvests, something that people living in agrarian economies would have known instinctively.

In short, the approach to debt in the Hebrew Scriptures was to require only the payment—not interest—and to do so in a way that did not inhibit the indebted person’s livelihood to a significant degree. Maintaining human dignity was at the center of the ethic on debt.

Sabbath, in emphasizing the nature of life as antithetical to commodification, undermines any notion of tallying up salvation totals, or measuring success by the number of congregants in attendance.

This ethic also assumes that for those who are wealthy, there is an obligation to care for those who have fallen on hard times.

Just as land and harvest were deeply associated with the financial system of the day when the Bible was being written, what are the resources associated with our financial system today?

The practice of tithing reminds us on a personal level that the resources and money we use are a gift. We do not own them.

Industry tactics aimed at taking possession of wealth at the expense of human dignity and flourishing are morally wrong. Christians have a responsibility to speak truth to the system (even if the system does not change!) and to say that this is not the way things should be.