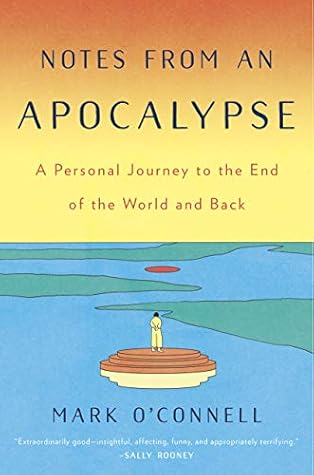

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 19 - April 26, 2020

We are alive in a time of worst-case scenarios. The world we have inherited seems exhausted, destined for an absolute and final unraveling. Look: there are fascists in the streets, and in the palaces. Look: the weather has gone uncanny, volatile, malevolent. The wealth and power of nominal democracies is increasingly concentrated in the hands of smaller and more heedless minorities, while life becomes more precarious for ever larger numbers of people. The old alliances, the postwar dispensations, are lately subject to a dire subsidence. The elaborate stage settings of global politics, the

...more

Should we just ignore the end of the world?

Our end of the world, on the other hand, is sung from the rooftops even by the sparrows; the element of surprise is missing; it seems only to be a question of time. The doom we picture for ourselves is insidious and torturingly slow in its approach, the apocalypse in slow motion.”

Writing in the fifth century AD, Saint Augustine observed that three centuries before his own time, the earliest followers of Jesus, consumed with apocalyptic fervor, believed themselves to be living in the “last days” of creation. “And if there were ‘last days’ then,” he wrote, “how much more so now!” The point being, for our purposes here, that it has always been the end of the world.

The idea of collapse speaks, on some primal level, to a reactionary sensibility—a sensibility in which the world is always necessarily in an advanced state of degeneration, having fallen from a prelapsarian wholeness and integrity.

Everyone was always saying these days that it was easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Everyone was always saying it, in my view, because it was obviously true. The perception, paranoid or otherwise, that billionaires were preparing for a coming collapse seemed a literal manifestation of this axiom. Those who were saved, in the end, would be those who could afford the premium of salvation.

If it’s not an outright work of postapocalyptic nonfiction, then The Lorax is about as close to being one as an illustrated book for preschoolers has any business being.

“those who expected signs and archangels’ trumps / Do not believe it is happening now.”

“There will be no other end of the world, / There will be no other end of the world.”

In the Old Testament, some of God’s more memorable threats to various insubordinates, various enemies of his people, involve ruined cities as the terrain of roosting birds. In the Book of Jeremiah, He declares that the city of Hazor, in the wake of its destruction by Babylon, will become “a haunt for jackals, a desolation forever.” And then there is the great blood-fevered edict of Isaiah 34, where it is foretold that the Lord’s righteous sword will descend on the city of Edom—her streams turned into pitch, her dust to blazing sulfur, her land lying desolate from generation to generation—and

...more

Just as I want him to continue believing in Santa Claus for as long as possible, I want to defer the knowledge that he has been born into a dying world. I want to ward it off like a malediction.

The future is a source of fear not because we know what will happen, and that it will be terrible, but because we know so little, and have so little control. The apocalyptic sensibility, the apocalyptic style, is seductive because it offers a way out of this situation: it vaults us over the epistemological chasm of the future, clear into a final destination, the end of all things. Out of the murk of time emerges the clear shape of a vision, a revelation, and you can see at last where the whole mess is headed. All of it—history, politics, struggle, life—is near to an end, and the relief is

...more