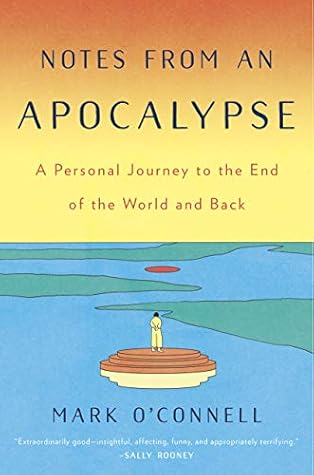

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 20 - April 28, 2020

We are alive in a time of worst-case scenarios. The world we have inherited seems exhausted, destined for an absolute and final unraveling.

Our end of the world, on the other hand, is sung from the rooftops even by the sparrows; the element of surprise is missing; it seems only to be a question of time. The doom we picture for ourselves is insidious and torturingly slow in its approach, the apocalypse in slow motion.”

There is no one cause, no single locus of apocalyptic unease. It’s all horsemen, all the time.

Because I wanted to look it in the face, this future-dread, to see what might be learned from it, what might be gained for life in the present.

This book is about the idea of the apocalypse, but it is also about the reality of anxiety. In this sense, everything in these pages exists as a metaphor for a psychological state. Everything reflects an intimate crisis and an effort at resolving it. I

Prepping is rooted in the apprehension of an all-consuming decadence. Society has become weak, excessively reliant on systems of distribution and control whose very vastness and complexity renders them hopelessly vulnerable.

The failure to acknowledge, or even to perceive, the lengthening shadow of the vast dramatic irony that attended this whole matter—namely that it was precisely society’s most marginalized and oppressed people who truly understood what it might mean to live in a postapocalyptic world, and who were therefore most fully prepared—seemed to me to indicate a total moral incapacity.

I took her point to be that civilization was a relative concept to begin with, and that its collapse could seem to be more or less under way, depending on where you were standing.

The kind of freedom that was being invoked here was the freedom from government, which meant freedom from taxation and regulation, which in turn meant the freedom to act purely in one’s own interest, without having to consider the interests of others—which seemed to me the most bloodless and decrepit conception of freedom imaginable.

Once you start using the apocalypse as a way of encountering the present, an anxious response to uncertainty and change, it presents itself everywhere in the form of cryptic signals, deep emanations.

What they didn’t understand, she said, was that the thing that would allow people to survive was the same thing that had always allowed people to survive: community. It was only in learning to help people, she said, in becoming indispensable to one’s fellow human beings, that you would survive the collapse of civilization.

with doubtful hands to my own children? In the end, I understood that my fear of the collapse of civilization was really a fear of having to live, or having to die, like those unseen and mostly unconsidered people who sustained what we thought of as civilization.

The end of the world, I knew, was not some remote dystopian fantasy. It was all around. You just had to look.

But there are times when it seems that we are protecting him, and protecting ourselves, from a much deeper and more troubling truth: that the world is no place for a child, no place to have taken an innocent person against their will.

That act of switching off is, I realize, not without a certain political friction. Because if I want to teach my children anything, it is precisely not to switch off. What I want to teach them is to listen, to be aware, to consider their relative position in the world, and to be conscious of the ways in which others are less fortunate than they are, and crucially how it might be otherwise.

Lately I have been glad to be alive in this time, if only because there is no other time in which it’s possible to be alive. And I would think it a real shame, in the end, if there were nobody around to experience the world, because although it is a lot of other things, I would agree with my son that it is also an undeniably interesting place.