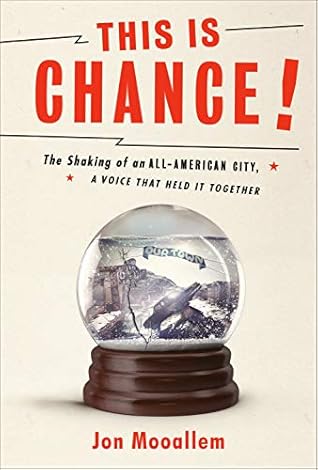

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Jon Mooallem

Read between

January 2, 2022 - October 27, 2024

The sociologists would spend a week in Anchorage after the quake, then make five subsequent trips to Alaska over the next eighteen months. They conducted nearly five hundred interviews, assembling a meticulous chronology of the immediate aftermath of the quake and reconstructing many of the same stories from Friday night and Saturday that you’ve already read in this book. Little of that action, they discovered, had unfolded methodically at all; it was all imprecise and instinctual.

SO MUCH OF WHAT the researchers learned in their interviews that week was only an elaboration of what Yutzy’s driver had told him shortly after he touched down: everybody in Anchorage had done a little bit of everything for everybody. It was startling, and cut against conventional wisdom’s predictions of savagery and hysteria. Yet for Enrico Quarantelli, it seemed only to be concrete confirmation of a wild idea he’d discovered years earlier.

Quarantelli was unique among the three founders of the Disaster Research Center in that he’d actually done research in disaster zones before. As a graduate student, he had worked at a government institute at the University of Chicago called the National Opinion Research Council, under the mentorship of a scholar named Charles Fritz. Fritz and several colleagues were broadening the council’s mission to examine human behavior in emergencies and disasters when Quarantelli came on board. Two years later, in 1952, they dispatched him on a field trip to White County, Arkansas, after the region was

...more

Fritz tried to synthesize what his team was learning from their fieldwork in an essay he called “Disasters and Mental Health.” “Disasters,” he wrote, “are, of course, occasions for profound human misery.” But they didn’t appear to create the chaos people feared.

“The notions that disaster survivors inevitably or typically engage in panic, looting, and scapegoating, or become helpless, hysterical, and neurotic simply do not stand the test of critical research scrutiny.” In fact, Fritz claimed, the people in those ruined communities seemed pretty happy. There might even be “therapeutic effects” to disasters, he argued—and from there, his speculations grew even more radical: “As social animals,” he wrote, “people perhaps come closer to fulfilling their basic human needs in the aftermath of disaster than at any other time.”

Fritz was arguing that disasters may bring out the best in human beings, rather than liberating some essential darkness in their nature. But at the time of the Good Friday Earthquake, Quarantelli was one of only a few people, even within the field of sociology, who would have been aware of that possibility. Fritz had written “Disasters and Mental Health” three years before the quake, as a chapter for an upcomi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

It was always a jarring discovery—and maybe most of all for Quarantelli and his colleagues from the Disaster Research Center, who, expecting to find the head of some elite military unit directing Anchorage’s search-and-rescue effort, instead discovered that the job had fallen to a self-deprecating and cerebral professor of the social sciences, just like them.

Quarantelli seemed fascinated by Davis and eager to understand how, exactly, he and his civilian mountaineers had managed to get so integrally involved. While some authority structures, like Civil Defense, appeared to have floundered after the quake, here was a totally informal group that had stepped in, organically, to pick up the slack. There were also brand-new ad hoc organizations like Disaster Control that had formed on the fly. The effectiveness of these improvised collectives was sharpening into focus for Quarantelli; it would be one of his primary takeaways from his time in Alaska. He

...more

everyone else was more or less the same: all coming to Alaska to effectively start again, or propelled out of the Lower 48 by some mounting, ineffable angst with conventional life that Davis found hard to pin down. (“I’d call it ‘American Disenchantment Syndrome,’ ” he said.) They were all here, sloshing around in one equitable middle class, none of them feeling particularly superior or inferior to anyone else. Davis believed this “excessive egalitarianism,” as he put it, served Anchorage during the emergency: encouraging camaraderie, discouraging violence. Moreover, he explained to

...more

This was all just one man’s rambling hypothesis, he told Quarantelli, but he suspected “there’s something fierce about the egalitarian attitudes of the people in Alaska that allowed them to work together in the disaster…And this idea that you’re grappling with hardship all the time—it minimized the panic.” Quarantelli and his colleagues would hear this theory frequently in Anchorage. The Alaskans were essentially arguing that the conventional wisdom about disasters was correct: they did bring out the worst in people—just not in Alaska, where people were simply kinder, tougher, and better

...more

The singular resilience of Alaskans came up often enough that Daniel Yutzy would be compelled to evaluate it in his final report on the earthquake, completed five years later. “These ‘frontier’ attitudes and analogies,” Yutzy wrote, “were constantly expressed to imply there was a special mystique of emotional resources which Anchorage had that would be absent in other American communities faced with similar problems.” And yet, Yutzy argued, most of what unfolded in Anchorage appeared to be merely typical human behavior, as already observed in other disasters, and as would continue to be

...more

Much of the sociologists’ work in Alaska would be incorporated into a landmark report on the disaster, commissioned by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Their studies of the earthquake would legitimize both the Disaster Research Center and the very idea of examining the social science of natural disasters. Gradually, an entire field—disaster studies—would blossom around Quarantelli and his colleagues and, as it grew, it would be stunning to recognize how much of what the sociologists had seen in Anchorage turned out to be characteristic of all disasters everywhere: People tended to act rationally,

...more

Looting was an exceedingly rare phenomenon after disasters, though paranoia about looting was always irrationally high. (In some cases, authorities are so overcome with worry about mass panic and looting that they preemptively clamp down on the public, even turning violently on innocent citizens who themselves aren’t actually panicked at all. Disaster scholars refer to this phenomenon as “elite panic.”) In short, our ugliest assumptions ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

After Quarantelli died, in 2017—at age ninety-two, a colossus of the field—a former student would remember hopping a flight to an earthquake-stricken region of Nicaragua and listening to Quarantelli lay out what he should expect to find once he got on the ground. The student was confused; Quarantelli spoke with a kind of offhanded authority, like he’d already been to Nicaragua and witnessed the scene for himself. He hadn’t, of course—the quake had only just occurred. But for Quarantelli, these kinds of random disasters had become some of the least surprising things on earth.

In fact, even Bill Davis’s assumption that Anchorage was atypical would turn out to be typical. Eventually, it would be possible to look back on disaster after disaster and recognize that so many communities tended to interpret their own levelheaded and altruistic conduct as exceptional—New Orleanians being New Orleanians, or Puerto Ricans being Puerto Ricans—instead of wholly consistent with a half century of rigorous social science. It would be hard to accept that our goodness is ordinary.

Gradually, they had collected the names of 330 people—all still potentially unaccounted for. Now, on the radio, they were asking anyone who lived in Turnagain to simply call in, hoping to scratch off whomever they could. The response was tremendous; the station’s phone lines sparked right away. People called in, reporting themselves safe or confirming the safety of others whom they’d taken into their homes. Four hours later, the Task Force sent its updated list to KENI: a hundred names remained.

Each name was read over the air, then read again at daybreak. And again, the number of potential casualties shrank rapidly as voices around Anchorage rose up, reached out, checked in. By Monday afternoon, the number of names on the Task Force’s list had dropped to fifty. By Monday evening, there were only sixteen names left. Ninety minutes after those names were broadcast, the list had been cut in half again.

The Task Force would stop clearing names off its list the following morning. Ultimately, one hundred and fifteen deaths were confirmed around the state of Alaska, the vast majority of them in the small communities that had been struck by tsunamis. But the final death toll in Anchorage was only nine.

Among the dead were the two Mead brothers from Turnagain, whose bodies were never found. A story surfaced that the older boy, Perry Jr., had died running back into the house to rescue his baby brother. But on the fiftieth anniversary of the earthquake, in 2014, the boys’ sister would explain to a reporter in Anchorage that the media must have invented that detail, to make the tragedy more palatable. The truth was, she had watched the earth swallow her brother Perry with her own eyes. Seconds later, determined to protect her two younger brothers, she’d lifted the first to safety on the roof of

...more

There was another reason, too, why the city’s search-and-rescue workers hadn’t kept finding more victims all weekend, like everyone had expected they would. As Genie interviewed more people in Anchorage, it became clear to her that the frenzied rescuers she’d seen digging in the rubble at Penney’s and peeling that woman out of her flattened car weren’t an anomaly. All over town, she wrote, “organized groups consisting of teachers, bankers, lawyers, laborers, bookkeepers—from all occupations and all walks of life—first methodically searched the ruins for survivors and fatalities.” There was the

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

AN OUTSIDE PSYCHOLOGIST WHO’D been visiting Alaska that Easter weekend later wrote an article describing how uncannily his experience of the disaster mirrored the description of another earthquake, written a half century earlier by the psychologist and philosopher William James. James was a New Englander who—similarly by chance—had been visiting California when the great San Francisco earthquake struck in April 1906. James astutely chronicled its aftermath in an essay he called “On Some Mental Effects of the Earthquake.”

Wandering around the city, James was left with two major impressions: “Both are reassuring as to human nature,” he wrote. “The first of these was the rapidity of the improvisation of order out of chaos.” James saw no panic, only purposefulness—people, “whether amateurs or officials, came to the front immediately” and got to work. “It was indeed a strange sight to see an entire population in the streets,” he explained, “busy as ants in an uncovered ant-hill scurrying to save their eggs and larvae.”

His second observation was less concrete, more spiritual. Even amid all that devastation, people seemed happy—even gleeful. Somehow, James wrote, the shattered city was overtaken by “universal equanimity.” He described people sleeping outside for several nights afterward, partly to keep safe from aftershocks, “but also to work off their emotion, and get the full unusualness out of the experience.” People felt a connection to one another, ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“Surely the cutting edge of all our usual misfortunates comes from their character of loneliness,” James wrote. In regular life, we suffer alone. But in San Francisco, each person’s “private miseries were merged in the vast general sum of privation.” As a result, to James, the victims didn’t seem like victims; they seemed empowered. He did not hear “a single whine or pla...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

This was also true in Anchorage. Many Alaskans discovered a peculiar joy in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, as they fed and sheltered neighbors, or huddled around a shared radio. There was camaraderie and altruism flowering everywhere. When, for example, the Alcantra family, who ran Alaska’s largest egg farm, on the outskirts of the city, discovered that the earthquake had spooked their hens out of laying, they invited the whole town to come and take home six or eight chickens apiece—meat with which to keep themselves fed through the emergency. The family claimed to have thirty

...more

It was as though daily life had suddenly separated from history. The fallibility and arbitrariness of absolutely everything was exposed, and other, more generous ways of being seemed possible.

After Sunday night, that heightened quality of the atmosphere in Anchorage began to dwindle. The disaster hadn’t ended; the city still had a slew of fearsome problems ahead of it—How would Anchorage pay for its reconstruction? How much help would the federal government provide? Was the ground even safe to rebuild on?—but those challenges were of a different magnitude, and far less straightforward, than the ones the community had been scrappily surmounting so far. Finding solutions to them—if solutions even existed—would take months, if not years, and involve towers of paperwork, recondite

...more

that fuss was in the future. In retrospect, that Sunday night would feel like a turning point, a hazy transition between one chapter of the disaster and the next. As the Task Force’s list of missing persons was recited over KENI and the responses streamed in over the phone, Anchorage appeared to be finishing off the last of its first kind of problems—the immediate and obvious ones that everyone in the community had been hacking through, collectively, since the moment the shaking started on Friday night. They were resolving the last, big question they were equipped to answer for themselves: Who

...more

there among the businessmen waiting on the tarmac, Bram noticed an unfamiliar face: “a typical urbane tourist type,” he said, who had somehow wound up on the last leg of their flight—slipping in like an apparition from the ordinary world. The man was complaining, obliviously and loudly enough for everyone around him to hear. He was griping about the lack of service. Bram couldn’t believe it. He watched the man flail, confronting the unimaginable: this upended, amenity-free reality into which he’d suddenly been dropped. Whatever was happening right now, Bram heard the man insisting, was the

...more

As soon as Genie entered the capitol building, a state senator recognized her and enthusiastically introduced her around. One after another, lawmakers kept thanking her. “They would shake hands or hug me, each with tears in their eyes,” she remembered. An unfamiliar energy seemed to be crackling in the air around her: the same prestige that would estrange her from her colleagues at KENI in the following months, then eventually get her elected to a seat in this very chamber. One lawmaker invited her to sit with him. And then, with all of Alaska listening, on a statewide radio hookup that Genie

...more

“Emma Gene,” she began sternly. “I am so concerned about health hazards in that area of impurities. Why don’t you get those children out of there!! The entire family should get out, at least until sewage is corrected all over the area. Come home and stay until conditions are not so conducive to pestilence. And if you don’t come yourselves, please send those children!” The kids’ well-being was paramount, Den insisted; Genie shouldn’t take any more chances with their safety. “Please do something,” she wrote.

Apparently the children must sense this, too. For they have remained calm. They have been fully aware of the emergency, but they have not feared. We are proud that they are such dependable, responsible youngsters. I would not undermine their confidence in the future—in themselves—by sending them away for safety. What is safety, anyway? How can you predict where or when tragedy will occur? You can only learn to live with it and make the best of it when it happens. These children have learned this—and they are all the better for it.

What is safety, anyway? Genie seemed to be conceding how randomly our lives are jostled and spun around, that nothing is fixed, that even the ground we stand on is in motion. Underneath us, there is only instability. Beyond us, there’s only chance. But she’d also recognized a way of surviving such a world.

It was what Genie had created in Anchorage that weekend by talking on the radio, and what she planned to stay focused on now: not an antidote to that unpredictability, exactly, but at least a strategy for withstanding it, for wringing meaning from a life we know to be unsteady and provisional. The best she and her family could do was to hold on to one another. Our force for counteracting chaos is connection.

Several months later, Mooallem would reach out to another of Brink’s acolytes in the Our Town cast, Bob Deloach—the young gay man with the coke-bottle glasses, who, in 2014, became one half of the first same-sex couple to legally marry in Alaska. When Deloach picked up the phone, Mooallem mentioned, by way of introduction, that he had already met with Deloach’s old friend Robert Pond. Deloach explained that Pond had just passed away.

Act I ended. Act II began. Before long, it was George and Emily’s wedding day, and the scene between Emily and her father that had blown up in rehearsals a few weeks earlier when the play’s prim and insecure lead, the beauty queen Susan Koslosky, fell apart in Brink’s office, worried she had no authentic self. Brink would continue to look out for Koslosky after the quake, finessing a grant application to qualify her for student housing, getting her out of her volatile mother’s house and into the university dorms. Eventually, Brink would encourage Koslosky to transfer to a small college in

...more

Emily was joining them to watch her own burial. But as the scene unfolded, she discovered she had the option of ineffably going back, somehow, and reliving moments from her life. The other souls pleaded with her not to; it’s too painful, they said. Finally, the Stage Manager explained why: “You not only live it,” he told her, “but you watch yourself living it. And as you watch it, you see the thing that they—down there—never know. You see the future. You know what’s going to happen afterwards.”

Emily couldn’t possibly understand these warnings. She wanted to go back. She chose an ordinary Tuesday morning fourteen years earlier, and suddenly, on Brink’s stage, the same timeless daily routine unfolded again: the mothers fixing breakfast in their neighboring houses, the milkman, the paperboy. Except this time, as Emily watched from one side of the stage and the audience watched through her eyes, the routine did not feel mundane at all, but precious and fleeting. The people living that life had no idea how fragile it was.

“Oh Mama,” Koslosky pleaded. “Just look at me one minute as though you really saw me. Mama, fourteen years have gone by. I’m dead.” But her mother couldn’t hear her. And the longer the scene played, the more wrenching her obliviousness became. “I can’t!” Koslosky finally told the Stage Manager, surrendering. “It goes so fast. We don’t have time to look at one another.”

In the darkness of the theater, Koslosky heard someone sobbing. She could feel a wave of vulnerability surge through the room. It felt to her as though the earthquake had broken everybody’s hearts open, and now this play—her lines—was pouring straight in. In retrospect, the parallel was clear: the disaster had shaken Anchorage out of its ordinary existence and into some shapeless, adjacent realm where, just like Emily, everyone could look back on their lives and appreciate the beauty and interconnectedness they hadn’t recognized before. But unlike Emily, the people in Anchorage had the

...more

Years later, Enrico Quarantelli would coauthor an article speculating about why the Disaster Research Center was documenting so little conflict in its studies of disaster-stricken communities around the world. In the paper, he compared a town coping with disaster to an audience watching a play. Like good theater, Quarantelli wrote, “disasters do not involve mundane matters but often the very issue of human life itself.” These themes, usually dormant in daily life, suddenly spill out in public for all to see. An unrelenting immediacy sets in: “Worries about the past and future are unrealistic

...more

Now, ten days after Anchorage’s disaster, Our Town appeared to be serendipitously bookending the experience, making some of those same epiphanies available to the community. A town that worried it was temporary had learned that it was temporary. But it was recognizing something permanent about itself, too.

Genie was not in the theater that night—not as far as Mooallem could tell, at least. There was no mention of Our Town in any of the documents Mooallem found in her daughter’s basement. The only item bearing that day’s date was a stray typewritten page—a kind of diary entry, it seemed, written after Genie had returned from Juneau with the governor and finally taken her first full day off since the quake. For nine days, she had pushed the stress and brutal imagery of the previous weekend out of her mind: that piece of a woman in the snow; the people downtown in every conceivable variety of

...more

He started picturing his own boxes. He imagined how many other boxes were already out there, in other people’s basements, and how many people hadn’t left boxes at all. Still, he clung to Genie’s story, as small as it ultimately might be, because it brought that profusion of other lives into focus, and because it suggested the unpredictable connections branching between them, or even reaching forward, unknowably, through time.