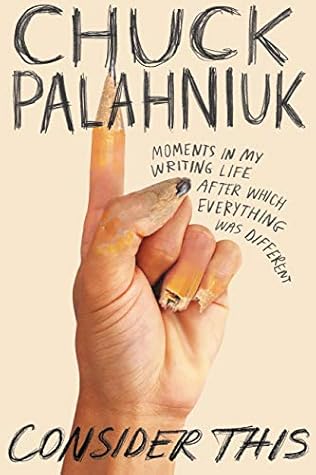

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

May 7 - July 13, 2020

“For anything to endure it must be made of either granite or words.”

At 23rd Avenue Books, Bob said, “If you want to make a career out of this you’ll need to bring out a new book every year. Never go longer than sixteen months without something new because after sixteen months people quit coming in that door and asking me if you have another book yet.” A book every year, I got it. The die was cast. Bob

“And another thing,” he cautioned me, “don’t use a lot of commas. People hate sentences with lots of commas. Keep your sentences short. Readers like short sentences.”

Most fiction consists of only description, but good storytelling can mix all three forms. For instance, “A man walks into a bar and orders a margarita. Easy enough. Mix three parts tequila and two parts triple sec with one part lime juice, pour it over ice, and—voilà—that’s a margarita.”

Using all three forms of communication creates a natural, conversational style. Description combined with occasional instruction, and punctuated with sound effects or exclamations: It’s how people talk.

Everyone should use three types of communication. Three parts description. Two parts instruction. One part onomatopoeia. Mix to taste.

If you were my student, I’d tell you to shift as needed between the three POVs. Not constantly, but as appropriate to control authority, intimacy, and pace.

Little voice gives us the facts. Big voice gives us the meaning—or at least a character’s subjective interpretation of the events. Not many stories exist without

In short, dialogue is your weakest storytelling tool. As Tom Spanbauer always taught us, “Language is not our first language.”

If you were my student I’d tell you to make a list of such placeholders. Find them in your own life. And find them in other languages, and among people in other cultures. Use them in your fiction. Cut fiction like film.

A part of the Ten Commandments of Minimalism: Don’t use Latinate words. Don’t use abstracts. Don’t use received text…And once you establish your authority, you can do anything.

Case closed. The smallest mistake can destroy all believability.

The job of the creative person is to recognize and express things for others. Some haven’t fully grasped their own feelings. Others lack the skill to communicate the feeling or idea. Still others lack the courage to express it.

Mona’s Law. It states that of a great lover, a great job, and a great apartment, in life you can have one. At most you can have two of the three. But you will never, ever have all three at the same time.

aphorism

wise, intuitive observation can convey more power than all the facts in Wikipedia.

Now if I were your teacher, I’d tell you to write a story in which a jaded on-air appraiser is asked to confirm the value of a cursed monkey’s paw…a shrunken head…the Holy Grail.

Witness the movies that premiered to damning reviews. The Night of the Living Dead. Harold and Maude. Blade Runner. They found a place in public memory, and time has made them classics. So do not write to be liked. Write to be remembered.

How do you convince a reader of something beyond his own experience? You start with what he does know, and you move in baby steps toward what he doesn’t. One of my favorite examples of this comes from the novel The Contortionist’s Handbook by Craig Clevenger. To paraphrase, he tells the reader to imagine waking up on a Monday morning filled with dread. Another stultifying week looms. Another soul-crushing day at work, doing something you’d never planned to do for the rest of your life. You’re growing older, your life wasted, your dreams lost. And then you realize it’s actually Sunday morning.

...more

If you were my student I’d tell you to read the story “The Enormous Radio” by John Cheever. Then read “Call Guy” by Alec Wilkinson in The New Yorker. Then imagine some kid ordering the typical X-ray specs from an ad in the back of a comic book. The precedent exists for the omniscient device.

Always, always, if you were my student, I’d tell you to allow the epiphany to occur in the reader’s mind before it’s stated on the page.

So never dictate meaning to your reader. If need be, misdirect him. But always allow him to realize the truth before you state it outright. Trust your readers’ intelligence and intuition, and they will return the favor.

It felt good to fall apart. The first step to being schooled toward some greater knowledge.

The trouble is that readers recoil from the pronoun “I” because it constantly reminds them that they, themselves, are not experiencing the plot events. We hate that, when we’re stuck listening to someone whose stories are all about himself. The fix is to use first person, Peter taught me, but to submerge the I. Always keep your camera pointed elsewhere, describing other characters. Strictly limit a narrator’s reference to self. This is why “apostolic” fiction works so well. In books like The Great Gatsby the narrator acts mostly to describe another, more interesting, character. Nick is an

...more

So were I your teacher, I’d tell you to write in the first person, but to weed out almost all of your pesky “I”s.

My point is that people measure stuff—money, strength, time, weight—in very personal ways. A city isn’t so many miles from another city, it’s so many songs on the radio. Two hundred pounds isn’t two hundred pounds, it’s that dumbbell at the gym that no one touched and that seemed like a sword-in-the-stone joke until the day a stranger took it off the rack and started doing single-arm rows with it.

As Katherine Dunn put it, “No two people ever walk into the same room.”

I’d ask you: What strategy has your character chosen for success in life? What education or experiences does he or she bring? What priorities? Will they be able to adopt a new dream and a new strategy? Every detail they notice in the world will depend on your answers to the above questions.

“When you don’t know what comes next, describe the interior of the narrator’s mouth.”

I paid him three $50 bills and left vibrating with shame about talking too much and saying nothing significant while resenting how he’d said almost nothing.

So if you were my student, I’d tell you to listen to your body as you write. Take note how your hand knows how much coffee is left by the weight of the cup. Tell your stories not simply through your readers’ eyes and minds, but through their skin, their noses, their guts, the bottoms of their feet.

The lesson is: if you can identify the archetype your story depicts, you can more effectively fulfill the unconscious expectations of the reader.

If you can identify the core legend that your story is telling, you can best fulfill the expectation of the legend’s ending.

At that the reader is stunned, but “heart authority” is created. We know the writer isn’t afraid to tell an awful truth. The writer might not be smarter than us. But the writer is braver and more honest. That’s “heart authority.”

A character’s mistake or misdeeds allow the reader to feel smarter. The reader becomes the caretaker or parent of the character and wants the character to survive and succeed.

So if you were my student, I’d tell you to establish emotional authority by depicting an imperfect character making a mistake.

As Ira Levin saw it, “Great problems, not clever solutions, make great fiction.”

“The longer you can be with the unresolved thing, the more beautifully it will resolve itself.”

One way that Minimalist writing creates the vertical effectively is by limiting the elements within a story. Introducing an element, say a new character or setting, requires descriptive language. Passive language. So by introducing limited elements, and doing so early, the Minimalist writer is free to aggressively move the plot forward. And the limited number of elements—characters, objects, settings—accrue meaning and importance as they’re used repeatedly.

So if you were my student I’d tell you to limit your elements and make certain each represents one of the horses your story is about. Find a hundred ways to say the same thing.

If your stories tend to amble along, lose momentum, and fizzle out, I’d ask you, “What’s your clock?” And, “Where’s your gun?”

“Berlin runs by many clocks,” meaning people have many options and they won’t commit to one until the last moment.

In fiction the clock I’m talking about is anything that limits the story’s length by forcing it to end at a designated time.

So, my student, today’s lesson is to recycle your objects. Introduce them, then hide them. Rediscover them, then hide them. Each time you bring them back, make them carry greater importance and emotion. Recycle them. In the end, resolve them beautifully.

Always keep in mind our tendency to avoid conflict (we’re writers) and to cheat and use dialogue to further plot (a cardinal sin).

After I left the stage Ursula sought me out. We’d never met, but she wanted to help me brainstorm a better ending. Doing so she told me, “Never resolve a threat until you raise a larger one.”

If a plot point is worth including, it’s worth depicting in a scene. Don’t deliver it in dialogue.

Is he really going to go there? Is this guy actually going to describe a kid giving an old man a blow job? And Williams did. He didn’t redirect to something safer, for example having the narrator distract himself with the comforting childhood memory of eating a nice hot dog on July 4. Nor did he jump ahead to a future scene and recount the sex using dialogue or tasteful snippets of memory. Nope, the writer unpacked the details and read them in public to a crowd. Tom admired him for having the courage to write the tough stuff. And to read it. And if you were my student I’d tell you that that is

...more

To quote Joy Williams, “You don’t write to make friends.”

But good writing is not about making the writer look good.