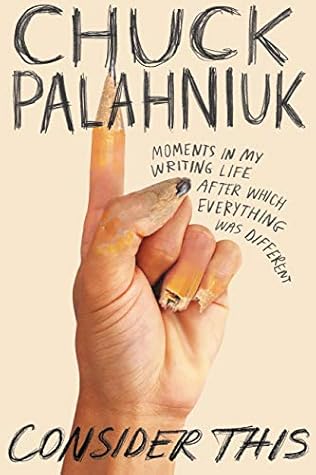

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 6 - January 17, 2022

If you were my student I’d tell you about the first writing exercise Tom Spanbauer typically assigned his writers. He’d tell them, “Write about something you can hardly remember.” They’d start with a scent. A taste. One tangible physical detail would elicit another. It was as if their bodies were recording devices far more effective than their minds. To repeat: Your body is a recording device more effective than your mind.

So if you were my student, I’d tell you to listen to your body as you write. Take note how your hand knows how much coffee is left by the weight of the cup. Tell your stories not simply through your readers’ eyes and minds, but through their skin, their noses, their guts, the bottoms of their feet.

The lesson is: if you can identify the archetype your story depicts, you can more effectively fulfill the unconscious expectations of the reader.

If you can identify the core legend that your story is telling, you can best fulfill the expectation of the legend’s ending.

the shift to third person implies self-loathing or disassociation or both.

I’d tell you to establish emotional authority by depicting an imperfect character making a mistake.

My solution? To order wholesale. Arms, legs, hands, feet. By the cardboard caseload from slave labor factories in China.

I’m really not a tactless dick, but maybe I ought to start to think more things through.

“Great problems, not clever solutions, make great fiction.”

“The longer you can be with the unresolved thing, the more beautifully it will resolve itself.”

It takes some practice to create, sustain, and increase chaos, and trust that you can also resolve it.

In workshop Tom Spanbauer would always lecture about the horizontal and the vertical of a story. The horizontal refers to the sequence of plot points:

The vertical refers to the increase in emotional, physical, and psychological tension over the course of the story. As the plot progresses so should the tension ramp up. Minus the vertical, a story devolves to “and then, and then, and then.”

One way that Minimalist writing creates the vertical effectively is by limiting the elements within a story. Introducing an element, say a new character or setting, requires descriptive language. Passive language. So by introducing limited elements, and doing so early, the Minimalist writer is free to aggressively move the plot forward. And the limited number of elements—characters, objects, settings—accrue meaning and importance as they’re used repeatedly.

Find a hundred ways to say the same thing.

I’d tell you to watch television commercials.

Unconventional Conjunctions

I’d urge you to cut your narrative like a film editor cuts film.

Thus cuing the reader with a sort-of touchstone that indicates: We’re about to jump to something different.

Listen to someone who’s terrified of being interrupted and has developed tricks for hogging a listener’s attention nonstop.

That’s what I call recycling an object in a story. The reader is thrilled to recognize something that seemed lost. And because the object is not a character and can’t have an emotional reaction, the reader is forced to express any related emotion.

Now consider the dog, Sorrow, in The Hotel New Hampshire. It dies. It’s stuffed by a taxidermist. It falls from an exploding jetliner. Washes up on a beach. Is found and dried with a hair dryer. Wrecks a sexual tryst. Hidden away, it’s eventually found and prompts a heart attack. The dog’s name alone prompts a major chorus in the book: “Sorrow floats.”

In a forensic unpacking of the era, green was a popular color, deep green, because rooms decorated in emerald green seldom harbored houseflies or fleas, spiders or any other pests. For some miraculous reason you could leave windows open and green drapes seemed to repel mosquitoes. Families such as the O’Haras could lounge in their deep-green sanctuaries, unbothered by yellow-fever-carrying insects. Unknown at the time, emerald green or “Paris Green” dyes contained heavy amounts of arsenic. The deeper the color, the more poisonous the fabric. Up to half the velvet’s weight could be arsenic,

...more

So, my student, today’s lesson is to recycle your objects. Introduce them, then hide them. Rediscover them, then hide them. Each time you bring them back, make them carry greater importance and emotion. Recycle them. In the end, resolve them beautifully.

If you were my student I’d tell you to be clever on someone else’s dime.

Cleverness is a brand of hiding. It will never make your reader cry. It seldom makes readers genuinely belly laugh and never breaks anyone’s heart.

Instead, if you were my student I’d tell you to never resolve an issue until you introduce a bigger one.

Always keep in mind our tendency to avoid conflict (we’re writers) and to cheat and use dialogue to further plot (a cardinal sin). So to do the first and avoid the second, use evasive dialogue or miscommunications to always increase the tension. Avoid volleys of dialogue that resolve tension too quickly.

“Never resolve a threat until you raise a larger one.”

If a plot point is worth including, it’s worth depicting in a scene. Don’t deliver it in dialogue.

It sounds harsh, but I forbid you from furthering your plot with dialogue. To do so is cheap and lazy.

So unpack the big stuff. Do not deliver important information via dialogue.

Gordon Lish forbid depicting dreams in fiction. His thinking, as I understood it, was that dream sequences are a cheat. Reality can be just as surreal.

Arbitrary as it might sound, nobody wants to hear about your dream from last night.

And avoid abstract verbs in favor of creating the circumstances that allow your reader to do the remembering, the believing, and the loving. You may not dictate emotion. Your job is to create the situation that generates the desired emotion in your reader.

I depict questionable behavior in my work but refuse to endorse or condemn it.

Advances in medicine saved the lives of many soldiers who never would’ve come home from earlier wars. And these severely mutilated survivors occasionally appeared in public. These horror films gave audiences a scare, but they also allowed them to acclimate to the sight of “monsters.”

They offer the chaos and illogic of Kafka, but with the humor of satire.

Write as if you were the collective voice of a film review board that’s been asked to assign an audience rating to a yet-to-be-released movie. Speaking in the collective “we” you cite increasingly absurd inferences the board members believe they are seeing. Clouds that look too phallic for comfort. The maybe-not-accidental way that shadows cast by people and animals combine and interact. Doughnuts being eaten by children in a possibly suggestive manner. In your report to the filmmaker, you cite how individual viewers first recognized each transgression, but when it was pointed out all

...more

Anytime you deny a possibility you create it at the same time.

As a writer, anytime you want to introduce a threat, assure the reader that it won’t happen.

Once, a friend at my day job said, “I see the way you think things are.” Such a wonderful-sounding sentence, full of echoes and ambiguity.

The ticket agent shrugged, cheerfully saying, “I’ve never done it that way. Let’s see what happens.” Again, such a wonderful sentence, so filled with curiosity and anticipation.

“Dude, I love the way you keep the mud alive!”

“New Englanders, God’s frozen people.”

build your novel with a number of scenes or chapters that can stand alone as short stories. Magazines and websites can excerpt these, and they make a much better advertisement for your book. Plan for the fact that every medium wants free content.

A painter once told me that any artist must manage her life to create large blocks of time for creative work. By making ongoing notes throughout my day, when I finally do sit down to “write” I have a pile of ideas. I’m not wasting any of my valuable creative time by starting from zero.

Because it creates a shared baseline experience that will someday be a comfort. In the future, no matter how many beautiful little puppies or kittens die under your care, no matter how heart wrenching your job might feel, it will never feel as horrible as waking up inside a cold, dead horse.

The best stories evoke stories.

Similarly, John Steinbeck’s method was to listen at the fringes. To study how people spoke and to learn the details of their lives. He panicked once he became famous. As the center of attention he could no longer gather what he needed.