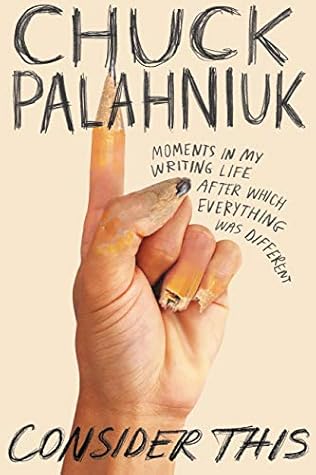

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 9 - July 17, 2020

If you’re dedicated to becoming an author, nothing I can say here will stop you. But if you’re not, nothing I can say will make you one.

I’d paraphrase the writer Joy Williams, who says that writers must be smart enough to hatch a brilliant idea—but dull enough to research it, keyboard it, edit and re-edit it, market the manuscript, revise it, revise it, re-revise it, review the copy edit, proofread the typeset galleys, slog through the interviews and write the essays to promote it, and finally to show up in a dozen cities and autograph copies for thousands or tens of thousands of people… And then I’d tell you, “Now get off my porch.” But if you came back to me a third time, I’d say, “Kid…” I’d say, “Don’t say I didn’t warn

...more

Avoid making your reader feel foolish at all costs! You want to make your reader feel smart, smarter than the main character. That way the reader will sympathize and want to root for the character.

Cut fiction like film.

Tom Spanbauer always said, “Writers write because they weren’t invited to a party.” So bear in mind that the reader is also alone. A reader is more likely to feel socially awkward and crave a story that offers a way to be in the company of others. The reader, alone in bed or alone in an airport crowded with strangers, will respond to the party scenes at Jay Gatsby’s mansion.

To heighten this ritual effect, consider creating a “template” chapter. Using one existing chapter, change minor details and make it arrive at a fresh epiphany. Chances are the reader won’t realize what you’ve done, but will unconsciously recognize the repeated structure. Use this template to create three chapters placed equal distances apart in the book. In this world where so many fraternal organizations and religions are disappearing, if you were my student I’d tell you to use ritual and repetition to invent new ones for your readers. Give people a model they can replicate and characters to

...more

Make the reader believe you. Make the incredible seem inevitable.

focus on breaking down a gesture and describing it so effectively that the reader unconsciously mimics it. Not everything, but the crucial objects and actions should be unpacked. In Shirley Jackson’s story “The Lottery,” note how she lingers on the box from which the papers are drawn. She describes where it’s stored, how it was crafted, what it replaced. All of this attention lavished on a plain wooden box helps us accept the horrible purpose for it. If we believe in the box, we’ll believe the ritual murder it facilitates.

Witness the movies that premiered to damning reviews. The Night of the Living Dead. Harold and Maude. Blade Runner. They found a place in public memory, and time has made them classics. So do not write to be liked. Write to be remembered.

Instead of writing about a character, write from within the character. This means that every way the character describes the world must describe the character’s experience. You and I never walk into the same room as each other. We each see the room through the lens of our own life. A plumber enters a very different room than a painter enters. This means you can’t use abstract measurements. No more six-foot-tall men. Instead you must describe a man’s size based on how your character or narrator perceives a man whose height is seventy-two inches. A character might say “a man too tall to kiss” or

...more

Don’t pretend for a moment that writing as a different person is evading reality. If anything it allows you a greater freedom to explore parts of yourself you wouldn’t dare consciously examine.

While researching for my book Rant I attended a seminar for used car salespeople. In it the instructor explained that people are usually one of three types: the visual, the auditory, or the tactile. The visual will preface each statement with visual terms. “Look here…” or “I see, but…” The auditory will use terms based on hearing: “Listen up…” or “I hear what you’re saying.” The tactile will use physical, active terms: “I catch your drift,” or, “I can’t wrap my mind around it.” Bullshit or not, it’s a good place to start. Which way will your character skew?

Beyond that, no abstracts (no inches, miles, minutes, days, decibels, tons, lumens) because the way someone depicts the world should more accurately depict him.

How do you convince a reader of something beyond his own experience? You start with what he does know, and you move in baby steps toward what he doesn’t.

Always, always, if you were my student, I’d tell you to allow the epiphany to occur in the reader’s mind before it’s stated on the page.

use first person, Peter taught me, but to submerge the I. Always keep your camera pointed elsewhere, describing other characters. Strictly limit a narrator’s reference to self. This is why “apostolic” fiction works so well. In books like The Great Gatsby the narrator acts mostly to describe another, more interesting, character. Nick is an apostle of Gatsby, just as the narrator of Fight Club is an apostle of Tyler Durden. Each narrator acts as a foil—think of Dr. Watson gushing about Sherlock Holmes—because a heroic character telling his own story would be boring and off-putting as hell. In

...more

Actually, it’s more interesting if a character views the world through a mistake.

As the writer Matthew Stadler advises, “When you don’t know what comes next, describe the interior of the narrator’s mouth.” He was joking, but he wasn’t. If done well, this prompts a similar reaction in the reader’s body. With that complete, you can shift back to describing the scene, or intercut with a big-voice observation, or add a new stressor, or whatever you think will best keep up the tension of the moment.

If you were my student I’d tell you about the first writing exercise Tom Spanbauer typically assigned his writers. He’d tell them, “Write about something you can hardly remember.” They’d start with a scent. A taste. One tangible physical detail would elicit another. It was as if their bodies were recording devices far more effective than their minds. To repeat: Your body is a recording device more effective than your mind.

So if you were my student, I’d tell you to listen to your body as you write. Take note how your hand knows how much coffee is left by the weight of the cup. Tell your stories not simply through your readers’ eyes and minds, but through their skin, their noses, their guts, the bottoms of their feet.

The lesson is: if you can identify the archetype your story depicts, you can more effectively fulfill the unconscious expectations of the reader.

If you can identify the core legend that your story is telling, you can best fulfill the expectation of the legend’s ending.

A character’s mistake or misdeeds allow the reader to feel smarter. The reader becomes the caretaker or parent of the character and wants the character to survive and succeed.

So if you were my student, I’d tell you to establish emotional authority by depicting an imperfect character making a mistake.

“The longer you can be with the unresolved thing, the more beautifully it will resolve itself.”

So if you were my student I’d tell you to limit your elements and make certain each represents one of the horses your story is about. Find a hundred ways to say the same thing. For example, the theme in my book Choke is “things that are not what they appear to be.” That includes the clocks that use birdcalls to tell the time, the coded public address announcements, the fake choking man, the historical theme park, the fake doctor “Paige.” I’d tell you to watch television commercials. See how they never show you a fat person eating at Domino’s or Burger King? Watch how they ramp up the vertical

...more

In my novel Survivor, told aboard a jetliner that will eventually run out of fuel and crash, time is marked by each of the four engines flaming out. They mark the end of the first act, the second act, the third act, and the end of the book. Friends of mine hated how the diminishing number of pages betrayed how soon a book would end. And because I couldn’t change that aspect of a book, I chose to accentuate it. By running the page numbers in reverse I made them into another clock, increasing tension by exaggerating the sense of time passing.

A gun is a different matter. While a clock is set to run for a specified time period, a gun can be pulled out at any moment to bring the story to a climax. It’s called a gun because of Chekhov’s directive that if a character puts a gun in a drawer in act 1 he or she must pull it out in the final act. A classic example is the faulty furnace in The Shining. We’re told early on that it will explode. The story might stagger on until springtime, but for the fact that…the furnace explodes.

Whereas a clock is something obvious and constantly brought to mind, a gun is something you introduce and hide, early, and hope your audience will forget. When you finally reveal it, you want the gun to feel both surprising and inevitable. Like death, or the orgasm at the end of sex.

For now if you came to me and said your novel was approaching eight hundred pages with no sign of ending, I’d ask, “What’s your clock?” I’d ask, “Did you plant a gun?” I’d tell you to kill your Red Buttons or Big Bob and to bring your fictional world to a messy, noisy, chaotic climax.

If you were my student, I’d tell you to recycle your objects. This means introducing and concealing the same object throughout the story. Each time it reappears, the object carries a new, stronger meaning. Each reappearance marks an evolution in the characters.

So, my student, today’s lesson is to recycle your objects. Introduce them, then hide them. Rediscover them, then hide them. Each time you bring them back, make them carry greater importance and emotion. Recycle them. In the end, resolve them beautifully.

Always keep in mind our tendency to avoid conflict (we’re writers) and to cheat and use dialogue to further plot (a cardinal sin). So to do the first and avoid the second, use evasive dialogue or miscommunications to always increase the tension. Avoid volleys of dialogue that resolve tension too quickly.

After I left the stage Ursula sought me out. We’d never met, but she wanted to help me brainstorm a better ending. Doing so she told me, “Never resolve a threat until you raise a larger one.” Ursula K. Le Guin

With that in mind, I’d tell you to avoid “is” and “has” in any form. And avoid abstract verbs in favor of creating the circumstances that allow your reader to do the remembering, the believing, and the loving. You may not dictate emotion. Your job is to create the situation that generates the desired emotion in your reader.

In old-fashioned literary terms, anytime you broach a subject yet refuse to explore it, that’s called occupatio (in Greek paralipsis). For example, “The first rule of fight club is you don’t talk about fight club.” But the technique also covers statements such as, “You know I’d never kill you, don’t you?” Or, “He told himself not to slap her.” Anytime you deny a possibility you create it at the same time. Such statements introduce the threat they appear to be denying. For instance: This ship is unsinkable. The canned salmon is supposed to be safe. Please don’t mention Daniel’s murder. We’re

...more

Ira Levin’s point being: don’t overthink your creative process.

I think of myself as a conduit. I am the disposable thing trying to identify the eternal thing. Experience enters and product exits.

A painter once told me that any artist must manage her life to create large blocks of time for creative work.

This arduous process of creating a complete first draft, Tom calls it “shitting out the lump of coal.” As in, “Relax, you’re still shitting out your lump of coal.”

Tom’s use of “manumission” meant the grace with which your sentences carried the reader forward without disturbing the fictional dream. To demonstrate this, he’d cup his hands and tilt them as if gently passing a small object back and forth between his palms. A good writer must gently pass the reader from sentence to sentence, like a fragile egg, without jarring the reader out of the story.

To create this community, give readers more than they can handle alone. Give them so much humor or pathos or idea or profundity that they’re compelled to push the book on others if only to have peers with whom they can discuss it. Give them a book so strong, or a performance so big, that it becomes a story they tell. It’s their story about experiencing the story.

You see, the secret is to trick yourself into having a great time. Whether you’re on a twenty-city book tour or washing dishes, find some way to love the task. In fact there’s a Buddhist saying told to me by Nora Ephron, the one-and-only time I met her after reading her work since college. At a noisy Random House party in the restaurant Cognac, she said, “If you can’t be happy while washing dishes, you can’t be happy.”

And don’t imagine I’d ever pass up such a crowd-pleasing structure. Fight Club might appear to have only two main characters, Tyler and the narrator. But the good-boy narrator still commits suicide. And the bad-boy rebel is still executed. And both acts integrate the two to create the third, the wise witness left to tell us what happened. The lesson? Don’t be too passive. And don’t be too pushy. Watch and learn from the extremes of other people. That’s our favorite American sermon. And boy howdy does it sell books!

Then I’d tell you the opposite. Don’t perpetuate the status quo. Let Nick Carraway shout “You’re a bag of dicks!” at Tom and Daisy, and “Daisy slaughtered Myrtle!” Let Jay Gatsby leap from his pool and grab the gun. What is our preoccupation with defeat? Why do high-art narratives end poorly? Is it the destruction of the Greek comedies and the Christian church’s obsession with tragedy? If more writers strove for paradigm-busting resolutions, would there be less suicide and addiction among writers? And readers? Above all, I’d tell you, do not use death to resolve your story. Your reader must

...more

This is another reason to bother collecting stories. Because our existence is a constant flow of the impossible, the implausible, the coincidental. And what we see on television and in films must always be diluted to make it “believable.” We’re trained to live in constant denial of the miraculous. And it’s only by telling our stories that we get any sense of how extraordinary human existence actually can be. To shut yourself off from these stories is to accept the banal version of reality that’s always used to frame advertisements for miracle wrinkle creams and miracle diet pills. It’s as if

...more

When you meet a reader, it’s your turn to listen.”

You have to talk, otherwise your head turns into a cemetery. I called out, “That is a great coat!”

Problem: Your work fails to attract an agent, editor, or audience. Consider: Does that really matter? If writing is fun…if it exhausts your personal issues…if it puts you in the company of other people who enjoy it…if it allows you to attend parties and share your stories and enjoy the stories told by others…if you’re growing and experimenting with every draft…if you’d be happy writing for the rest of your life, does your work really need to be validated by others?

If you were my student I’d ask you to consider just one more possibility. What if all of our anger and fear is unwarranted? What if world events are unfolding in perfect order to deliver us to a distant joy we can’t conceive of at this time? Please consider that the next ending will be the happy one.