More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Behind the Gypsy, at the curb, in a no-parking zone, stood a huge old pickup truck with a homemade camper cap. The cap was covered with strange designs around a central painting—a not-very-good rendering of a unicorn on its knees, head bowed, before a Gypsy woman with a garland of flowers in her hands. The Gypsy man had been wearing a green twill vest, with buttons made out of silver coins.

They were brightly dressed, but not in the peasant garb an older person might have associated with the Hollywood version of Gypsies in the thirties and forties. There were women in colorful sundresses, women in calf-length clamdigger pants, younger women in Jordache or Calvin Klein jeans. They looked bright, alive, somehow dangerous.

Two teenage Gypsy boys of approximately Linda’s age popped out of an old LTD station wagon and began to scruff the spent ammunition out of the grass. They were alike as two peas in a pod, obviously identical twins. One wore a gold hoop in his left ear; his brother wore the mate in his right. Is that how their mother tells them apart? Billy thought.

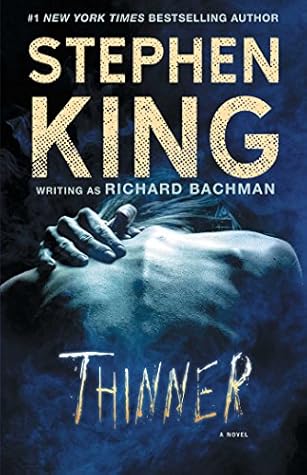

“No. And, Billy, I don’t exactly consider pimples off-the-wall. You were starting to sound a little like a Stephen King novel for a while there, but it’s not like that. Dunc Hopley has got a temporary glandular imbalance, that’s all. And it’s not exactly a new thing with him, either. He has a history of skin problems going back to the seventh grade.” “Very rational. But if you add Cary Rossington with his alligator skin and William J. Halleck with his case of involuntary anorexia nervosa into the equation, it starts to sound a little like Stephen King again, wouldn’t you say?”

He had been fat—not bulky, not a few pounds overweight, but downright pig-fat. Then he had been stout, then just about normal (if there really was such a thing—the Three Stooges from the Glassman Clinic seemed to think there was, anyway), then thin. But now thinness was beginning to slip into a new state: scrawniness. What came after that? Emaciation, he supposed. And after that, something that still lingered just beyond the bounds of his imagination.

“Tell me something, Richard—are you superstitious?” “Me? You ask an old wop like me if I’m superstitious? Growing up in a family where my mother and grandmother and all my aunts went around hail-Marying and praying to every saint you ever heard of and another bunch you didn’t ever hear of and covering up the mirrors when someone died and poking the sign of the evil eye at crows and black cats that crossed their path? Me? You ask me a question like that?” “Yeah,” Billy said, smiling a little in spite of himself. “I ask you a question like that.” Richard Ginelli’s voice came back, flat, hard,

...more

“Taduz Lemke,” Penschley said calmly. “The father of the woman you struck with your car. Yes, he’s with them.” “Father?” Halleck barked. “That’s impossible, Kirk! The woman was old, around seventy, seventy-five—” “Taduz Lemke is a hundred and six.” For several moments Billy found it impossible to speak at all. His lips moved, but that was all. He looked like a man kissing a ghost. Then he managed to repeat: “That’s impossible.” “An age we all could certainly envy,” Kirk Penschley said, “but not at all impossible. There are records on all of these people, you know—they’re not wandering around

...more

To Billy Halleck’s fascinated, dismayed eyes, everyone seemed overweight and everyone—even the skateboard kids—seemed to be eating something: a slice of pizza here, a Chipwich there, a bag of Doritos, a bag of popcorn, a cone of cotton candy. He saw a fat man in an untucked white shirt, baggy green Bermudas, and thong sandals gobbling a foot-long dog. A string of something that was either onion or sauerkraut hung from his chin. He held two more dogs between the pudgy fingers of his left hand, and to Billy he looked like a stage magician displaying red rubber balls before making them disappear.

Enders had known everyone associated with the summer carnival that was Old Orchard, it seemed—the vendors, the pitchmen, the roustabouts, the glass-chuckers (souvenir salesmen), the dogsmen (ride mechanics), the bumpers, the carnies, the pumps and the pimps. Most of them were year-round people he had known for decades or people who returned each summer like migratory birds. They formed a stable, mostly loving community that the summer people never saw.

“Dogfight!” “People want to bet, my friend, and drift trade is always willing to arrange the things they want to bet on—that’s one of the things drift trade is for. Dogs or roosters with steel spurs or maybe even two men with these itty-bitty sharp knives that look almost like spikes, and each of ’em bites the end of a scarf, and the one who drops his end first is the loser. What the Gypsies call ‘a fair one.’ ” Enders was staring at himself in the back bar mirror—at himself and through himself. “It was like the old days, all right,” he said dreamily. “I could smell their meat, the way they

...more

“Flash was what they used to call me when I worked the pennypitch on the pier back in the fifties, my friend, but nobody has called me that for years. I was way back in the shadows, but he saw me and he called me by my old name—what the Gypsies would call my secret name, I guess. They set a hell of a store by knowing a man’s secret name.”

It wasn’t the out-of-state plates; there were lots of out-of-state plates to be seen in Maine during the summer. It was the way the cars and vans traveled together, almost bumper to bumper; the colorful pictures on the sides; the Gypsies themselves. Most of the people Billy talked to claimed that the women or children had stolen things, but all seemed vague on just what had been stolen, and no one, so far as Billy could ascertain, had called the cops because of these supposed thefts.

The eyes of age, had he thought? They were something more than that . . . and something less. It was emptiness he saw in them; it was emptiness which was their fundamental truth, not the surface awareness that gleamed on them like moonlight on dark water. Emptiness as deep and complete as the spaces which may lie between galaxies.

“But I guess I have to do something. After all, I cursed him.” “So you told me. The curse of the white dude from town. Considering what all the white dudes from all the towns have done in the last couple hundred years, that could be a pretty heavy one.”

“Are you saying God is on your side?” she asked him, her voice so thick the words were almost unintelligible. “Is that what I hear you saying? You should burn in hell for such blasphemy. Are we hyenas? If we are, it was people like your friend who made us so. My great-grandfather says there are no curses, only mirrors you hold up to the souls of men and women.”