More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It occurred to me in that moment to question why, as a man, his bare legs were somehow less troubling than mine. It was a double standard, a shame I had simply accepted until then. In acquiring my gender, I had become offensive.

The last line was the hardest to read, the one that made my throat burn: “Maybe one day you’ll learn you can’t treat people with such disregard. Even yourself.”

Without the security of a relationship, longing felt less safe. It felt lonely.

These were my first images of the conflict that shattered our homeland and scattered my family. Terms like civilian casualties and Molotov cocktails and cease-fire, later replaced by negotiations and peace talks and Camp David, resounded in the Peter Jennings voiceovers as the footage of violence played on screen. We watched at a cool remove while enjoying the comforts of our American suburb, seemingly untouched, oblivious of the underlying trauma.

The notion that everyone will eventually cease to exist brings me great comfort and temporary courage.

I stared at the clock as the minute hand eclipsed the hour hand for the third time and decided that only a white man would feel comfortable taking up so much space.

If my mother was Hamas—unpredictable, impulsive, and frustrated at being stifled—my father was Israel. He’d refuse to meet her most basic needs until she exploded. Then he would point at her and cry, “Look at what a monster she is, what a terror!” But never once did he consider why she had resorted to such extreme tactics, or his role in the matter.

Some of my strongest memories of my father involve him weeding the garden or watching television. He did not want to be bothered, especially not by his immediate family. Activities that allowed him to completely shut out our needs and emotions seemed to resonate with him.

He would tutor me in Arabic, he’d show up to Karim’s soccer games, he’d sing me awake. But the things that we craved most, like fatherly guidance or af...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“I have no responsibilities here,” I said. “And no ties to anyone.” He smiled, and his white beard spread like smoke. “You’ll find that having someone who has a claim on you, and who you can claim, it’s one of the greater things in life.”

Molly shook her head and smiled. “Read all you want,” she said with uncharacteristic authority. “But you’ll just end up a more informed prisoner.”

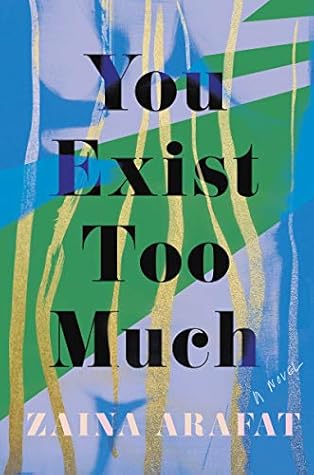

I sniffled and snorted and tried to suck back snot and tears, which only made me cry harder. I’m aware I can be exhausting—“you exist too much,” my mother often told me.

She was born in between two catastrophic years in Palestine’s history: ’48 and ’67. The Six-Day War broke out when she was eight years old. In less than a week, Jordan, Egypt, and Syria lost control of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula. Another wave of Palestinian displacement ensued. The possibility of a state called Palestine receded even further into the distance, becoming nearly unattainable.

She recalls that on weekends, she and her four siblings would travel through three checkpoints from Nablus to Ramallah, for two scoops each of pistachio ice cream at Rookab.

“The thing about education,” her father told her the day of her college graduation, which coincided with a sharp increase in Israeli settlement construction on confiscated land in the West Bank, “is that no one can take it away from you. Everything else can be stolen. Everything else can be lost.”

Appetite is embarrassing enough; visibly trying to satiate it, utterly mortifying.