More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Barack Obama

Read between

April 24 - April 30, 2020

As black businesses and commercial strips struggled, Latino businesses thrived, helped in part by financial ties to home countries and by a customer base held captive by language barriers. Everywhere, it seemed, Mexican and Central American workers came to dominate low-wage work that had once gone to blacks—as waiters and busboys, as hotel maids and as bellmen—and made inroads in the construction trades that had long excluded black labor. Blacks began to grumble and feel threatened; they wondered if once again they were about to be passed over by those who’d just arrived.

As frustrated as blacks may get whenever they pass a construction site in a black neighborhood and see nothing but Mexican workers, I rarely hear them blame the workers themselves; usually they reserve their wrath for the contractors who hire them.

many blacks will express a grudging admiration for Latino immigrants—for their strong work ethic and commitment to family, their willingness to start at the bottom and make the most of what little they have.

(the Spanish-language Univision now boasts the highest-rated newscast in Chicago).

By the early nineties, Indonesia was considered an “Asian tiger,” the next great success story of a globalizing world. Even the darker aspects of Indonesian life—its politics and human rights record—showed signs of improvement.

perhaps I am worried about what I will find there—that the land of my childhood will no longer match my memories. As much as the world has shrunk, with its direct flights and cell phone coverage and CNN and Internet cafés, Indonesia feels more distant now than it did thirty years ago. I fear it’s becoming a land of strangers.

Providence had charged America with the task of making a new world, not reforming the old; protected by an ocean and with the bounty of a continent, America could best serve the cause of freedom by concentrating on its own development, becoming a beacon of hope for other nations and people around the globe.

Of course, manifest destiny also meant bloody and violent conquest—of Native American tribes forcibly removed from their lands and of the Mexican army defending its territory. It was a conquest that, like slavery, contradicted America’s founding principles and tended to be justified in explicitly racist terms, a conquest that American mythology has always had difficulty fully absorbing but that other countries recognized for what it was—an exercise in raw power.

Chris liked this

security and international cooperation. Sixty years later, we can see the results of this massive postwar undertaking: a successful outcome to the Cold War, an avoidance of nuclear catastrophe, the effective end of conflict between the world’s great military powers, and an era of unprecedented economic growth at home and abroad. It’s a remarkable achievement, perhaps the Greatest Generation’s greatest gift to us after the victory over fascism. But like any system built by man, it had its flaws and contradictions; it could fall victim to the distortions of politics, the sins of hubris, the

...more

But perhaps the biggest casualty of that war was the bond of trust between the American people and their government—and between Americans themselves. As a consequence of a more aggressive press corps and the images of body bags flooding into living rooms, Americans began to realize that the best and the brightest in Washington didn’t always know what they were doing—and didn’t always tell the truth. Increasingly, many on the left voiced opposition not only to the Vietnam War but also to the broader aims of American foreign policy.

I didn’t understand why, for example, progressives should be less concerned about oppression behind the Iron Curtain than they were about brutality in Chile. I couldn’t be persuaded that U.S. multinationals and international terms of trade were single-handedly responsible for poverty around the world; nobody forced corrupt leaders in Third World countries to steal from their people.

I waited with anticipation for what I assumed would follow: the enunciation of a U.S. foreign policy for the twenty-first century, one that would not only adapt our military planning, intelligence operations, and homeland defenses to the threat of terrorist networks but build a new international consensus around the challenges of transnational threats. This new blueprint never arrived. Instead what we got was an assortment of outdated policies from eras gone by, dusted off, slapped together, and with new labels affixed. Reagan’s “Evil Empire” was now “the Axis of Evil.” Theodore Roosevelt’s

...more

as a member of the Peace Corps. Many of the lessons he had learned there needed to be applied to the military’s work in Iraq, he told me. He didn’t have anywhere near the number of Arabic-speakers needed to build trust with the local population. We needed to improve cultural sensitivity within U.S. forces, develop long-term relationships with local leaders, and couple security forces to reconstruction teams, so that Iraqis could see concrete benefits from U.S. efforts. All this would take time, he said, but he could already see changes for the better as the military adopted these practices

...more

“I asked him what he thought we needed to do to best deal with the situation.” “What did he say?” “Leave.”

I don’t presume to have this grand strategy in my hip pocket. But I know what I believe, and I’d suggest a few things that the American people should be able to agree on, starting points for a new consensus. To begin with, we should understand that any return to isolationism—or a foreign policy approach that denies the occasional need to deploy U.S. troops—will not work.

Of course, conservatives are just as misguided if they think we can simply eliminate “the evildoers” and then let the world fend for itself.

The growing threat, then, comes primarily from those parts of the world on the margins of the global economy where the international “rules of the road” have not taken hold—the realm of weak or failing states, arbitrary rule, corruption, and chronic violence;

our immediate safety can’t be held hostage to the desire for international consensus; if we have to go it alone, then the American people stand ready to pay any price and bear any burden to protect our country.

by engaging our allies, we give them joint ownership over the difficult, methodical, vital, and necessarily collaborative work of limiting the terrorists’ capacity to inflict harm.

us a lunch of borscht, vodka, potato stew, and a deeply troubling fish Jell-O mold.

pulled a few test tubes from the freezer, waving them around a foot from my face and saying something in Ukrainian. “That is anthrax,” the translator explained, pointing to the vial in the woman’s right hand. “That one,” he said, pointing to the one in the left hand, “is the plague.”

The director of the facility, a rotund, cheerful man who reminded me of a Chicago ward superintendent,

One of our team called me over and showed me a yellowing poster taped to the wall. It was a relic of the Afghan war, we were told: instructions on how to hide explosives in toys, to be left in villages and carried home by unsuspecting children. A testament, I thought, to the madness of men. A record of how empires destroy themselves.

As for countries like Somalia, Sierra Leone, or the Congo, well, they have barely any law whatsoever. There are times when considering the plight of Africa—the millions racked by AIDS, the constant droughts and famines, the dictatorships, the pervasive corruption, the brutality of twelve-year-old guerrillas who know nothing but war wielding machetes or AK-47s—I find myself plunged into cynicism and despair. Until I’m reminded that a mosquito net that prevents malaria cost three dollars; that a voluntary HIV testing program in Uganda has made substantial inroads in the rate of new infections at

...more

Chris liked this

for those who chafe at the prospect of working with our allies to solve the pressing global challenges we face, let me suggest at least one area where we can act unilaterally and improve our standing in the world—by perfecting our own democracy and leading by example.

I am not naive enough to believe that one episode in the wake of catastrophe can erase decades of mistrust. But it’s a start.

None of these amendments would transform the country, but I took satisfaction in knowing that each of them helped some people in a modest way or nudged the law in a direction that might prove to be more economical, more responsible, or more just.

had volunteered at school to make sure her children were behaving and that the teachers were doing what they were supposed to be doing.

his bloodlines scattered to the four winds,

What has kept a large swath of American families from falling out of the middle class has been Mom’s paycheck.

with big, hypnotic eyes that seemed to read the world the moment they opened.

Of course, it’s not possible for the federal government to guarantee each family a wonderful, healthy, semiretired mother-in-law who happens to live close by. But if we’re serious about family values, then we can put policies in place that make the juggling of work and parenting a little bit easier.

Chris liked this

Whatever the case may be, such decisions should be honored. If there’s one thing that social conservatives have been right about, it’s that our modern culture sometimes fails to fully appreciate the extraordinary emotional and financial contributions—the sacrifices and just plain hard work—of the stay-at-home mom. Where social conservatives have been wrong is in insisting that this traditional role is innate—the best or only model of motherhood. I want my daughters to have a choice as to what’s best for them and their families. Whether they will have such choices will depend not just on their

...more

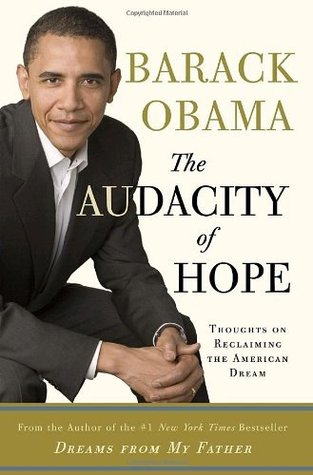

phrase that my pastor, Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr., had once used in a sermon. The audacity of hope. That was the best of the American spirit, I thought—having the audacity to believe despite all the evidence to the contrary that we could restore a sense of community to a nation torn by conflict; the gall to believe that despite personal setbacks, the loss of a job or an illness in the family or a childhood mired in poverty, we had some control—and therefore responsibility—over our own fate. It was that audacity, I thought, that joined us as one people.

Chris liked this

I thought about my mother and father and grandfather and what it might have been like for them to be in the audience. I thought about my grandmother in Hawaii, watching the convention on TV because her back was too deteriorated for her to travel. I thought about all the volunteers and supporters back in Illinois who had worked so hard on my behalf. Lord, let me tell their stories right, I said to myself.