More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

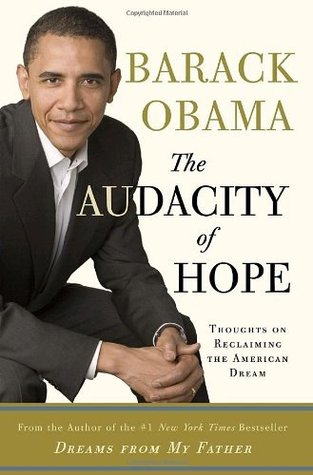

by

Barack Obama

Read between

March 6 - March 14, 2020

another tradition to politics, a tradition that stretched from the days of the country’s founding to the glory of the civil rights movement, a tradition based on the simple idea that we have a stake in one another, and that what binds us together is greater than what drives us apart, and that if enough people believe in the truth of that proposition and act on it, then we might not solve every problem, but we can get something meaningful done.

No blinding insights emerged from these months of conversation. If anything, what struck me was just how modest people’s hopes were, and how much of what they believed seemed to hold constant across race, region, religion, and class. Most of them thought that anybody willing to work should be able to find a job that paid a living wage. They figured that people shouldn’t have to file for bankruptcy because they got sick. They believed that every child should have a genuinely good education—that it shouldn’t just be a bunch of talk—and that those same children should be able to go to college

...more

Still, there was no point in denying my almost spooky good fortune. I was an outlier, a freak; to political insiders, my victory proved nothing.

When Democrats rush up to me at events and insist that we live in the worst of political times, that a creeping fascism is closing its grip around our throats, I may mention the internment of Japanese Americans under FDR, the Alien and Sedition Acts under John Adams, or a hundred years of lynching under several dozen administrations as having been possibly worse, and suggest we all take a deep breath.

When people at dinner parties ask me how I can possibly operate in the current political environment, with all the negative campaigning and personal attacks, I may mention Nelson Mandela, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, or some guy in a Chinese or Egyptian prison somewhere. In truth, being called names is not such a bad deal.

It’s not simply that a gap exists between our professed ideals as a nation and the reality we witness every day. In one form or another, that gap has existed since America’s birth. Wars have been fought, laws passed, systems reformed, unions organized, and protests staged to bring promise and practice into closer alignment. No, what’s troubling is the gap between the magnitude of our challenges and the smallness of our politics—the ease with which we are distracted by the petty and trivial, our chronic avoidance of tough decisions, our seeming inability to build a working consensus to tackle

...more

it was Nixon, after all, who initiated the first federal affirmative action programs and signed the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration into law.

Whatever the explanation, after Reagan the lines between Republican and Democrat, liberal and conservative, would be drawn in more sharply ideological terms. This was true, of course, for the hot-button issues of affirmative action, crime, welfare, abortion, and school prayer, all of which were extensions of earlier battles. But it was also now true for every other issue, large or small, domestic or foreign, all of which were reduced to a menu of either-or, for-or-against, sound-bite-ready choices. No longer was economic policy a matter of weighing trade-offs between competing goals of

...more

Unless political leaders are open to new ideas and not just new packaging, we won’t change enough hearts and minds to initiate a serious energy policy or tame the deficit. We won’t have the popular support to craft a foreign policy that meets the challenges of globalization or terrorism without resorting to isolationism or eroding civil liberties. We won’t have a mandate to overhaul America’s broken health-care system. And we won’t have the broad political support or the effective strategies needed to lift large numbers of our fellow citizens out of poverty.

Maybe the critics are right. Maybe there’s no escaping our great political divide, an endless clash of armies, and any attempts to alter the rules of engagement are futile. Or maybe the trivialization of politics has reached a point of no return, so that most people see it as just one more diversion, a sport, with politicians our paunch-bellied gladiators and those who bother to pay attention just fans on the sidelines: We paint our faces red or blue and cheer our side and boo their side, and if it takes a late hit or cheap shot to beat the other team, so be it, for winning is all that

...more

I imagine they are waiting for a politics with the maturity to balance idealism and realism, to distinguish between what can and cannot be compromised, to admit the possibility that the other side might sometimes have a point. They don’t always understand the arguments between right and left, conservative and liberal, but they recognize the difference between dogma and common sense, responsibility and irresponsibility, between those things that last and those that are fleeting. They are out there, waiting for Republicans and Democrats to catch up with them.

Moreover, most people who serve in Washington have been trained either as lawyers or as political operatives—professions that tend to place a premium on winning arguments rather than solving problems. I can see how, after a certain amount of time in the capital, it becomes tempting to assume that those who disagree with you have fundamentally different values—indeed, that they are motivated by bad faith, and perhaps are bad people.

In a country as diverse as ours, there will always be passionate arguments about how we draw the line when it comes to government action. That is how our democracy works. But our democracy might work a bit better if we recognized that all of us possess values that are worthy of respect: if liberals at least acknowledged that the recreational hunter feels the same way about his gun as they feel about their library books, and if conservatives recognized that most women feel as protective of their right to reproductive freedom as evangelicals do of their right to worship.

I listened to a Republican colleague work himself into a lather over a proposed plan to provide school breakfasts to preschoolers. Such a plan, he insisted, would crush their spirit of self-reliance. I had to point out that not too many five-year-olds I knew were self-reliant, but children who spent their formative years too hungry to learn could very well end up being charges of the state.

Values are faithfully applied to the facts before us, while ideology overrides whatever facts call theory into question.

In 1980, the average CEO made forty-two times what an average hourly worker took home. By 2005, the ratio was 262 to 1. Conservative outlets like the Wall Street Journal editorial page try to justify outlandish salaries and stock options as necessary to attract top talent, and suggest that the economy actually performs better when America’s corporate leaders are fat and happy. But the explosion in CEO pay has had little to do with improved performance. In fact, some of the country’s most highly compensated CEOs over the past decade have presided over huge drops in earnings, losses in

...more

And yet I find myself returning again and again to my mother’s simple principle—“How would that make you feel?”—as a guidepost for my politics.

I believe a stronger sense of empathy would tilt the balance of our current politics in favor of those people who are struggling in this society. After all, if they are like us, then their struggles are our own. If we fail to help, we diminish ourselves.

That’s what empathy does—it calls us all to task, the conservative and the liberal, the powerful and the powerless, the oppressed and the oppressor. We are all shaken out of our complacency. We are all forced beyond our limited vision. No one is exempt from the call to find common ground.

Listening to Senator Byrd speak, I felt with full force all the essential contradictions of me in this new place, with its marble busts, its arcane traditions, its memories and its ghosts. I pondered the fact that, according to his own autobiography, Senator Byrd had received his first taste of leadership in his early twenties, as a member of the Raleigh County Ku Klux Klan, an association that he had long disavowed, an error he attributed—no doubt correctly—to the time and place in which he’d been raised, but which continued to surface as an issue throughout his career.

Stamped into the very fiber of the Senate, within its genetic code, was the same contest between power and principle that characterized America as a whole, a lasting expression of that great debate among a few brilliant, flawed men that had concluded with the creation of a form of government unique in its genius—yet blind to the whip and the chain.

Gaining control of the courts generally and the Supreme Court in particular had become the holy grail for a generation of conservative activists—and not just, they insisted, because they viewed the courts as the last bastion of pro-abortion, pro-affirmative-action, pro-homosexual, pro-criminal, pro-regulation, anti-religious liberal elitism. According to these activists, liberal judges had placed themselves above the law, basing their opinions not on the Constitution but on their own whims and desired results, finding rights to abortion or sodomy that did not exist in the text, subverting the

...more

But when the Democrats lost their Senate majority in 2002, they had only one arrow left in their quiver, a strategy that could be summed up in one word, the battle cry around which the Democratic faithful now rallied: Filibuster!

The only way to break a filibuster is for three-fifths of the Senate to invoke something called cloture—that is, the cessation of debate. Effectively this means that every action pending before the Senate—every bill, resolution, or nomination—needs the support of sixty senators rather than a simple majority.

Sometimes I imagined my work to be not so different from the work of the theology professors who taught across campus—for, as I suspect was true for those teaching Scripture, I found that my students often felt they knew the Constitution without having really read it. They were accustomed to plucking out phrases that they’d heard and using them to bolster their immediate arguments, or ignoring passages that seemed to contradict their views.

Conservative or liberal, we are all constitutionalists.

Ultimately, though, I have to side with Justice Breyer’s view of the Constitution—that it is not a static but rather a living document, and must be read in the context of an ever-changing world.

Because power in our government is so diffuse, the process of making law in America compels us to entertain the possibility that we are not always right and to sometimes change our minds; it challenges us to examine our motives and our interests constantly, and suggests that both our individual and collective judgments are at once legitimate and highly fallible.

The rejection of absolutism implicit in our constitutional structure may sometimes make our politics seem unprincipled. But for most of our history it has encouraged the very process of information gathering, analysis, and argument that allows us to make better, if not perfect, choices, not only about the means to our ends but also about the ends themselves.

Still, I know that as a consequence of my fund-raising I became more like the wealthy donors I met, in the very particular sense that I spent more and more of my time above the fray, outside the world of immediate hunger, disappointment, fear, irrationality, and frequent hardship of the other 99 percent of the population—that is, the people that I’d entered public life to serve.

I found myself hedging on such questions, writing in the margins, explaining the difficult policy choices involved. My staff would shake their heads. Get one answer wrong, they explained, and the endorsement, the workers, and the mailing list would all go to the other guy. Get them all right, I thought, and you have just locked yourself into the pattern of reflexive, partisan jousting that you have promised to help end.

It’s hard to deny that political civility has declined in the past decade, and that the parties differ sharply on major policy issues. But at least some of the decline in civility arises from the fact that, from the press’s perspective, civility is boring. Your quote doesn’t run if you say, “I see the other guy’s point of view” or “The issue’s really complicated.” Go on the attack, though, and you can barely fight off the cameras.

Apparently, Moynihan was in a heated argument with one of his colleagues over an issue, and the other senator, sensing he was on the losing side of the argument, blurted out: “Well, you may disagree with me, Pat, but I’m entitled to my own opinion.” To which Moynihan frostily replied, “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you are not entitled to your own facts.”

Moynihan’s assertion no longer holds. We have no authoritative figure, no Walter Cronkite or Edward R. Murrow whom we all listen to and trust to sort out contradictory claims. Instead, the media is splintered into a thousand fragments, each with its own version of reality, each claiming the loyalty of a splintered nation. Depending on your viewing preferences, global climate change is or is not dangerously accelerating; the budget deficit is going down or going up.

On the drive back to Chicago, I tried to imagine Tim’s desperation: no job, an ailing son, his savings running out. Those were the stories you missed on a private jet at forty thousand feet.

The result has been the emergence of what some call a “winner-take-all” economy, in which a rising tide doesn’t necessarily lift all boats. Over the past decade, we’ve seen strong economic growth but anemic job growth; big leaps in productivity but flatlining wages; hefty corporate profits, but a shrinking share of those profits going to workers. For those like Larry Page and Sergey Brin, for those with unique skills and talents and for the knowledge workers—the engineers, lawyers, consultants, and marketers—who facilitate their work, the potential rewards of a global marketplace have never

...more

For the most part, though, the Republican economic agenda under President Bush has been devoted to tax cuts, reduced regulation, the privatization of government services—and more tax cuts.

I’m confident that we have the talent and the resources to create a better future, a future in which the economy grows and prosperity is shared. What’s preventing us from shaping that future isn’t the absence of good ideas. It’s the absence of a national commitment to take the tough steps necessary to make America more competitive—and the absence of a new consensus around the appropriate role of government in the marketplace.

Throughout our history, education has been at the heart of a bargain this nation makes with its citizens: If you work hard and take responsibility, you’ll have a chance for a better life. And in a world where knowledge determines value in the job market, where a child in Los Angeles has to compete not just with a child in Boston but also with millions of children in Bangalore and Beijing, too many of America’s schools are not holding up their end of the bargain.

America now has one of the highest high school dropout rates in the industrialized world. By their senior year, American high school students score lower on math and science tests than most of their foreign peers. Half of all teenagers can’t understand basic fractions, half of all nine-year-olds can’t perform basic multiplication or division, and although more American students than ever are taking college entrance exams, only 22 percent are prepared to take college-level classes in English, math, and science. I don’t believe government alone can turn these statistics around. Parents have the

...more

Recent studies show that the single most important factor in determining a student’s achievement isn’t the color of his skin or where he comes from, but who the child’s teacher is. Unfortunately, too many of our schools depend on inexperienced teachers with little training in the subjects they’re teaching, and too often those teachers are concentrated in already struggling schools.

Over the last five years, the average tuition and fees at four-year public colleges, adjusted for inflation, have risen 40 percent. To absorb these costs, students have been taking on ever-increasing debt levels, which discourages many undergraduates from pursuing careers in less lucrative fields like teaching. And an estimated two hundred thousand college-qualified students each year choose to forgo college altogether because they can’t figure out how to pay the bills.

Over the last three decades federal funding for the physical, mathematical, and engineering sciences has declined as a percentage of GDP—just at the time when other countries are substantially increasing their own R & D budgets. And as Dr. Langer points out, our declining support for basic research has a direct impact on the number of young people going into math, science, and engineering—which helps explain why China is graduating eight times as many engineers as the United States every year.

Countries like Brazil have already done this. Over the last thirty years, Brazil has used a mix of regulation and direct government investment to develop a highly efficient biofuel industry; 70 percent of its new vehicles now run on sugar-based ethanol instead of gasoline.

And FDR recognized that we would all be more likely to take risks in our lives—to change jobs or start new businesses or welcome competition from other countries—if we knew that we would have some measure of protection should we fail.

The wages of the average American worker have barely kept pace with inflation over the past two decades.

In other words, the Ownership Society doesn’t even try to spread the risks and rewards of the new economy among all Americans. Instead, it simply magnifies the uneven risks and rewards of today’s winner-take-all economy. If you are healthy or wealthy or just plain lucky, then you will become more so. If you are poor or sick or catch a bad break, you will have nobody to look to for help. That’s not a recipe for sustained economic growth or the maintenance of a strong American middle class. It’s certainly not a recipe for social cohesion. It runs counter to those values that say we have a stake

...more

“I’ll tell you, not very many,” he said. “They have this idea that it’s ‘their money’ and they deserve to keep every penny of it. What they don’t factor in is all the public investment that lets us live the way we do. Take me as an example. I happen to have a talent for allocating capital. But my ability to use that talent is completely dependent on the society I was born into. If I’d been born into a tribe of hunters, this talent of mine would be pretty worthless. I can’t run very fast. I’m not particularly strong. I’d probably end up as some wild animal’s dinner. “But I was lucky enough to

...more

The single biggest gap in party affiliation among white Americans is not between men and women, or between those who reside in so-called red states and those who reside in blue states, but between those who attend church regularly and those who don’t.

This isn’t to say that she provided me with no religious instruction. In her mind, a working knowledge of the world’s great religions was a necessary part of any well-rounded education. In our household the Bible, the Koran, and the Bhagavad Gita sat on the shelf alongside books of Greek and Norse and African mythology. On Easter or Christmas Day my mother might drag me to church, just as she dragged me to the Buddhist temple, the Chinese New Year celebration, the Shinto shrine, and ancient Hawaiian burial sites. But I was made to understand that such religious samplings required no sustained

...more