More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In 1958 economist John Kenneth Galbraith (soon to become an advisor to JFK) in The Affluent Society had described the post–World War II United States as flourishing in the private sphere but impoverished in the public sector, with inadequate social and physical infrastructure and persistent income disparities.

Michael Harrington’s The Other America: Poverty in the United States (published in March 1962) helped to start the Great Society. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (published in September 1962) generated a half century of environmentalism. James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (published in January 1963) eloquently implored Americans to transcend “the Negro Problem” and foreshadowed the grim racial strains of the next half century.45 Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (published in February 1963) inspired a new feminism

Ronald Inglehart argued that the material affluence of the 1960s had freed the younger generation to turn to “self-actualization.” “Man does not live by bread alone, especially if he has plenty of bread” was the adroit way Inglehart summarized his thesis.47 And it was a short step from self-actualization to narcissism.

Bob Dylan, whose roots were in acoustic guitar and folk music, as exemplified by his early hits, “Blowin’ in the Wind” (1963) and “The Times They Are A’Changin’ ” (1964).

But in July 1965 at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan’s famous mid-concert turn from acoustic anthems to electric rock aroused strong (and mostly negative) reactions,

Like Dylan, the Beatles in the early 1960s sang in harmony about togetherness—“I Want to Hold Your Hand” (1963); “All You Need Is Love” (1967); “With a Little Help from My Friends” (1967). But already by 1966 they had become more attuned to isolation and alienation, when they wrote of Eleanor Rigby and Father McKenzie: “All the lonely people / Where do they all come from?”

The idea of self-love as a virtue, not a vice, became a New Age “thing” in the late 1960s and 1970s. The refrain “learning to love yourself… is the greatest love of all” was originally recorded in a song for the 1977 Muhammad Ali biopic The Greatest. (In later years the phrase would reappear in smash hits by Whitney Houston and Olivia

In principle and increasingly in practice, birth control separated sex from marriage. The change in sexual mores came with breathtaking speed. The fraction of all Americans who believed that premarital sex was “not wrong” doubled in barely four years from 24 percent in 1969 to 47 percent in 1973.

“Alienation,” “anomie,” “estrangement,” and “malaise” all soared as Ngram buzzwords during the Long Sixties. The mood was encapsulated in 1979 by a nationally televised address by President Jimmy Carter—summarizing virtually all of the events and trends that we have described in this section—a talk that he titled a “Crisis of Confidence” but that was quickly and appropriately dubbed “the malaise speech.”

Paul Harris’s Rotary Club was one of hundreds of similar organizations and associations started during the Progressive Era, each an outgrowth of a wider cultural turn away from atomization and individualism and toward “association” and communitarianism.

Henry George was a political philosopher who had published his first book, Progress and Poverty, in 1879, to enormous commercial success. During the 1890s, its sales exceeded all other books except the Bible, and it had an enormous influence on Progressives—a great many of whom credited an encounter with George’s ideas with reorienting their lives toward social and political reform. He argued vehemently for mechanisms to control the astronomical wealth of monopolistic businesses, and their influence on destructive boom-bust cycles in the economy.

As all of these stories illustrate, the Progressive movement was, first and foremost, a moral awakening. Facilitated by the muckrakers’ revelations about a society, economy, and government run amok—and urged on by the Social Gospelers’ denunciation of social Darwinism and laissez-faire economics—Americans from all walks of life began to repudiate the self-centered, hyper-individualist creed of the Gilded Age.

But, as political commentator E. J. Dionne has written, “Democracy is a long game. It involves pressuring those who resist reform… and offering proposals future electorates can eventually endorse.”

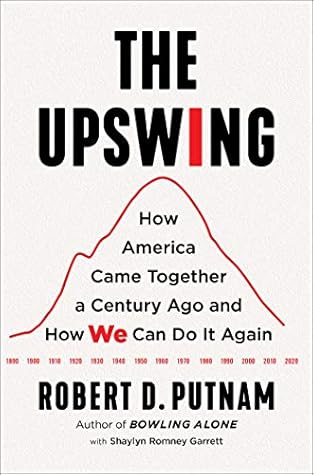

By employing those tools to uncover the I-we-I curve, we hope that this book will be an important contribution to bridging today’s generation gap and creating a more fruitful national conversation, which will be a vital component of rebuilding a robust American “we.”

As we pointed out in Chapter 3, the issues that rose to the national agenda during the Progressive Era bear a striking resemblance to those being debated today: universal health insurance; safety nets for the elderly, the jobless, and the disabled; progressive income and estate taxation; environmental regulation; labor reform; curtailing the overreach of big business monopolies; gender equality; and campaign finance reform.

Progressive reformers quickly learned that in order to succeed they would have to compromise—to find a way to put private property, personal liberty, and economic growth on more equal footing with communitarian ideals and the protection of the weak and vulnerable, and to work within existing systems to bring about change.27

If we abandon equality, we lose the single bond that makes us a community, that makes us a people with the capacity to be free collectively and individually in the first place.31 Like Allen, we reject the view that more freedom necessarily entails less equality and community, believing instead with Alexis de Tocqueville that individualism “rightly understood” is perfectly compatible with community and equality.32

This task will not be an easy one, and nothing less than the success of the American experiment is at stake. But as we look to an uncertain future we must keep in mind what is perhaps the greatest lesson of America’s I-we-I century: As Theodore Roosevelt put it, “the fundamental rule of our national life—the rule which underlies all others—is that, on the whole, and in the long run, we shall go up or down together.”

Harvard University served as the primary host for this research project, as it has for our previous work, and we are especially grateful to the Harvard Kennedy School and its dean, Douglas Elmendorf.

That last caveat also applies to a number of friends who were big-hearted enough to offer advice on the entire manuscript, including Xavier de Souza Briggs, David Brooks, Peter Davis, Angus Deaton,

I am also indebted to David Brooks and his team at the Aspen Institute’s Weave: The Social Fabric Project for giving me the opportunity to travel the country during my writing of this book to see firsthand the challenges facing American communities today as well as the myriad grassroots solutions well underway in every corner of our nation. I’d also like to thank David for mentoring me as a writer, helping me rekindle my passion for storytelling, and giving me courage to find my own voice.

Above all, in this context I want to recognize my lifelong intellectual debt to Robert Axelrod. Bob and I have been best friends since our first day of graduate school at Yale in the fall of 1964.

the Kresge Foundation provided the sole support for this project for four years, not once questioning me, even about missed deadlines. I am deeply grateful to Rip for his trust and encouragement on The Upswing, and my main hope is that this book will not disappoint him.

SHAYLYN ROMNEY GARRETT is a writer and award-winning social entrepreneur. She is a Founding Contributor to “Weave: The Social Fabric Project,” an Aspen Institute initiative.

CHAPTER 1: WHAT’S PAST IS PROLOGUE 1 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Cambridge, MA: Sever & Francis, 1863), chap. 8. Several chapters later he warned of the danger to democracy if the collective interest became overwhelmed by an emphasis on individual rights.

“Gilded Age” refers to the period 1870–1900 and “Progressive Era” to 1900–1915. Like

The standard (and more nuanced) account of American technological change and economic progress is Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U. S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Angus Deaton, The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013) and Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth have offered abundant evidence for the post-1970 falloff in the long-term annual growth rate.

Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).

See, for example, Christopher H. Achen, “Mass Political Attitudes and Survey Response,” American Political Science Review 69, no. 4 (December 1975): 1218–31, doi:10.2307/1955282; Duane F. Alwin and Jon A. Krosnick, “Aging, Cohorts, and the Stability of Sociopolitical Orientations Over the Life Span,” American Journal of Sociology 97, no. 1 (July 1991): 169–95, doi:10.1086/229744; David O. Sears and Carolyn L. Funk, “Evidence of the Long-Term Persistence of Adults’ Political Predispositions,” The Journal of Politics 61, no. 1 (1999): 1–28, doi:10.2307/2647773; and Gregory Markus, “Stability and

...more