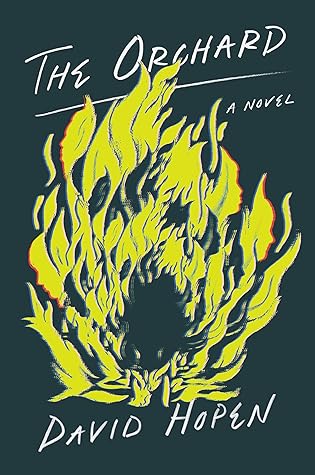

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Soon, I was biking over after school and perching myself in the corner, where the librarian, Mrs. Sanders, with her cherubic-white hair and feline eyes, had grown accustomed to leaving me stacks of “mandatory” books. “Nobody reads these,” she’d say. Night. Death of a Salesman. “You’re going to make up for everyone else.”

What was saddening was the realization that, in time, we stand in emptied houses to learn we’ve never made a mark.

I was a stranger in my previous existence, but one who understood that the rules governing each detail of life—how to marry, how to think, how to tie my shoes—were prescribed, always, by an aspirational morality.

“No man chooses evil because it is evil; he only mistakes it for happiness, the good he seeks.” (Mary Wollstonecraft)

I was conscious suddenly of how alone I was, how alone I’d always been.

I had prepared to embrace this unease. Finally, I told myself, I had before me the opportunity I wanted. I could look upon unfamiliar faces and pretend to be anyone. I could be extroverted, easygoing, a tabula rasa. Yet when the moment came I failed, as I knew I would, to see myself beyond what I’d been until now: solitary, a formless presence in a foreign world. I accepted this in the way one accepts scientific fact—unfeelingly, without any resentment toward a truth that, though previously unrealized, had always existed.

Happiness shall elude you, and yet you shall pursue it. We never reach permanent happiness, but we move steadily after its shadow, both physically and spiritually. We creep closer and closer toward God, each time halving the distance, but what we stand before is only an approximation. We move to new places, we visualize new achievements, but the yearning remains, because a life devoid of longing is not, in the eyes of the Talmud, a life fit for a human.

“I guess the anti-self is something almost, I don’t know, aspirational. You’re dissatisfied with the current image of yourself, which feels maybe inadequate or too nebulous, and so as a remedy you picture another self, a superior life, one attached to excellence or virtue or, in this case, to art.”

“Do be careful who you follow into the dark.”

Do the gods light this fire in our hearts Or does each man’s mad desire become his god? —Virgil, Aeneid

“That’s the whole fun, isn’t it?” Rabbi Bloom said. “Finding out where we belong?”

Keats describes two rooms in the “large Mansion” of human life: the antechamber, where we suppress consciousness, and the Chamber of Maiden-Thought, where we become intoxicated by beauty, only to discover heartbreak. I was now, at last, experiencing whatever darkness follows fleeting light.

“Because the Judaism you teach here relegates the individual to an afterthought. It cares little about how you feel. It makes you fall in line and sacrifice everything and wait patiently for the next world, where you can finally earn it all back, where all that suffering actually amounts to something. But does it give a shit about the self? Does it have anything to say when you’re alone? When you’re betrayed? When your mother dies?”

“It’s like what Yeats teaches and Nietzsche teaches and whoever else teaches. What Shir HaShirim teaches: Shkhora ani venavah. I am dark, but beautiful.”

When boat shows up, get fuck in, don’t ask questions.”

“But that’s what happens, isn’t it? All of us, everybody, we fool ourselves into believing someone loves us the way we love them.”

I wondered whether my ability to overlook such occasional bursts of casual cruelty indicated weakness on my part, a lack of self-esteem, perhaps, some depraved willingness to put myself at her mercy.

Who alone suffers, suffers most i’ th’ mind, Leaving free things and happy shows behind. —Shakespeare, King Lear