More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

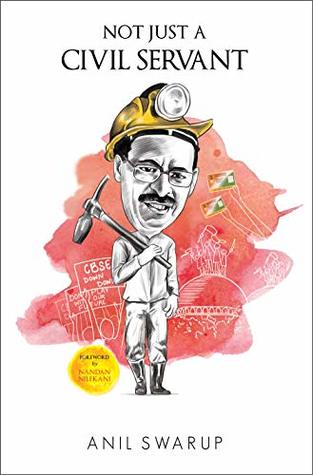

This book is an attempt to share some of my experiences in serving the poorest of the poor and the richest of the rich. I was blessed to have come across some outstanding officers and individuals who inspired me to remain committed and on track because they had delivered.

The then UPA Government was gracious enough to appoint me as Cabinet Minister. In the first few weeks, I had realised that just having a rank did not get you very far in navigating the byzantine corridors of power in India’s capital. I had clearly bitten off a lot, having set myself the task of giving over a billion Indian residents a unique identity number.

While conversing with my writer and intellectual friend Gurcharan Das, I heard about the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) project and of course, about the leader of it— IAS officer Mr Anil Swarup. I was intrigued and decided to meet Anil.

Anil was the first to implement smartcards for such a huge project. He had cobbled together a motley coalition of supporters, from the World Bank to the German development agency, GTZ. He was spearheading a ‘health’ project, being in Labour & Employment, not from the Ministry of Health.

Anil did not follow this guidebook. Controlling the turmoil of UP in the initial years as an officer to Coal Ministry to Secretary, School Education in the Central Government, Anil has beautifully juggled passion, risk, challenges and quick decisions to make a difference and leave a mark. He has been ever willing to do ‘start-ups’ like RSBY and the Project Management Group (PMG).

Moreover, his visualisation of the impact of technology in bringing development and transparency has helped him to bring in many innovations, from biometric authentication in RSBY to the on-line portal in the Project Management Group to e-auctions in coal.

Over the last few years, decision making in the Indian Government has become crippled, thanks to the overhang of the 5C...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I was then to join the Muir (Amarnath Jha) Hostel, Allahabad University. It was considered a breeding ground for civil servants.

My articulation, verbal or written, was poor. As I made conscious efforts to improve, I faced ridicule by my peers. However, I was focussed and carried on.

When my name was announced the following day, the audience started chanting— ‘the singer’! However, the debater in me persisted and I went on to win the first prize. After that, there was no looking back.

The focus during the second attempt was to pin down the answers within a stipulated time. This made all the difference. I made it to the IAS in the second attempt.

As they say, it takes all types to make this world… it was true of the bureaucrats as well.

The 1990 Ram Janam Bhoomi issue appeared as a test for all those who were in charge of districts. There was communal tension all around, with more than half of the districts under curfew. Lakhimpur-Kheri took pride in keeping the tension under check without imposing curfew. This was achieved at a considerable cost.

On several occasions one’s oratorical skills were put to use while convincing the youth that beyond ‘MANDAL’ there was a future. This argument did not cut much ice to begin with, but one had very less options at one’s command.

Those that have perfected the art of managing the politicians have had longer tenures. However, all said and done, despite the erosion in the institution of the District Magistrate, it still commands a lot of authority and one’s conventional managerial skills are not really put to test.

Now that tenures are extremely short, he can get away with it as well. However, a committed District Magistrate can do a lot, if he so desires, by motivating the men under him in the redressal of grievances, in fostering development and in toning up the revenue machinery.

Though I was new to the assignment and his political rallies were none of my business, I offered some unsolicited advice. I told him that it would not be appropriate to cancel the rallies at the last moment. With my recent experience as a DM, I also told him that a lot of preparatory work goes into rallies and there would be a lot of anticipation on the ground. The CM, apparently, did not like my intervention, at least in the beginning.

I politely replied to the CM that my suggestion was my professional view; and it was up to him to take the final call.

The CM finally broke the silence. “Anilji, aap theek keh rahe hain.” (Anil, you are right.) He agreed that it would not be appropriate to cancel the scheduled rallies.

Post-independence, this was whittled substantially but the respect was still there. He was still the head of District Administration and the formal representative of the Government at the district level. On contrary to this, the office of Executive Director, Udyog Bandhu was not so authoritative. Udyog Bandhu was set up to promote industrialisation in the state of Uttar Pradesh. As against an uncertain tenure and almost an unquestioned authority, I was catapulted into Udyog Bandhu

In fact, my role underwent a metamorphosis. It was now that of a facilitator. Whereas in my position as a District Magistrate it was the government machinery which was instrumental in solving the problems of an average person, I was now attempting to remove the bottlenecks created because of government

The assistance in this task was not provided by hard-boiled bureaucrats but by professionals. What came handy was the experience to appreciate and analyse problems. There was no longer the queue of servile ‘Mulaquatis’ awaiting ‘darshan’ for small favours as was a common sight in the district.

However, one’s preoccupation with law & order hardly spared time for any such creative activities. It was not so in the new dispensation which not only provided time but adequate professional assistance and scope to indulge in creativity.

The transformation was not an easy one as the attributes required to work as a District Magistrate and those as a facilitator were different. A facilitator had to go out and meet people and convince them about the good things in a state.

conviction that a lot could still be done both with the politician and with the bureaucracy. The dead end was still far off. The clear stream of reason had still ‘not lost its way in the dreary desert sand of dead habit’.